[ad_1]

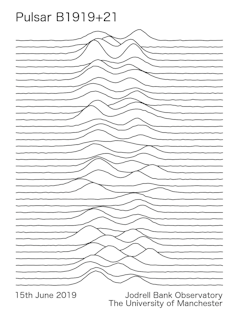

Forty years ago, British rock band Joy Division released their first studio album, "Unknown Pleasures". The cover page contains no words, there is only one black and white graphical data, now iconic, containing 80 wavy lines. To mark the anniversary of the album, we recorded a signal of the same object in space with a radio telescope in the observatory of Jodrell Bank, just 23 km from the studio Strawberry where the Recording has been recorded.

Peter Saville – graphic designer and co-founder of Factory Records – designed the album cover from an image spotted by group member Bernard Sumner in an encyclopedia. The photo itself can be attributed to the work of Harold Craft, a postgraduate student, who published the picture in his PhD thesis in 1970. But what exactly are the sinuous lines?

Jodrell Bank Center for Astrophysics, University of Manchester, Author provided

Unknown treasures in space

What we see in this enigmatic image is the signal produced by a pulsar called B1919 + 21, the first pulsar ever discovered. A pulsar is formed during the violent death of a star many times more massive than our sun. These stars extinguish themselves with an explosion called "supernova explosion", during which the exploding star nucleus is compressed into an almost perfect sphere whose radius does not exceed 10 km. What is formed is called a neutron star.

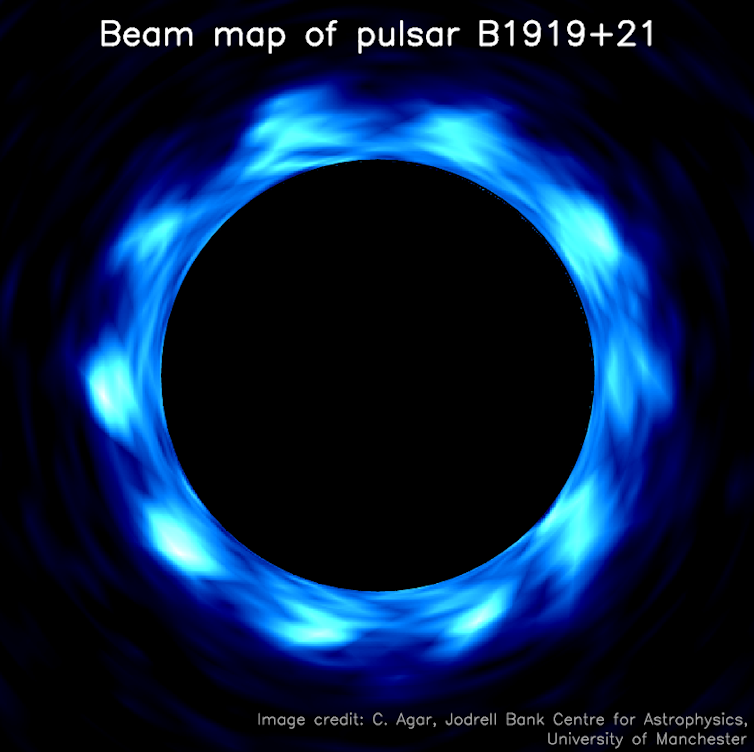

This stellar remainder, even more massive than our sun, is so dense that the atoms of the original star can not maintain their structure. They disintegrate and form smaller particles called neutrons, which form a vast ocean under the crust of the star. Pulsars are rapidly rotating neutron stars that can be observed from Earth. Thanks to their rotation and a magnetic field one trillion times stronger than Earth's, the magnetic poles north and south of these super magnets shine like a beacon. After traveling for hundreds of years, B1919 + 21 lightning strikes the Earth every 1.34 seconds.

Pulsar flashes are particularly bright at radio wavelengths, so their signals can be recorded using radio telescopes. A radio telescope works like a radio in your car: its antenna focuses the radio waves of space on a point where they can be detected and converted into an electrical signal, which can then be converted to sound. We used the Mark II radio telescope from the Jodrell Bank Observatory of the University of Manchester for our recording.

Mike Peel / Jodrell Bank Center for Astrophysics, University of Manchester, CC BY-SA

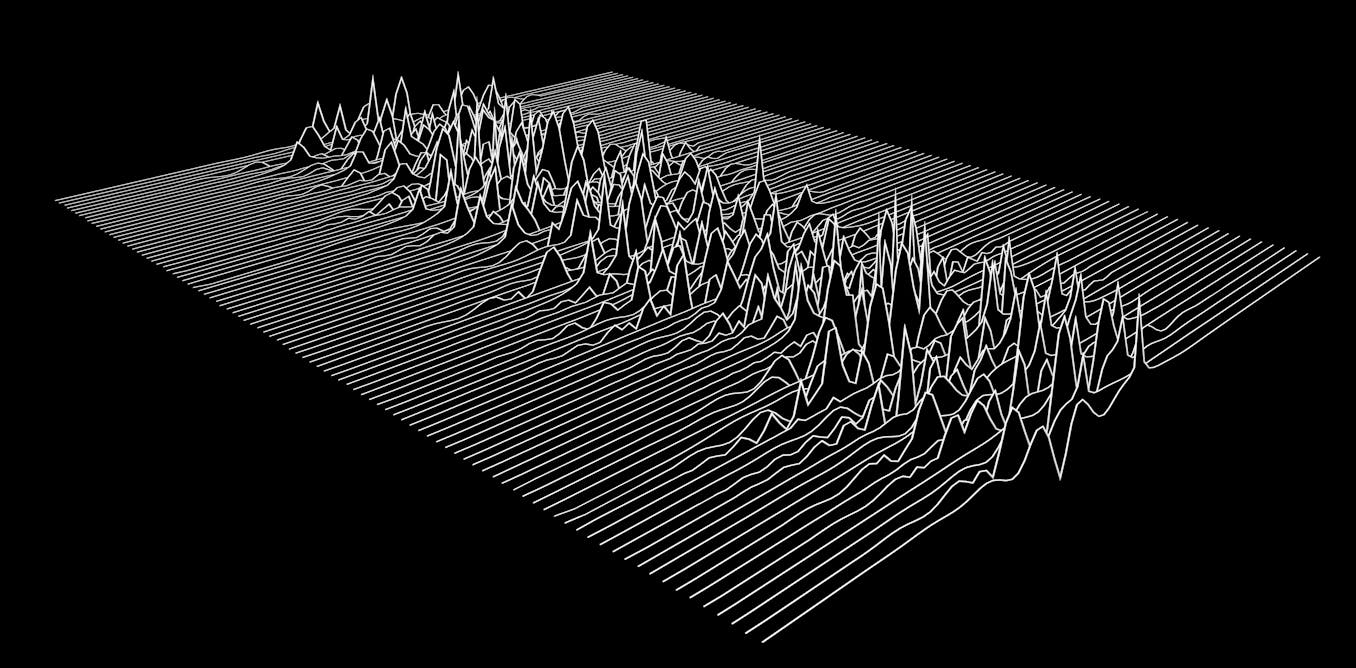

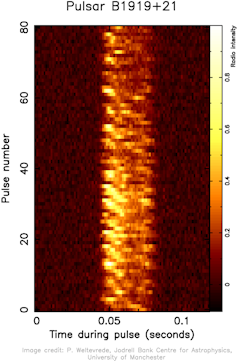

The cover of the album shows 80 wavy lines that correspond to 80 flashes of radio waves of B1919 + 21, the neutron star having made 80 laps in 107 seconds. Unlike lighthouses on Earth, each flash is unique. Some flashes are clear – these are indicated in the image by their large spikes – and some are dark.

The shape of the impulses changes constantly. At first glance, they seem irregular and chaotic, but our new imagery reveals some order in chaos. This is the same number of pulses from the same pulsar and observed at the same frequency as the album cover diagram, but in the illustration below, a diagonal pattern of bands appears.

Jodrell Bank Center for Astrophysics, University of Manchester, Author provided

When the original signal was recorded, it was not known why some pulsars had this type of pattern. We now think that radio waves are produced by particles that move away from the neutron star at a speed close to that of light. The particles are created by electrical discharges between the ionized gas surrounding these objects and the surface of the star itself. Thus, the radio waves on the cover of the album and in our new imagery are mainly caused by lightning in space, observed many light-years away.

A "weather map" can help visualize the vast lightning systems that circulate the magnetic poles of pulsars. The pattern of their lightning changes continuously and the shape of the pulses observed appears somewhat irregular – but observation over a longer period allows a pattern to emerge.

Jodrell Bank Center for Astrophysics, University of Manchester, Author provided

Four decades after the release of the album Unknown Pleasures, we now understand a lot better what these wavy lines mean on its cover. But there are still many questions about these enigmatic objects, which are in many ways the most extreme creation of nature. What has remained true for all these years is that pulsar recordings push us to explore the limits of our understanding of the laws of physics.

[ad_2]

Source link