[ad_1]

A 99-year-old woman living in Oregon has lived a long life in one of the rarest and often deadliest states in the world: a body in which most of her major organs were on the wrong side. Even more surprising, the woman remained completely ignorant of her unusual situation. It was only after medical students and their teacher were able to study his body, which she gave to science, that this strange arrangement of organs was discovered.

Cam Walker, professor of anatomy at Oregon Health & Science University, explained in detail the amazing case of women in a presentation given at the annual meeting of the American Association of Anatomists. And although the identity of a person who donated his organs or body is usually kept secret, the family has agreed to reveal his name: Rose Marie Bentley.

"I knew something was wrong, but it took us a while to understand how it was prepared," Walker said in a statement.

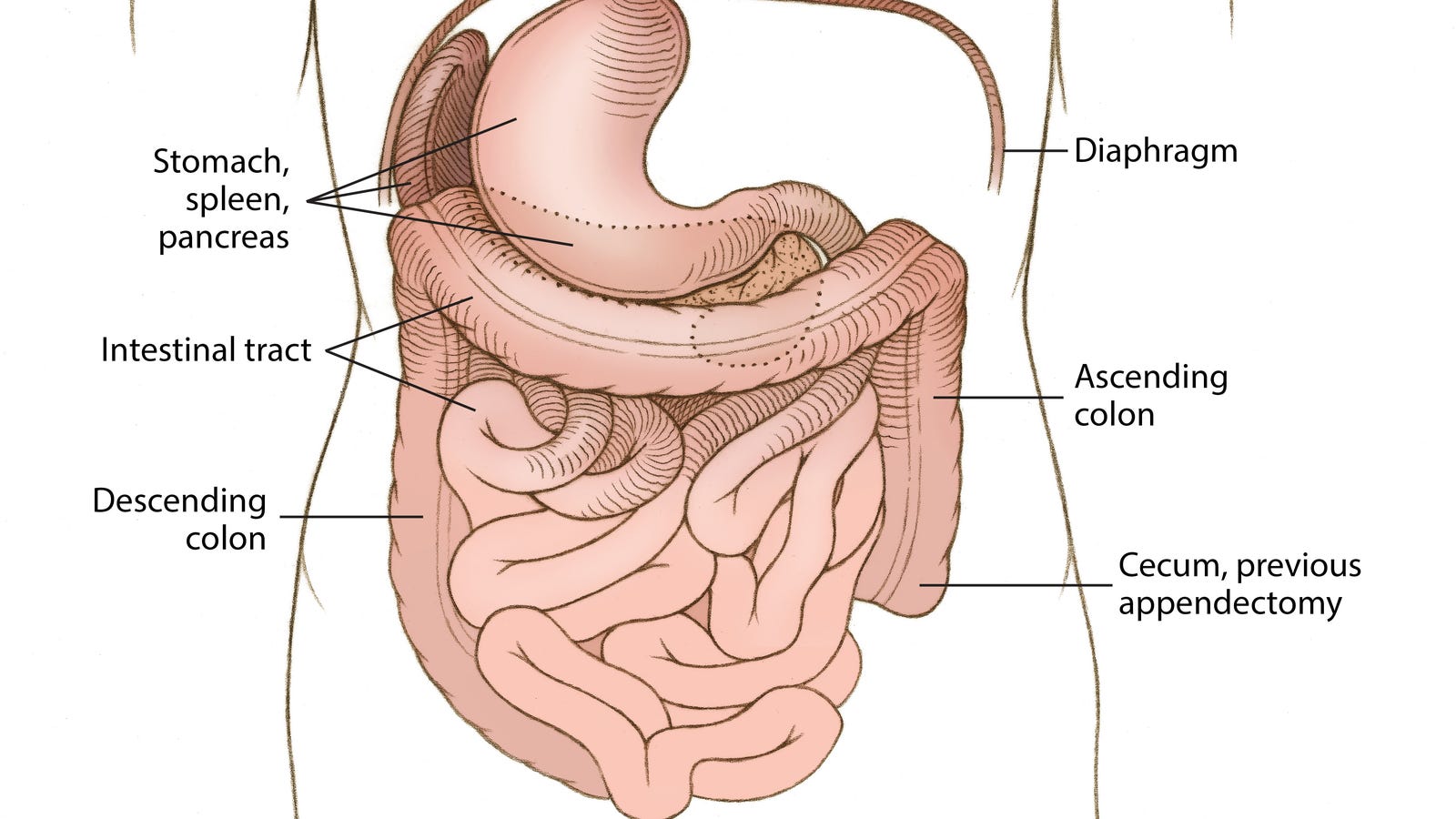

Walker eventually determined that Bentley was suffering from a congenital condition called "situs inversus with levocardia". This meant that Bentley's organs inside the chest or abdomen were identical to those of the average person, with the only exception of his heart remaining to the left. side of his body (levo being Latin for left).

People may have different organ arrangements gone astray, but this particular combination – mirrored organs, but a normally placed heart – is certainly rare, occurring in only one in 22,000 births, according to Walker. And Bentley's long life was particularly unusual.

"Normally, what makes [situs inversus] surviving is that all organs do the same trick. So if the organs of the abdomen are transposed from right to left and the heart follows, it's great, "Walker told Gizmodo. "But when the heart stays pointed to the left, as with this donor, the blood vessels must change orientation, and this change in orientation usually results in serious heart defects."

These defects of the heart (and often also of the spine) are usually fatal and only 5 to 13% of people born with this disease live after the age of five, according to the limited research available. When Walker looked further, he could only find two other cases of similar people living up to the age of 70 in the medical literature. Bentley's survival was therefore extraordinary. He estimated approximately that the probability that someone with his exact medical situation reaches adulthood reaches one in 50 million.

Given Bentley's unique case, Walker received permission from his university's body donation program to contact the family about what he and his students had discovered.

"They were immediately happy to be contacted and allowed us to do a descriptive case study and use some of their information when discussing her case," Walker said.

According to her family, Bentley lived a relatively healthy life until her death in October 2017. She did not suffer from any other known chronic health condition, aside from arthritis. And although three organs were collected over the years, only one doctor noticed that his appendix was not exactly where he was supposed to be. Walker and his team noticed that the upper part of Bentley's stomach had passed the diaphragm, the muscle that separates the chest from our abdomen, a condition called hiatal hernia. But it seems that Bentley herself has never noticed anything wrong with her guts.

According to Louise Allee, one of her children, Bentley would appreciate the extra lesson that she could give to Walker and his students.

"My mom would think it's so cool," Allee said in a statement. "She would be tickled in pink to be able to teach something like that. She would probably have a big smile on her face, knowing that she was different, but succeeded.

Walker says his students were also grateful for the knowledge that Bentley's case had conveyed.

"It allowed them to discover this strange anatomical variation and to show how this donor was such a unique individual. And that should translate into their professional practice, "said Walker. "When they see new patients, it's important that they realize that even though our surface anatomy has great similarities, we are all a little different … every time."

[ad_2]

Source link