[ad_1]

Photographer: Edwin Remsberg / VW Pics / Universal Images / Getty Images

Photographer: Edwin Remsberg / VW Pics / Universal Images / Getty Images

Americans have become, by certain measures, richer than ever during the pandemic.

It is a difficult thing to understand, with the economic collapse and the skyrocketing of the unemployed, the homeless and the hungry. But there is a whole class of people – at least the richest 20% of earners – who have not had to worry about these issues.

For them, not only was it relatively easy to do their white collar work from home. But the The Federal Reserve’s unprecedented emergency measures – including cutting benchmark rates to zero – have also padded their portfolios. They refinanced their mortgages at historically low rates, bought second homes to get away from cities, and saw the value of stocks and bonds in their investment accounts rise.

Their massive accumulation of wealth is, in large part, obscuring the toll felt by all those who do not have the same easy access to credit or to financial markets. As household net worth hits a new record, hundreds of thousands of businesses would have closed permanently, more than 10 million Americans would be unemployed and nearly three times more hungry at night.

Even though a new Democratic administration plans to seek Billion in additional spending to complement last month’s Covid-19 relief program, economists warn of dire social and political consequences of America’s dramatic widening gap between haves and have-nots . With income inequality already nearing its highest for at least half a century, the country’s response to the financial devastation wrought by the coronavirus raises questions about who the emergency measures were designed to help and who has been left behind, they say.

“There probably hasn’t been a better time to be rich in America than today,” said Peter Atwater, assistant professor at William & Mary, who popularized the notion of K-Shaped recovery to describe the deep division of economic fortunes. “Much of what policymakers did was allow the wealthiest to bounce back sooner from the pandemic.”

Over the past 10 months, high income earners have, relatively speaking, been in a very good position.

Employment for According to data from Opportunity Insights, a non-partisan research institute based at Harvard University, the top quartile of workers – those who earn more than $ 60,000 a year – have already recovered above the levels of it. a year ago.

And as the lockdowns took hold of the nation, millions of people, especially those at the higher end of the American socio-economic ladder, were able to redirect the money they would otherwise have spent on things like entertainment, meals, and travel to savings or better yet, investments. .

For many, it has paid off. Thanks to the Fed’s efforts to support the economy, US stocks hit record highs in the aftermath of the outbreak, while bonds rose the most last year in more than a decade.

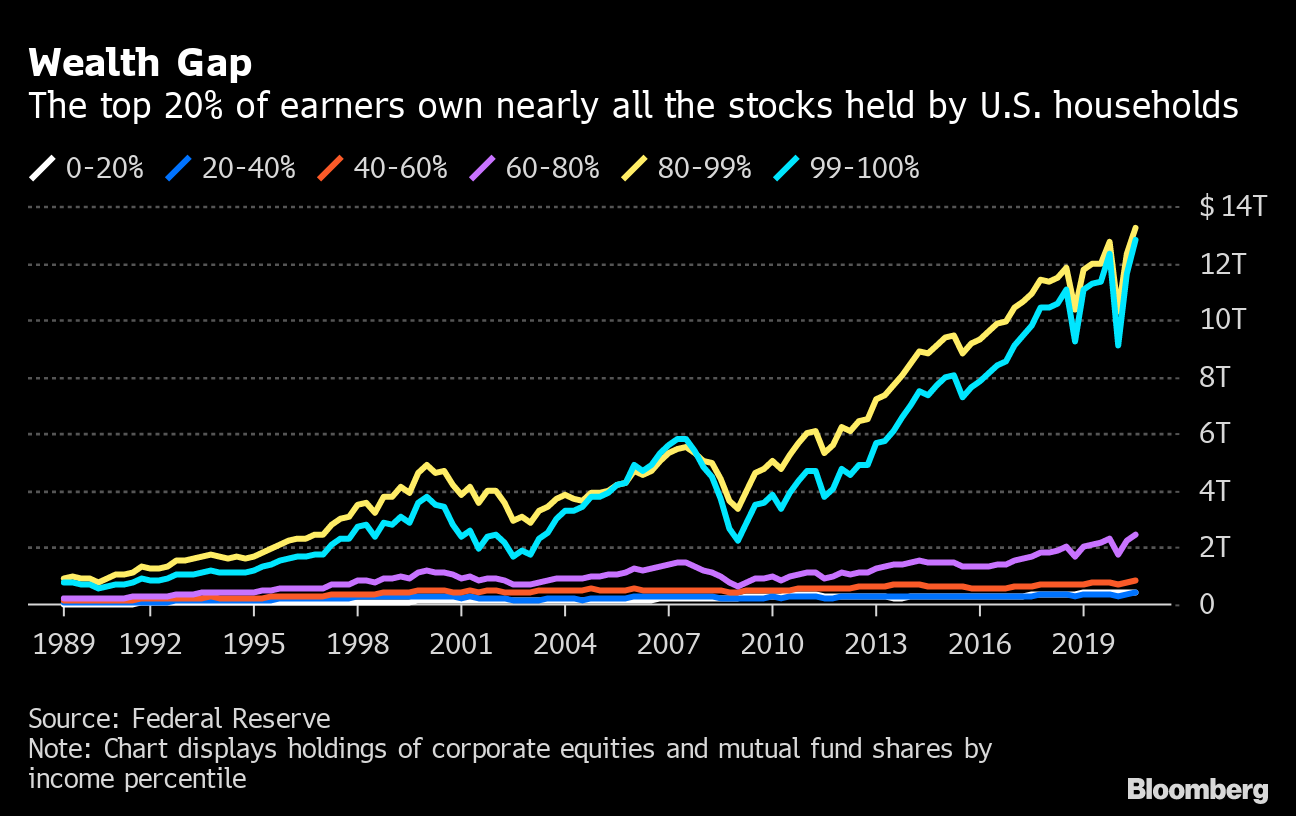

Wealth gap

The richest 20% own almost all the stocks held by American households

Source: Federal Reserve

“If your wealth is captured by financial assets, you are back up and running in no time,” said Amanda Fischer, director of policy at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. “It’s the people with the lowest incomes who don’t even have to file their taxes who have the biggest hurdle.”

As their investment accounts skyrocketed, affluent Americans received another giveaway.

Mortgage rates, driven in large part by the same forces that pushed stocks to sky-high, have plunged to lows checked in.

Homeowners, especially those with impeccable credit scores, have benefited. Refinancing accelerated in faster for nearly two decades, according to data from Fannie Mae, helping millions of borrowers lower their monthly payments.

Fall behind

For those on the other end of the spectrum, things are very different.

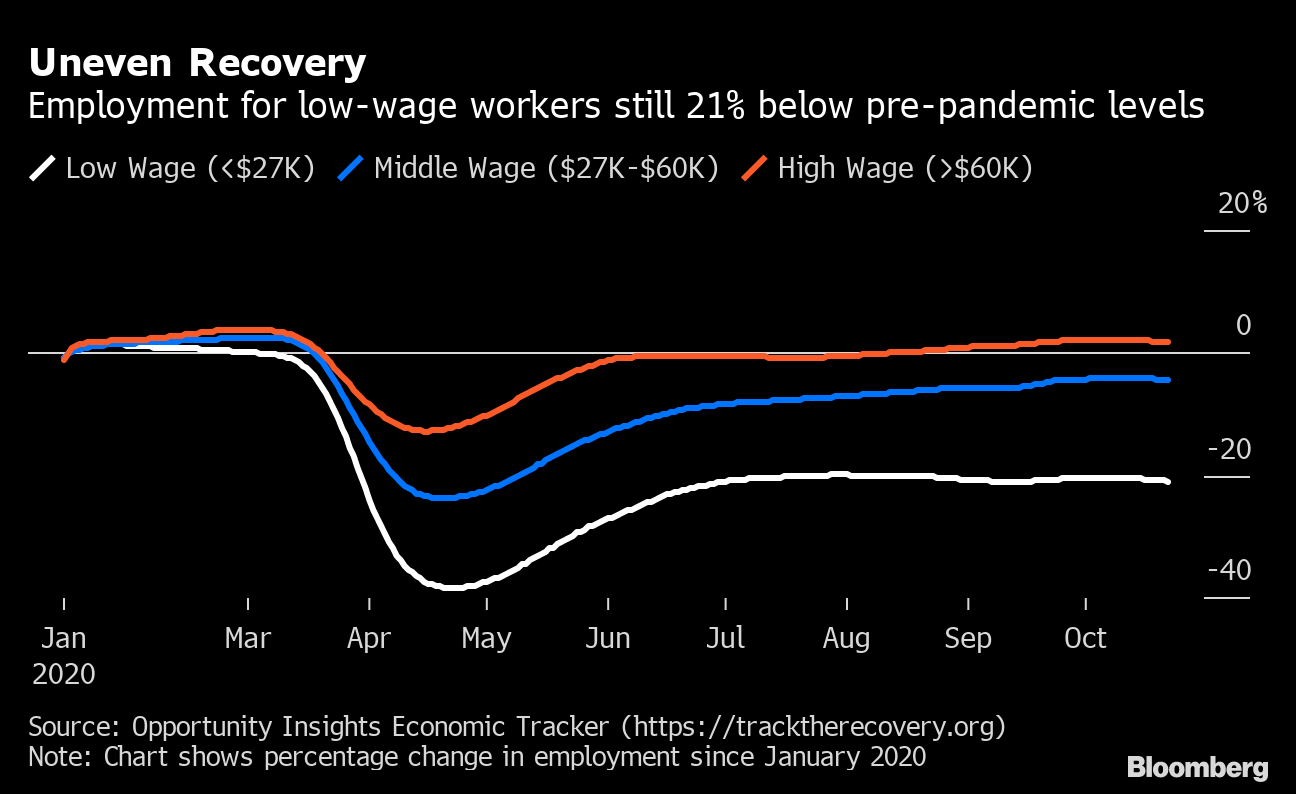

Employment for The bottom quartile of American wage earners – those earning less than $ 27,000 a year – remains more than 20% below January 2020 levels. As of last month, nearly 30 million adults lived in households where they don’t. there was not enough to eat, according to the US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, up 28% since before the pandemic. In Louisiana, the worst-affected state, one in five people now face a food shortage, according to the survey, with the numbers even more dire among black Americans.

Uneven recovery

Employment of low-wage workers still 21% below pre-pandemic levels

Source: Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker (https://tracktherecovery.org)

Millions of people are busy figuring out how to keep their homes rather than borrowing against them. According to the Census Bureau’s December survey, more than a third of American adults who live in households that have fallen behind on rent or mortgage payments are at risk of eviction or foreclosure within the next two month.

As the rollout of the first Covid-19 vaccines instills more optimism in financial markets, many debt-stricken borrowers find it harder than ever to see a path to recovery, even after the additional relief measures approved by Congress in December.

“People simply feel whether they are near or at the bottom of the stone “, declared Bradford Botes, principal of the Bond & Botes bankruptcy law firm in Birmingham, Alabama. “We hear a lot more desperation.”

Botes said that for many of the people his company has advised in Alabama, Tennessee and Mississippi, government unemployment benefits and stimulus checks just haven’t reduced it.

“This money was used by people just to get by,” he said. “The extra stimulus was not enough to make any difference for average Americans.”

‘Rusty plumbing’

To be clear, the tax packages adopted by Washington were among the largest the country has ever seen and have largely targeted the most needy in the country. In coordination with monetary stimulants, they have no doubt helped many Americans keep their jobs and put food on the table.

Yet the growing economic inequality that has accompanied these efforts illustrates the limits of the response, critics say.

By easing credit terms through the Fed, lawmakers were able to quickly support large corporations and richer individuals. But delivering aid to small businesses and working poor has proven to be much more difficult.

Delays in delivering aid, as well as confusion over rules and eligibility criteria, have hampered many of these programs.

Read more: The Fed wakes up Until race – in the new fight for equality

Of course, it is no coincidence that the cogs of monetary policy worked smoothly while the tax equivalent stuttered. It is seen more regular use.

For about four decades, U.S. governments largely delegated business cycle management to an independent Fed – in keeping with the economic orthodoxies of the day, but falling thorough review. Fiscal policy, better suited to regulating the sharing of the cake, has fallen out of fashion except as a tool of crisis. And during this same period, inequalities continue to widen.

According to Fischer, the pandemic has shown how the infrastructure the U.S. government could use to reach everyday Americans is shattered and in urgent need of reform.

“Congress has done a really good job of getting money to people, but we have failed to fix decades of rusty plumbing,” she said. “The fact that the Fed has the infrastructure to do a bond buying program but do nothing else is a choice, not a fate.”

More help

For their part, Fed officials have consistently acknowledged that monetary stimulus is far from a panacea and that the central bank has only limited tools to target specific economic outcomes.

“The Fed cannot give money to specific recipients,” Fed Chairman Jerome Powell told reporters at a December 16 press conference. “Elected officials have the power to tax and spend and to make decisions about the areas in which we, as a society, must direct our collective resources.”

A central bank spokesperson declined to provide further comment.

On fiscal policy, many economists argue that failure to act on another round of stimulus could delay economic recovery just as vaccines are rolled out to the general public.

Millions of people will see their unemployment benefits expire in mid-March if measures approved by Congress in December are not extended. States and local authorities, for their part, may be forced to further reduce their already stretched budgets to compensate for lost tax revenues.

“Without more help, they will have to make more cuts and cut services, which will disproportionately affect low-income families and communities,” said Heidi Shierholz, who was chief economist for the Department of Labor. under the Obama administration and is now in Economics. Institute of Policy. She said comprehensive aid to state and local governments and additional benefits for the unemployed should be the priority of the next round of measures.

Economists like Atwater are also sounding the alarm on the long-term consequences of widening income inequality, which has been associated with a economic growth, higher crime rate and increase social unrest.

“You cannot have a sustainable economy and political system where you have a small population that believes itself to be invincible and a growing population that feel defeated, ”he said. “It is in the best interest of capitalism to close this gap.”

– With the help of Ben Holland

[ad_2]

Source link