[ad_1]

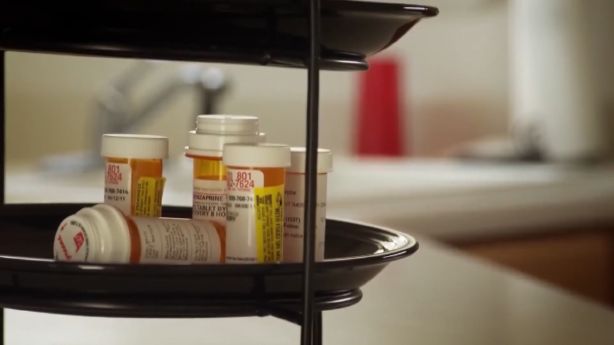

SALT LAKE CITY – While Utah and the country are tackling the epidemic of opioids, many people with chronic pain have suffered when doctors have removed or decreased their medications Monday said a lobbyist to lawmakers.

According to Amy Coombs, Amy Coombs, who has worked with drug addicts and is executive director, some people find it difficult to get their prescriptions from pharmacies and others are "forced" or suddenly made to order. opioids, which can lead to severe opioid withdrawal symptoms. the government relations and prestige consultancy group.

Coombs made a presentation to members of the health reform task force as the group discussed opioids, health care costs and the expansion of Medicaid at a tentative legislative meeting on Tuesday. on Monday.

In April, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that their 2016 guidelines on opiates had been "widely misapplied" to include those who used opioids for palliative care, chronic pain and diseases such as cancer, said Coombs.

According to Coombs, there has been a "broad brushstroke" to reduce or reduce opioids to people, but opioids must be considered person-to-person.

Also in April, the Food and Drug Administration issued a warning and requested labeling changes after receiving "reports of serious damage in patients physically dependent on opioid analgesics." These drugs were suddenly discontinued or their dose decreased rapidly, uncontrolled pain, psychological distress and suicide ".

Coombs said that many patients were receiving opioid treatment. She has heard more and more stories about people in Utah who have committed suicide or have suffered severe setbacks in managing their pain due to too fast changing their prescriptions d & # 39; opioids.

Some have turned to illegal drugs, according to Coombs. "People do not get the care they need."

Those who need opioids are now finding it harder to find access to quality care and providers willing to treat their chronic pain, she said. People who have been taking opioids for years often have to wait for pharmacists to consult their doctor before prescribing prescriptions – and are suffering from withdrawal symptoms in the meantime, she says.

Representative Jim Dunnigan, R-Taylorsville, asked what could cause this delay.

Senate Majority Leader Evan Vickers, R-Cedar City, himself a pharmacist, explained that there is a "mismatch" between the decisions made by health care plans and the pharmaceutical benefit managers who " are not necessarily based on medical criteria "but" often on a financial basis ". "

Health insurance plans consider the fight against the opioid crisis as "a strict and fast rule and do not leave much room for maneuver," Vickers said.

Opioid patients who have been prescribed large amounts of opiates must be reduced gradually to achieve long-term results, according to Vickers. But often, health plans do not allow for a gradual reduction in size.

"And that forces (the patients) to make choices that they probably would not normally do," including finding drug sources on the street, Vickers said.

Senator Allen Christensen, R-North Ogden, noted that the issue of opioids had been "beaten to death". But opioids are "miracle drugs," he said.

"We have to move the pendulum a bit, we have to regulate it, but do not overreact, we are trying to find that healthy medium in the middle," he said.

Coombs said the patients had also suffered, with doctors being encouraged to reduce opioid patients and less motivated to treat opioid pain patients.

She urged the task force to work toward creating a definition of palliative care or an exemption to help those who need long-term opioids to receive them. She also encouraged patients to create "bridges" to receive supplies of two to four days so that they do not suffer withdrawals while doctors and pharmacists solve problems such as authorization.

Several lawmakers agreed that Coombs posed a real problem, but no potential action plan was discussed at the meeting.

"I think it's a problem, you have to find someone who thinks it's enough of a problem to try to do something about it," said Christensen. pointing out that a legislator "pharmacist" would be a good candidate to solve it.

Suzanne Harrison, D-Draper, said, "I think this raises the question: we need to make sure that we provide evidence-based care and adequate access to those providers who have the qualifications."

Related stories

[ad_2]

Source link