[ad_1]

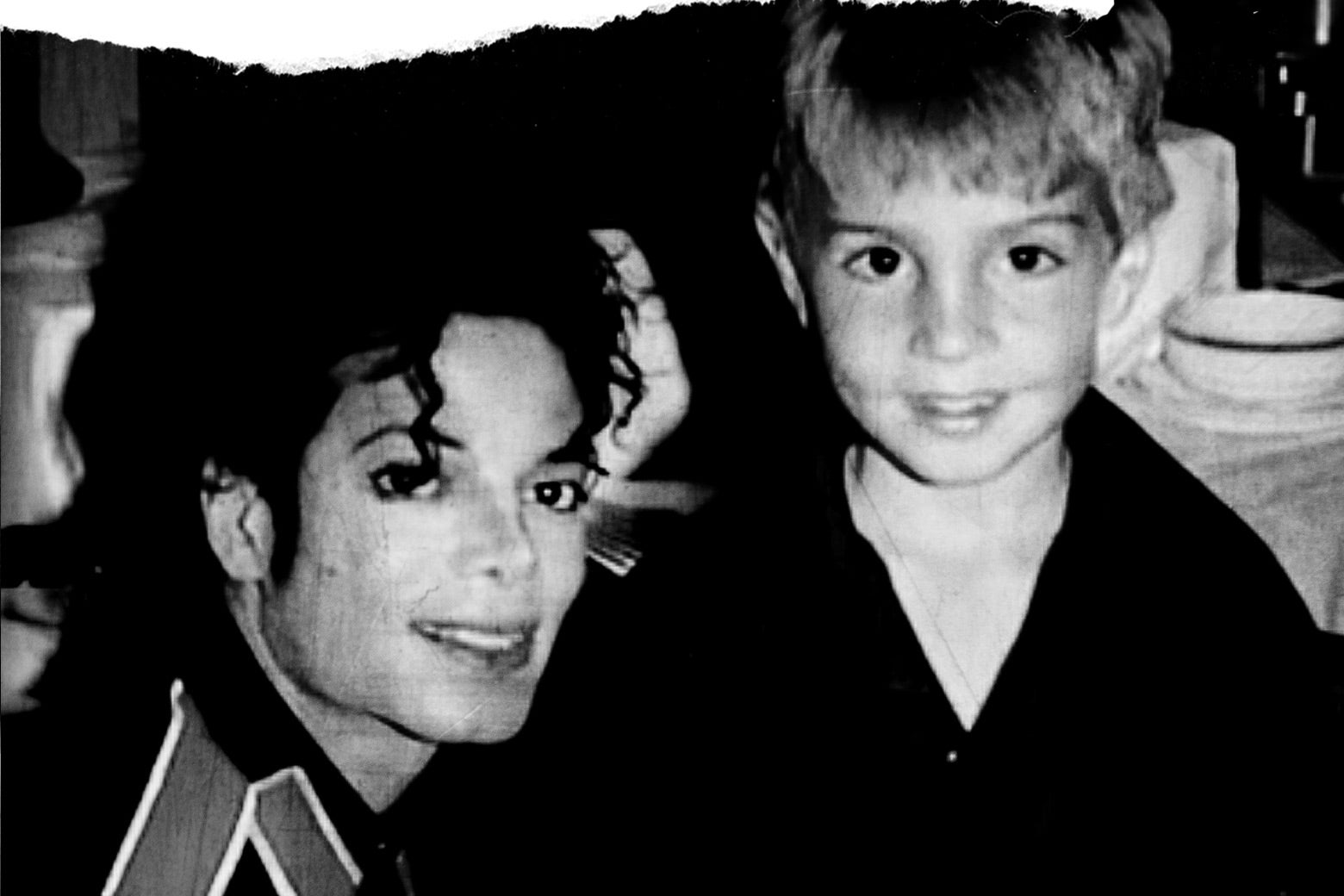

Michael Jackson and Wade Robson.

Photo illustration by Derreck Johnson. Photo by HBO.

The Michael Jackson estate wants to keep Leaving Neverland off the air. The estate alleges that the two-part, four-hour documentary, which premiered at Sundance and will be air on HBO, breaches a non-disappearance clause in the network's "longstanding contractual relationship" with Jackson. It also claims the film violates the ethics guidelines of the U.K.'s Channel 4, HBO's co-producer, which states that any "significant allegations" made in a program should give the subject "an appropriate and timely opportunity to respond."

Neither of these succeeded in delaying the HBO or Channel 4 broadcasts. It is worth noting, though, that Leaving Neverland Director Dan Reed Never Revisited from Wake Robson and James Safechuck, who is both sexually abused as children. Reed says the film's narrow scope-a tightly framed look at the lives of two boys and their families as they are seduced into Jackson's bizarre, rarefied, possibly predatory orbit-was a creative decision. "I did not characterize Jackson at all in the movie," Reed told the Hollywood Reporter. "It's not a movie about Michael. … The movie itself is an account of sexual abuse

The fact that Leaving Neverland It's impossible to defame a dead person. And the focus on Robson and Safechuck's experiences of a gossipfest, a vibe many media outlets conveyed in their rubbernecking coverage of Jackson's 2005 sexual abuse trial. But several critics have already noted the gaps in Leaving Neverland, with Entertainment Weekly calling it "Woefully one-sided."

That one-sidedness has less to do with the absence of Jackson's family than with the movie's lack of candor regarding complicating information about Robson, Safechuck, and two of Jackson's previous accusers. Viewers inclined to look at the allegations against Jackson with skepticism and misgivings to grow. In glossing over, and sometimes entirely excluding, elements of the factual record, the documentary hobbles its chances to convince skeptics that these men are telling the truth. This misstep-one that presumably stems from a desire to protect Robson and Safechuck-actually does a serious disservice to both men, whose stories I believe.

As is, the film provides a bracing account of the alleged victims of sexual abuse. It can not be more perfect than a survivor's relationship. One of the best segments in Leaving Neverland When Robson explains his decision, at 22, to testify on Jackson's behalf at the 2005 trial, where he repeatedly denied that Jackson had ever abused him. Robson genuinely loved Jackson, his childhood hero and frequent babysitter. At the age of 7, when thinking about self-esteem, love, and parenting, his mother encouraged him to think of Jackson as a member of their family-and Jackson's allegedly indoctrinated him with the fear of what horrors might befall both of them if their sexual relationship was ever discovered. These deep-seated attachments and fears do not dissipate on their own when one reaches the age of consent. It's this straightforward recognition of the psychological messiness of abuse that makes the film such a powerful, nuanced portrait of victimhood.

Goal Leaving Neverland denies Robson and Safechuck the opportunity to address other parts of their stories. A Forbes piece published last month by Jackson biographer Joe Vogel notes that Robson once tried and failed to get to Jackson. that Robson shopped around a book proposal about his abuse allegations in 2012; that Robson and his family attended a Jackson memorial show after the singer's death; and that both Robson and Safechuck tried to sue the Jackson estate for assuring the abuse they allegedly suffered. Vogel implies that Robson loved Jackson until he was snubbed by the singer's estate, that he saw a lucrative opening in his role as one of the world's most famous stars, and is now using Leaving Neverland to gin up public support for a lawsuit that a judge dismissed but is now under appeal.

There are more reasons to say that they are more likely than others to suffer from allegations of abuse. Leaving Neverland could not have been more helpful than robson and safechuck. Instead, we're left with the sense that Jackson's accusers look less trustworthy.

Reed also made to recognize that many of the pop star 's fans look askance to any sexual abuse allegations against the singer because of the media and team. Jackson's defense attorneys used the same arguments Vogel and other Leaving Neverland Jackson Chandler and Gavin Arvizo when they are accused Jackson of sexual abuse. Both boys were ill-served by parents whose exploits encouraged suspicions that scams were afoot. Jordan's father Evan Chandler, who died by suicide in 2009, was a dentist to the stars who, according to Carrie Fisher, was better known for providing painkillers than dental services.

Reason for going to the police when his son said Jackson had abused him, Evan Chandler enlisted his attorney to try to get a multimillion-dollar payout by threatening to ruin Jackson's career with the specter of a formal legal complaint. After a couple of weeks of negotiations with Jackson's team, Chandler feels his way to a psychiatrist, who is obligated to notify law enforcement. Jackson's lawyers then produced a recording in which Chandler said, "If I go through with this, I win big time. There's no way I lose. I will get everything I want, and they will be destroyed forever. "In the end, the Chandlers have ended up getting rid of $ 25 million.

It's likely that Jackson has been tested to help their families gain.

Gavin Arvizo's sexual abuse allegations led to Jackson's 2005 trial, in which the defense made the child's parents. Two years before Gavin puts Jackson as a cancer patient in 2000, Janet and David Arvizo took their kids to a J.C. Penney and allegedly instructed them to walk out of the store with a bunch of clothes. The family was arrested and detained by security guards; afterward, the Arvizos sued J.C. Penney, claiming Janet had been physically assaulted and sexually molested by a guard. They got a $ 152,000 settlement. With Janet on the booth at Jackson 's trial, her attorneys revealed that she had been brought to the forefront by 2001 and 2003 without disclosing the money. It was an unidentified private investigator-possibly hired by Jackson's team-who tipped off welfare authorities about Janet's alleged fraud just a few weeks before the 2005 trial began. (Janet Arvizo pleaded no contest to a single fraud count in 2006 and did not jail time.)

Leaving Neverland does not get into either of these stories. The film mentions the Chandler and Arvizo cases only as they apply to Safechuck and Robson, squandering an opportunity to re-contextualize the old accusations and thus bolster the newer ones. If Safechuck and Robson were teens today, the Jackson estate could make their stories into the same story that was used in an attempt to discredit Chandler and Arvizo. The mothers of Safechuck and Robson, both of whom gave extensive interviews for the film, come across as pushy managers eager to compromise their family relationships and their children's safety for stardom access and a life of luxury. They took their kids out of school for a time to follow Jackson around. Both accepted lavish trips and gifts from Jackson, Safechuck's mother, an entire house. And then ended up transferring parental duties to Jackson for extended periods of time.

How much distance is there between parents who do not know and what do you think? This is one difficult, emotionally muddled issue Leaving Neverland handles with admirable frankness. Reed prods Robson, Safechuck, and their parents to be responsible for their sounds, abuse, abuse, abuse, abuse, abuse, abuse on a family, and a firmer sense that all parties are telling the truth. The film covers this ground, it seems, because the question of parental blame was one that Robson and Safechuck were ready and willing to confront. Leaving Neverland'S limited purview means it only goes where Robson and Safechuck want it to go.

In the segments about Robson and Safechuck's mothers, Leaving Neverland suggests that the parents of the four people who have They are exhibited to manipulate their sounds for profit, making them both exploitative and easy to exploit. The Jackson estate has used this common thread to argue that all the families are lying, that there is a pattern of swindlers trying to extort money. But it is much more likely that those people are willing to use their sounds as conduits for personal gain. In fact, those were probably the only boys to whom they had sustained access: those whose parents took the steps to get their kids in front of Jackson, who accepted his invitations to Neverland, and who went along with his pleading to the boys sleep in his room and be his "traveling companions" on tour. It would be a surprise to have a sexual assumption that the very thing that these boys at risk would also make them and their families seem less credible to a jury and the general public.

Had Leaving Neverland Chandler and Arvizo 's accounts are more likely to be misleading than Jackson' s. In the movie, Robson's sister admits her tears that she once made the same out-of-money arguments against Chandler and Arvizo that make her face up. But without explaining why those arguments took hold, Leaving Neverland falls short of dismantling them.

[ad_2]

Source link