:quality(85)//cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/OPCLJXHPHBCMNCN5GO2KAGLPA4.png)

[ad_1]

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/SJGGYM55L5HUBJK7T44ZD5UJYA.jpg 420w)

In 1963 Paulo freire he didn’t have a beard. He was married, had children, 42 years old. He had studied the philosophy of language, had taught in high school, had held important positions as an education official. At that time, he was already applying something similar to liberation theology in his classes: in Brazil at that time, reading and writing were requirements for voting. In 1963, he felt that it was time to take the plunge: he already had the tools to generate something in education that was not simply to reproduce the material conditions of existence, so he and a small group of The teachers left for Angicos, in the center of the state of Rio Grande do Norte, 170 kilometers from the populous Natal. The objective was to educate 300 adult peasants in 40 hours of evening classes.

The method was to contextualize and personalize the teaching, not working with textbooks and brochures where they had to learn how to spell “the beef slime” and “the grandmother saw the grape”, but rather use the world. surrounding the students. to reveal vocabulary and construct meaning: “brick”, “cement”, “cane”, “earth”, “harvest”. It was also not about the educator passing on knowledge, from top to bottom, to passive subjects who do not question what they see, but rather about socializing this knowledge to transform it during the process. learning. It was not about memorizing and repeating, as was the custom at the time, but about thinking, criticizing and creating. The experiment worked. The initiative became known as “40 Hours of Angicos” and began to be incorporated as an educational program.

The peasants attended the lessons with their children. “The words were projected on the wall through slides. For example: brick. The teachers explained how it was made, where it was used, how much it cost, and with that the letters and syllables were worked on, ”he says. Maria Eneida Araújo in an interview with Leaf of St. Paul. She was six at the time and she was one of the many angelic girls who learned to read and write alongside her parents. There were more words: the vote was one. At the end of the day Freire formed critical citizens who were to exercise democracy. But that did not last long: the following year, in 1964, a coup d’etat overthrew the president. João Goulart the establishment of a dictatorship. The soldiers arrive in Angicas and set fire to the peasants’ notebooks.

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/PNZWI4IXARDTVCM3ZPS7QCCYNA.png 420w)

In the city of Recife, capital of the state of Pernambuco, on September 19, 1921, he was born Paulo freire. Son of a military father and a housewife mother. Thanks to them and to his three brothers – a schoolteacher, a commercial employee and a soldier – who began to work very young, he was able to devote himself to his studies. The Marxist conception of the world arrived in this way, read, think, study. The soldiers of the coup d’etat of 64 considered him a communist. They went to get him and put him in jail for 70 days. When he left, he went into exile, first in Bolivia, then moved to Chile. When he arrived in the south of the country, an agrarian reform was under discussion. The aim was to overcome the agricultural crisis and to redistribute land in an equitable manner. The process was interrupted in 1973, with another blow, that of Auguste Pinochet. Until then, more than 6 million hectares had been expropriated.

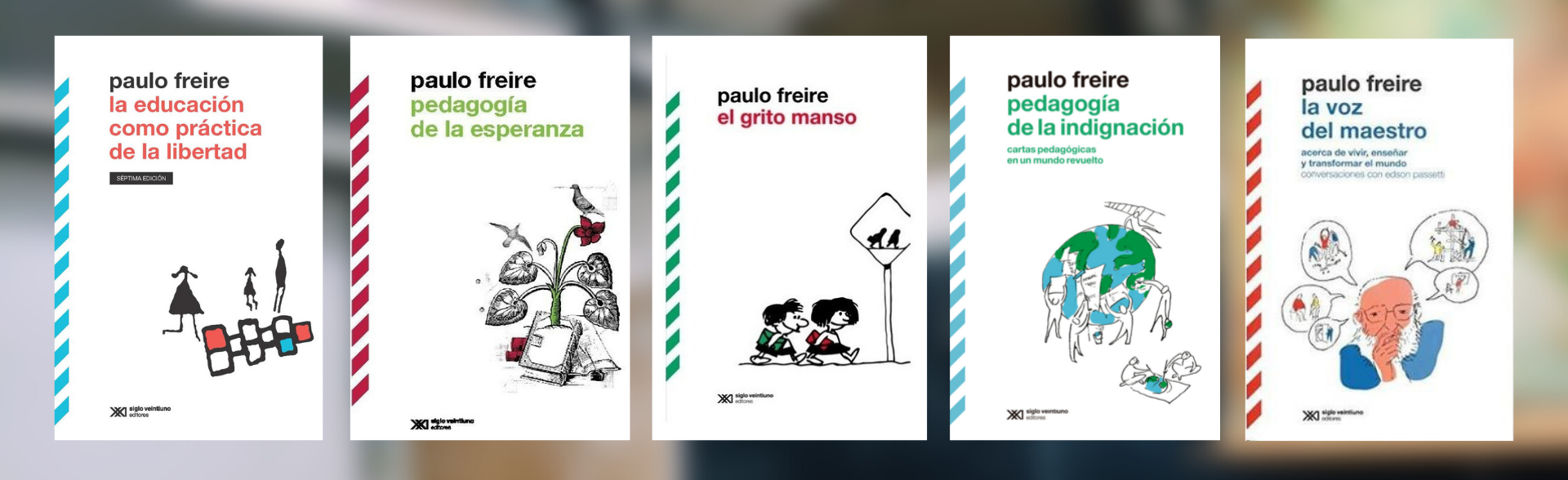

In Chile, Freire worked for five years for the Christian Democracy Agrarian Reform Movement and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. He published his first book there, Education as a practice of freedom, from 1967, where he posed the dichotomy between “education in alienated domestication and education in freedom”, that is to say “the education of the man-object or the education of the ‘man-subject’. Between this year and the next he wrote his great work, Pedagogy of the oppressed, in the spring of 1968 while living in Santiago de Chile. The opening sentence, the dedication that has become iconic, says: “To the ragged peoples of the world and to those who, discovering themselves in them, suffer with them and fight with them.”

Chilean agrarian reform, exiles, emerging dictatorships, armed organizations and the cold war were elements that influenced his writing. “I lived the intensity of the experience of Chilean society, of my experience in this experience, which made me rethink the Brazilian experience, of which I had taken the living memory with me in exile”, says he in Pedagogy of hope: reunion with the Pedagogy of the oppressed (1992); He spoke “with friends who have visited me, I have discussed it in seminars, in classes”, and one of them “suggested more moderation on my part to try to talk about the Pedagogy of the oppressed not yet written. I didn’t have the strength to live the suggestion. I continued to talk passionately about the book as if it were, and was actually learning to write it. “

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/CDEO67S5RZCGJLNAF7UBCONXS4.jpg 420w)

According to the researchers José Eustáquio Romão and Nattacha Priscilla Romao, the first edition was twofold: in English by the American label Herder & Herder, and in Spanish by the Uruguayan publishing house Tierra Nueva, both published from 1970. Translations into Italian and German followed in 1971, in Portuguese in 1972 and in French in 1974. That year, 1974, it was the first time that his book landed in Brazil. The Paz e Terra seal published, according to the researchers, a “mutilated work” which “had the knowledge and consent of the author” in order to circumvent military censorship, a text which “continued to be published in the same way afterwards. the democratization of Brazil, from 1985, maintaining the mutilations in more than 60 editions ”.

The basis of the book is critical pedagogy. Freire takes postulates from Hegelian dialectics, Marxist materialism, and critical theory from the Frankfurt School to analyze the “colonized subject” in the Latin American context. “Homes and schools, elementary, intermediate and university, which do not exist in air, but in time and space, cannot escape the influences of objective structural conditions,” he writes. In this sense, he highlights the classism of capitalism and illuminates the class struggle as an issue, strongly criticizes what he calls “banking education” – the top-down relationship between an “absolute sage” who deposits data in the head of an “absolute ignorant” – and proposes to give voice to the oppressed so that they “historicize” and thus rewrite the world.

He died in 1997, at the age of 75, and yet his ideas have not died out. In his country, he was Secretary of Education in Sao Paulo between 1989 and 1992, he designed major educational policies and influenced organizations and social movements. In the world, he is at the forefront of an intellectual avant-garde which demands to rethink everything. “Freire is not only a man of his time, but he is a man who belongs to the future, because he is a visionary and a supporter of his essence,” he said. Henri giroux. Today and as always, education is a permanent battleground where one argues, in Freire’s words, between “repeating the domesticated present” or “building a revolutionary future”.

In the prologue of Pedagogy of the oppressed, the Brazilian professor Ernani Maria Fiori wrote that “Paulo Freire’s method is, fundamentally, a method of popular culture; educates and politicizes. It does not absorb the political into the pedagogical, and education does not contradict politics. It distinguishes them, yes, but in the unity of the same movement in which man is historicized and seeks to find himself, that is to say, he seeks to be free ”. The last words Freire writes in this iconic book are, like any good revolutionary, of great hope: “If nothing remains of these pages, we hope that at least something will remain: our trust in the people.” Our faith in people and in creating a world in which it is less difficult to love ”.

KEEP READING

[ad_2]

Source link

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos