[ad_1]

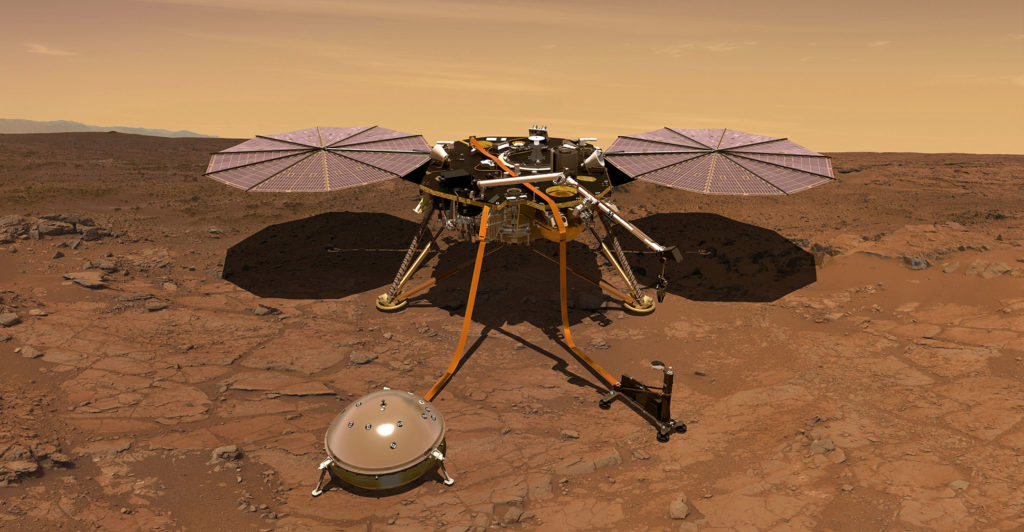

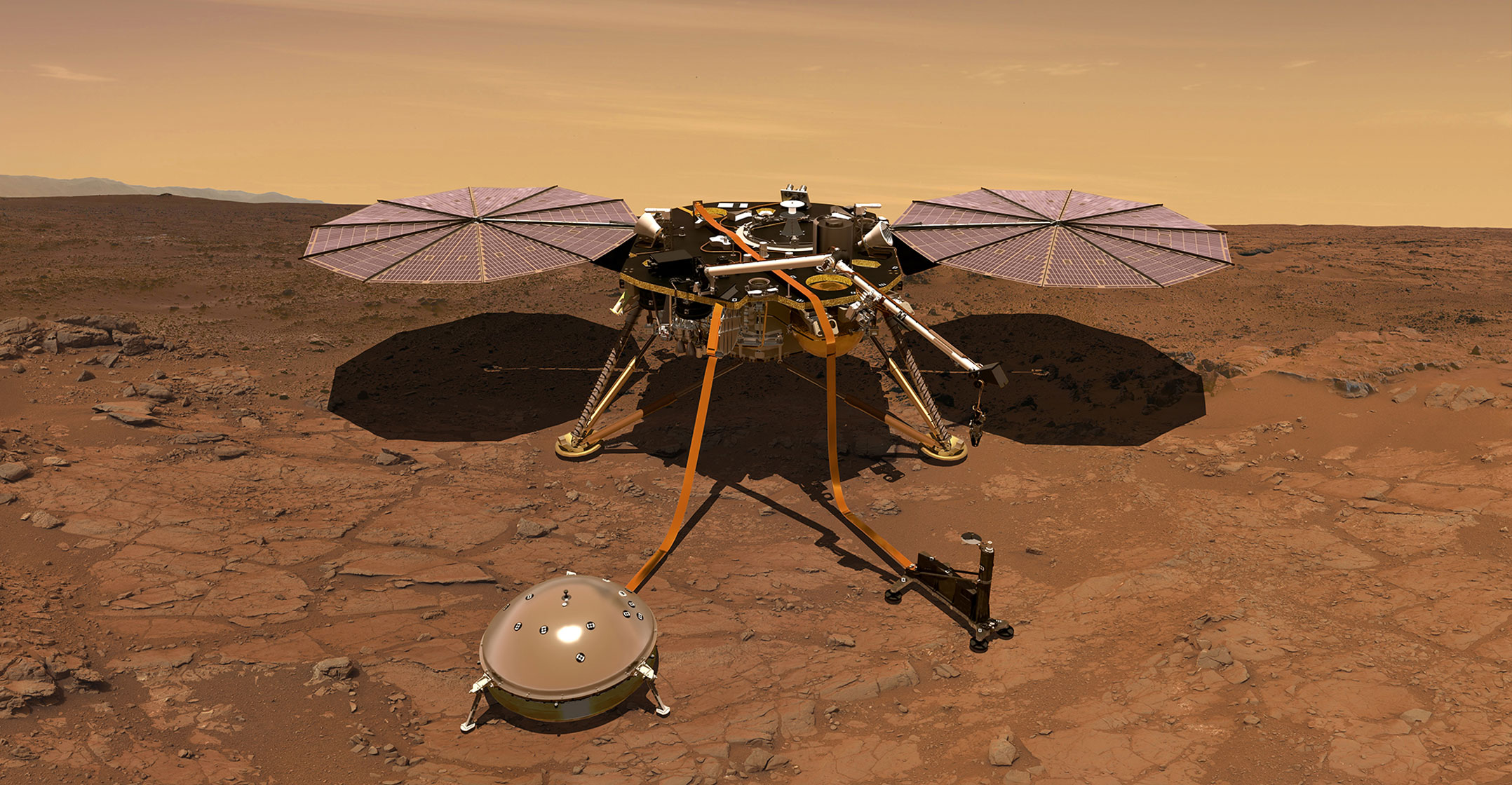

Artist's impression of the Mars undercarriage. Image: Nasa

It's notoriously Hard to land on Mars, and yet NASA did exactly that with its recent InSight lander. Since my childhood, I love watching landings and other maneuvers from spaceships on TV – I always feel a bit of that excitement at the edge of the seat. But that did not prepare me for the feeling of looking at a mission I worked on. Each period of silence that followed the seven-minute descent of InSight was perceived as an eternity, the time being spent only when calls Christine Szalai, computer systems engineer. I will never forget the joy of the moment she finally announced "touch confirmed".

The InSight mission has been planned for more than 10 years. Among the planetary missions, it's a bit strange. While most missions are designed to examine the surface or atmosphere of planetary bodies, InSight's goal is to look deep beneath the surface, allowing us to unravel the mystery of its formation and that of other planets. rocky.

The LG carries a number of instruments, including seismometers, a heat flow sensor, a magnetometer and a radio transmitter. The heat flux and physical properties (HP3) probe will hammer to a depth of five meters below the surface of Mars, almost twice as far as lunar missions hand exercises. His measurements will tell us how quickly heat is lost from the inside of the planet, allowing us to understand how Mars is cooling over time.

The Rotation and Interior Structure Experiment (RISE) will basically return a radio signal sent from the Earth upon our return. The difference in frequency between the original signal and the returned signal can then be used to calculate the speed of the InSight lander compared to the Earth, much like the sound of a siren tells us if it gets closer or farther away from us. We are particularly interested in the use of speed to tell us how the axis of rotation of Mars wobbles in time. The size of these oscillations depends on the structure of the interior, including its dense metal core. Just as a raw egg wobbles more than a hard egg when it rotates on a flat surface, Mars will stagger more if its core is liquid.

seismometers

I am working on the Seismic Experience for Interior Structure (SEIS), which consists of two seismometers mounted on a leveling system that will be about 15 cm above the surface of Mars. This experiment is designed to tell us the amount of seismic activity on Mars. We will also use the time required for seismic waves to reach the seismometers and provide information on the temperature and composition of the interior, much like a doctor uses a scanner.

We now have about three months during which the instruments will be deployed and activated. Over the next few days, the health of the systems will be verified and the LG and surrounding areas will be thoroughly imaged so that the operations team can decide where to place the heat flow sensor and the InSight seismometers. The first image taken from the surface suggests that we landed on a shallow crater filled with sand, almost devoid of rocks. It seems so that there will be many options.

Around mid-December, a robotic arm will lift the seismometers mounted on a tripod from the LG deck and lower them to the surface. After detailed checks, the leveling system will be used to ensure that the seismometers are perfectly horizontal. By mid-January, a shield should be placed over the seismometers to protect them from the elements. Then they can be turned on and the heat flow sensor will be deployed.

Around mid-December, a robotic arm will lift the seismometers mounted on a tripod from the LG deck and lower them to the surface. After detailed checks, the leveling system will be used to ensure that the seismometers are perfectly horizontal. By mid-January, a shield should be placed over the seismometers to protect them from the elements. Then they can be turned on and the heat flow sensor will be deployed.

The heat flow sensor will begin to return the data as soon as it starts to sneak under the surface. So we hope to get results in the first half of 2019. The radio experience will take a little longer. It turns out that over the next year we will not be in the best position to see the flickering pole of Mars. This changes in mid-2020, when we should be ideally located to discover the secrets of its core.

With regard to the SEIS experiment, the excitation depends on the frequency with which the seismic energy is generated. We do not know it right now. What we do know is that there are two potential sources of seismic activity: meteorite impacts and "earthquakes" created by movement along faults close to the surface.

Although we know that meteorites frequently hit Mars, the rate of displacement of the fault remains a mystery. Unlike Earth, Mars does not have tectonic plates in motion. It is therefore believed that the movement of faults occurs when the interior of the planet cools. However, some of the youngest faults on Mars seem to have been formed not by cooling but by the movement of molten rock beneath the surface. Discovering the frequency and nature of marsquakes will help us determine the exact causes.

Through its three main experiences, InSight will provide a "snapshot" of the current state and composition of Mars. But this is not where the scientific discoveries will end. Eventually, the mission will help us understand the processes that took place more than 4.5 billion years ago, when the solar system was very young.

Basic key

Here's why. The composition of a planet is defined during its formation, which in the case of Mars only occurred a few million years after the sun ignited. We think that because of its greater distance to the sun, Mars is formed from a different material, richer in volatiles than the Earth. However, until the composition of Mars is known, this idea is very difficult to test and develop. The data returned by InSight will provide a fundamental key to understanding how the rocky planets of our solar system were formed – and perhaps even those surrounding other stars.

The composition, temperature and magnetic field of our planet are also essential to maintaining life on our planet. Thus, even if InSight does not seek life, it will give us new clues as to how the Earth was prepared for life more than four billion years ago.

InSight is already experiencing tremendous engineering success and the scientific team now has the incredible opportunity to use it to reveal the secrets of Mars. We hope you are as excited as we are.![]()

- Written by Bob Myhill, Postdoctoral Fellow, British Space Agency, University of Bristol

- This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license

Source link