[ad_1]

"I I WANT JUST end the price spree, "says Sonia Valverde, a mother of three, in a supermarket in Buenos Aires. She cites a government sticker announcing the new price control, which has frozen the price of 64 products, including bags of milk. The only difficulty is that there is no bag left on the shelf.

Ending the madness of prices in Argentina was Mauricio Macri's main mission when he took over the presidency in 2015. He lifted the exchange controls imposed by his populist predecessor, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, and began reducing energy subsidies. He gave the central bank an inflation target and let the statisticians measure it honestly. And he eased price controls that Fernandez had imposed on hundreds of items, including soap and chicken.

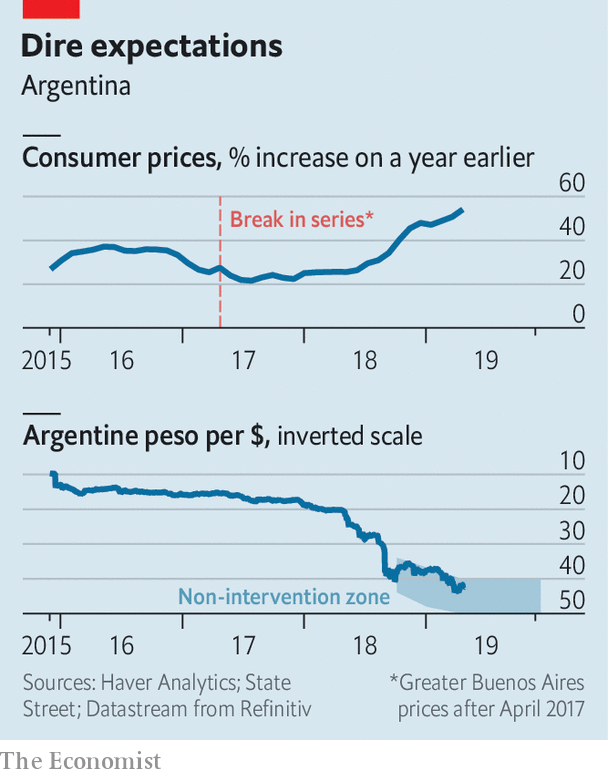

But the infuriating prices of Argentina are not tamed. When inflation fell more slowly than expected, the government eased the central bank's inflation target at the end of 2017, undermining its credibility. As US Treasury yields rose months later, the peso fell and inflation soared. Argentina has embraced the IMF and abandoned its goal of inflation in favor of a more direct goal of limiting the money supply. Even after the central bank promised to freeze the amount of money until the end of this year, the peso faltered and annual inflation soared to nearly 55% in March (see chart).

Mr. Macri's popularity is moving in the opposite direction. An opinion poll last week suggested he would lose Fernández's October elections despite accusations of corruption against her. To overcome her, Macri chose to imitate her, demanding that the stores refrain from raising "indispensable prices" for six months. In a meeting with supermarket bosses, he insisted he would gain from 52% to 48% – that kind of margin that makes retailers nervous.

"Such price agreements will never solve the real problem: never, never," said Miguel Acevedo, president of the country's largest employers' association. In Buenos Aires, freezing and other controls affect only about 3% of the consumption basket, according to JPMorgan Chase, a bank. Many of these prices surged in the few days following the announcement and the imposition of the freeze. And if products are removed from the tablets, they do not fall back into inflation.

But controls can still have an indirect impact, through psychology and politics. Argentina's macroeconomic policies are now compatible with lower inflation: the budget deficit is narrowing, interest rates are painfully high, and IMF strengthened the foreign exchange reserves of the central bank. But inflation has its own dynamic: it is high because it was high and should remain so. The hope is that freezing some very prominent prices could help lower those expectations, at least until the election. While Ms. Fernández's controls have tried, unsuccessfully, to suppress the inflationary effects of loose policies, Macri is trying to reinforce the disinflationary effect of restrictive policies.

This inflationary psychology also depends on the exchange rate, which the Argentineans observe with a fierce fascination. Under the agreement of the country with the IMFthe central bank can intervene to defend the peso if it weakens beyond a "no-intervention zone". This has evolved slowly over time, to allow the peso to deteriorate gradually, thus maintaining competitive exports despite rising peso prices. But for the rest of the year, the central bank will strive to curb the weakening of the currency beyond 51.5 pesos to the dollar, whatever the damage caused to exports.

If the peso holds, inflation should start to fall. And if that happens, Mr. Macri could still be re-elected. According to pollster Eduardo D'Alessio, 71 percent of voters approve the anti-inflation package, which also provides credit for the poor and the elderly, as well as the cancellation of expected increases in electricity and transport prices. But if Mr. Macri's chances of election seem too bleak, the Argentineans could resume their escape in dollars, weaken the peso, aggravate inflation and thus guarantee its defeat. In this way, Argentina could succumb to a self-fulfilling fear of Ms. Fernández. In politics as well as in economics, expectations can precipitate the dangers they foresee.

[ad_2]

Source link