[ad_1]

It is a well known fact that French Revolution 1789 constitutes an episode of enormous historical importance and which has been regarded as such from its inception to the present day; we could say the same about Mexican revolution, which produced books of all kinds since it began to be produced until its completion. In both cases, factual investigations and interpretations of all kinds, fascinating, films and novels, biographies and studies. They are incorporated into national glory, presidents and teachers fill their mouths with mentioning them either to remember what they were and to falsify them. They have given rise to real libraries but despite the distance and the fate of their two protagonists and their immediate and distant consequences, institutional and rhetorical, they are also the object of new looks, they come back to them, it would seem that they constitute infinite deposits of importance. It gives the impression that to understand something more than what they contain light up the present provided that the present is not limited to the immediate. Incidentally, the technologizing mentality which dominates much of contemporary interpretation modes seems, only seems, to justify this confinement and to support the disdain of history.

I dare not say that a similar chance has russian revolution, which in post-Soviet Russia became a bad word, an unfortunate invocation, surprisingly because it was one that almost immediately emerged as triumphant, while others struggled to find its form until, d ‘somehow, barely glimpse, lose it.

It is possible that yes, that he has an equivalent presence to the others, the immense bibliography which appears in Deutscher’s trilogy on Trotsky would prove it, but, at a cursory glance, it seems that its historical significance, to except what is saved by the novel by Leonardo Padura whose narrative center is no less another, it is almost only the object of gazes and questions from irreducible followers or sworn enemies, denigrating and vulgar, without major historical interest, on characters, Lenin, Trotsky et al., And even on the fact himself, the revolution as an error and even as an unfortunate and criminal episode. Perhaps the resounding end of the Soviet Union and its Chinese or Korean or even Cuban transformations reduce its value or move away, it is as if it is only granted the value of a memory and not a thickness that is granted to others. A unique human and political experience is put aside and doomed to melancholy When in reality it produced an extremely complex agitation, it shook the system, reinterpreted mental structures and lifestyles, promised utopian futures, in short, it upset the balance which the bourgeoisie had achieved after centuries.

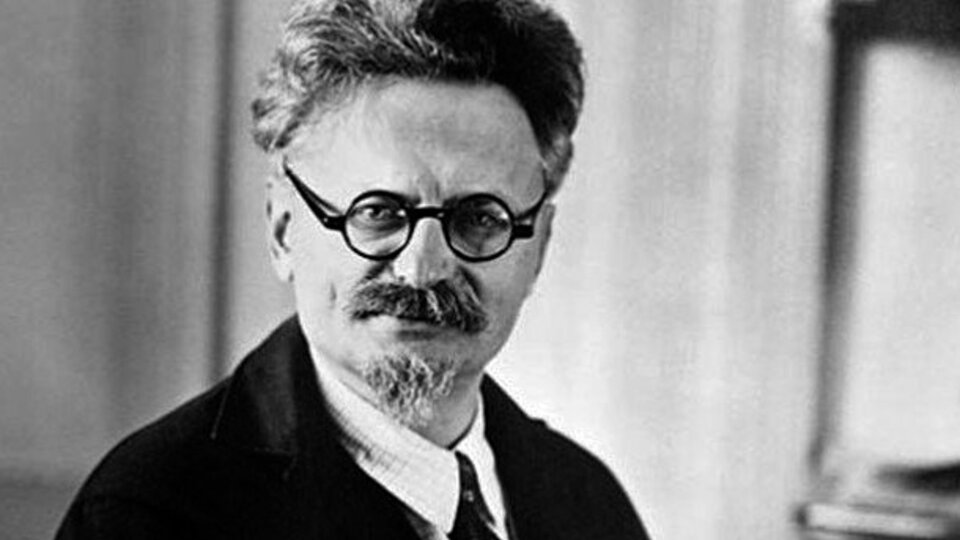

And although the “Russian Revolution” event was the central phenomenon, in its most dramatic moment, two figures stand out, Trotsky and Stalin, which in their confrontation become archetypes, coagulations of concepts inherent in civilization itself. One embodies the intellectual, universalist, even utopian, heir to the great European cultural traditions, brilliant builder, writer and unlimited orator of unparalleled strength but, victim and loser in the conflict, and the other, a cunning pragmatist, unscrupulous shadow concoctor. , implacable enemy, builder of power, manipulator of men and of speech, local and closed, winner with Pyrrhus in the competition. Basically, and without forcing analogies, two types that we find in the eternal conflict between thought and action, fundamental ends and immediate objectives, but, in this case, linked to an attempt at change which could have been decisive in the story. of humanity and that, at one point, it seemed.

The biography produced by Isaac Deutscher After careful research, in archives, in books, in memoirs and testimonies, in Soviet and European newspapers, he shows this conflict from its gestation to its tragic end. The facts that it recovers inform what is known but also what was not known and which blindly sheds light. Story of course, and as such based on direct and engaged knowledge as well as research, but also literature, narrative tension, character design, characters and conflict, in the most classic tradition of the art of history. It brings out a very attractive panorama of the central figure, his decisions, his mental patterns, his unusual interventions for his time and space, as well as, with the same pictorial vigor, the countless political processes of at least six decades. , the end of the 19th century and the middle of the 20th century and the “Revolution” as the creature born from the meeting of two aspects: the complex crisis of despotism and the nervous and tenacious intuitions of Lenin and Trotsky, the first architect of the revolution, the other executor, builder of an imposing building, nothing less than a new country limited by the old disproportionate canine business that was beginning to be conducted.

Trotsky, it’s about him, he’s the center and the trigger of this story and from their avatars arise multiple situations but, above all, characters presented as if they were the protagonists of a singular tragedy; in fact, going into the future, they all fell into the terrible category of an invented phrase I don’t know by whom who proclaims “The revolution devours its own children”It was therefore during the French, Mexican and Russian revolutions that this fateful fate could not be avoided, all its actors executed by the implacable Georgian.

It is very difficult in a few lines to evoke the quantity of themes presented by the three volumes, to consider them and to understand their projections, but we can underline that the trilogy invites at least two objectives of reading, information, c ‘ that is, to the past, and prospecting, to the future. If the first satisfies because it allows us to know, document and consider through, “what really happened” – I think now, but since the end of the war which ended in 1945 , we know, at least I, why Nazism liquidated in the hard decade of the 1930s to German Communism and why the communist language was stereotyped and nullified the most precious thing it possessed, utopia – the second worryingly, there are many lessons that can be learned to understand what happened next and continues to happen. Even in our own country: give in or resist, for example, an option that haunts our history until the present, and which may seem singularly and exclusively ours, is at the heart of what brought to the scaffold in Stalin’s time those who forged the Revolution and created the Soviet Union. Except Trotsky, moreover, who gave his life to what he had imagined and created but who did not give in.

The first volume, The armed prophet shows a fervor, that of possibility and construction, the second, The unarmed prophet, the difficulty of understanding, the third, The banished prophet, the heroism of survival. In each of them, each episode is always followed by intelligent interpretations, as of someone who was close but at the same time analyzed, judged, debated between success and error and showed the shortcomings of what had been presented as a thought. compact, well-founded and effective, that is to say, with a well understood and correctly considered Marxism, the goals of the revolution could have been achieved with resounding success.

For some, perhaps, the questions that reading can prompt are typical of bygone times, once the Soviet Union closed its doors and transformed what was once a thriving capitalist enterprise; for me, an entry into a history and a destination towards which it is very difficult to remain indifferent. As far as history is concerned, what I could modestly say is that what these books show “means” a lot about the twentieth century, it is sometimes the culmination of a long-standing process, marked by this harsh and happy expression, “the class struggle”. As for Trotsky’s fate, it is unique: in short, it was a question of “making history”.. In part, at least as a model, he succeeded, in part he fell victim to this spectacular goal; the drama is how he could be defeated politically and the paradox by who, but not in what that meant.

Deutscher’s work is not a tribute, there is no reverence; there is examination, there is evaluation, there is distance but intellectual respect: precisely what Stalin and his extensions blocked, by lies, silences, repressions, death, in a curious – odious – interpretation of what Marx formulated at the time and which guided and oriented a large part of humanity for almost two centuries.

* About the Isaac Deutscher trilogy (The armed prophet, the unarmed prophet Yes The banished prophet), published in 1954 by Oxford University Press, New York / London and in a Spanish translation by José Luis González in 1966, in Mexico, Ediciones Era. In Chile, an edition, which takes up the era, from 2007 and another from 2014, by LOM Ediciones. Finally in Buenos Aires, in 2020, the same, by IPS Ediciones.

.

[ad_2]

Source link

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos