[ad_1]

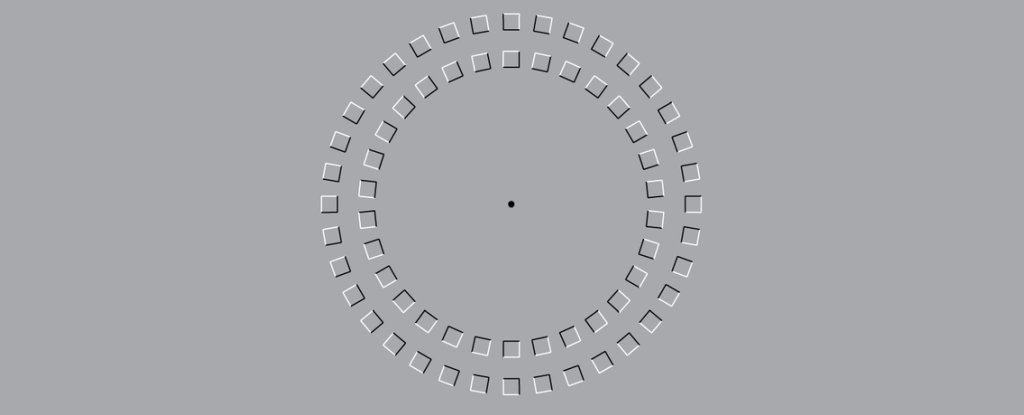

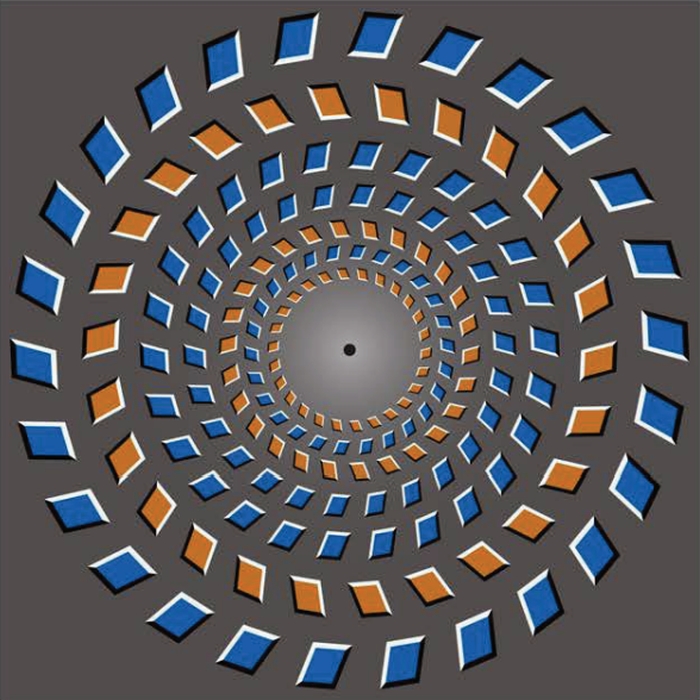

The illusion of Pinna-Brelstaff is extremely amusing: concentric rings of shapes, with reverse shading. When you move your head closer to illusion, the rings appear to rotate, zoom, and contract (continue, we'll wait while you try this with the photo above).

We know that the shading effect helps our brain to perceive movement, even if there is none at all. after all, it is well established that our eyes are lying liars. But now, a team of scientists has been scanning the human brain and the monkey brain as part of two separate studies to try to understand what is really happening when you stare at these dark circles.

"The neural basis of the transformation of objective reality into illusory perceptions of rotation, expansion and contraction remains unknown," the researchers wrote in their article.

"The study of the inadequacy between perception and reality helps us better understand the constructive nature of the visual brain."

Last year, researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to study the brains of 42 humans observing the illusion under different conditions . However, fMRI is limited – it can not reveal the underlying neural mechanisms.

Researchers have therefore turned to male rhesus macaques (Macaca Mulata), by inserting electrodes into their brain to analyze the activity in more detail.

First, they had to determine if the macaques could even perceive the illusions. Nine human volunteers and two macaques studied the illusion (with the stabilized head) of recording rapid eye movements – called saccades – in response to the perception of movement.

The figure of Pinna-Brelstaff used in the experiment. (Luo et al., Journal of Neuroscience, 2019)

The figure of Pinna-Brelstaff used in the experiment. (Luo et al., Journal of Neuroscience, 2019)

Humans have quantified the effect of the illusion – for example, whether the rotation was clockwise or anti-clockwise, and whether it was expanding or contracting when the illusion was getting closer or better. was getting closer.

Both monkeys and humans have had similar responses to the saccade, which means that it is very likely that the monkeys actually perceived the illusion in the same way as humans.

The recording of brain activity was the next part. After recovering from surgery to implant the electrodes, the illusion and animations were shown to the monkeys. They were not told which one was which; they were only trained to indicate the direction of rotation and to determine whether the figure was expanding or contracting.

The team found that illusions activate the same part of the brain as the real movement, indicating that the brain processes illusory and real movements with the same neurons.

But there was a difference: the neurons took about 15 milliseconds longer to process an illusory movement than a real movement.

The causes of this delay are not exactly clear, but researchers believe that the brain could use the extra time needed to record the difference between an illusory movement and a real movement.

In other words, it might sound like movement, but the deep recesses of your brain might know something is fishy and take a split second to think about it. We will however need a little more work to confirm it.

We know that humans and monkeys seem to perceive Pinna-Brelstaff's illusion in the same way; that the same region of the brain treats both real and illusory movements; and that monkeys have an offset of 15 milliseconds when processing illusions.

It goes without saying that the human brain does the same, but more research is needed to confirm it. and also to understand what this farfetched shift is.

"The question remains," the researchers wrote, "whether these upper cerebral areas of the dorsal visual flow of primates distinguish between real and illusory movements during active perception."

The research of the team was published in the Journal of Neuroscience.

[ad_2]

Source link