[ad_1]

From the public, special to Página / 12

The emergence of new variants of the virus was almost inevitable. When viruses multiply, mutations can occur. And with him coronavirus multiplying in the cells of millions of people around the world, it was only a matter of time before we had to face new variants.

A new variant of the virus could, in theory, present one of these 3 possible problems:

- That the new variant be transmitted from person to person more efficiently. This appears to be the case with the British variant.

- That the new variant causes more serious illness. Fortunately, the variants detected so far do not appear to exhibit this problem.

- That the new variant is resistant to the vaccines developed and must be updated.

Now let’s focus on this third problem, because a study (not yet published) on the South African variant indicates that it may be quite resistant to vaccines developed for the “parent virus”.

Let us first remember what a variant of the virus is

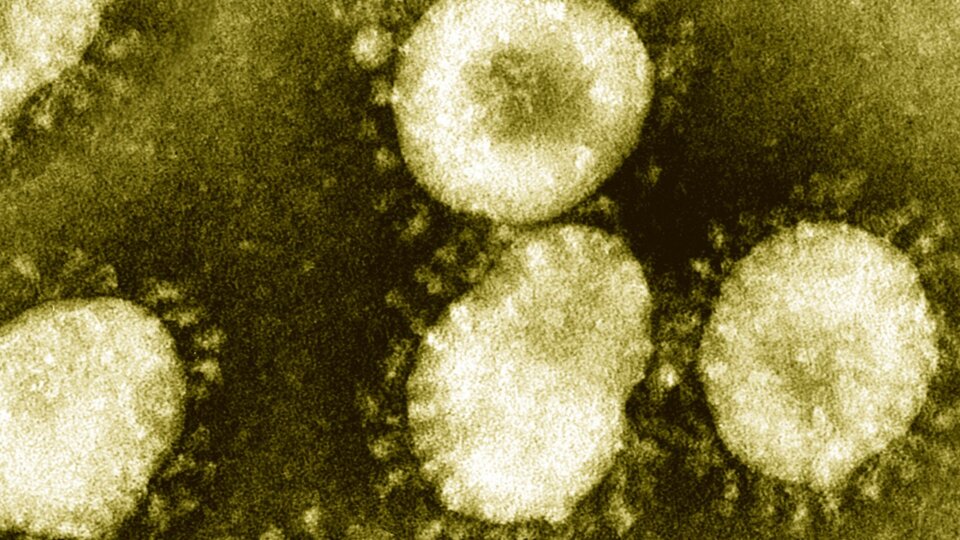

Just like humans have DNA, the coronavirus also has its genetic material. In the case of the virus, it is called RNA.

This genetic material is the virus’ “instruction manual” for reproducing itself.

Coronavirus RNA is made up of 30,000 letters. It starts like this (in this case translated to DNA):

… and so on until all 30,000 letters are completed.

By multiplying, the virus sometimes makes a mistake and changes one letter for another. For example: replace a letter “g” with a letter “u”. The other 29,999 letters remain the same, there is only one letter difference. This is called a mutation.

The new virus with this mutation will be a little different to the old virus.

Several mutations can accumulate and will appear “varieties” virus that will be more than one letter different from the original virus.

What are the main varieties circulating in the world?

- The “UK variant” (technically called B.1.1.7). It was detected in October 2020 and spread very rapidly to London and southern England and is present in many European countries (including Spain).

- The “Brazilian variant” (technically called P.1). First detected in January 2021 at Tokyo airport among travelers from Brazil.

- The “South African variant” (technically called 501Y.V2). First detected late last year in South Africa and has been detected in at least 20 countries.

These variants are surely circulating in more countries than what has been detected.

Let’s say someone tests positive on a PCR. It means you have the virus, but it doesn’t tell us what variety of virus you have.

To know the variety of the virus, you have to read all the letters of the RNA. This is called “virus sequencing” of patients.

But a very small percentage of the positives are sequenced (this percentage varies by country), so the new variants could be circulating in more countries than we realize.

Let’s move on to the South African variant. What is special?

The South African variant has 9 RNA letter changes that describe how to build the backbone of the virus.

Mutations in the spine of the virus are the ones that worry scientists the most, as the spine is what the virus uses to get into our cells.

And more importantly: the antibodies that our bodies make against the virus are attached to the spine of the virus. If the spine changes too much in the new variant, the antibodies that work against one variant may not work against the other.

How do researchers determine whether or not antibodies to the original virus work against the variant?

The procedure is as follows:

1.- They take the serum of patients who suffered from covid months ago. These patients have been infected with the parent virus and have antibodies against the parent virus.

2.- They put these samples with antibodies in contact with the virus of the new variant and observe whether they also block the new virus.

In almost half of patients (21 of 44), plasma containing antibodies to the original virus does not block the new variant of the virus.

Is this result final? So the current vaccines do not work against the South African variant?

No, this is not a final result. It is worrying, but not definitive.

1.- This is a study that has not yet been reviewed or repeated by other groups.

2.- As we explained yesterday, immunity against the virus does not depend solely on antibodies. There are other parts of the immune system such as T cells which surely play an important role as well.

Let’s put ourselves in the worst-case scenario: let’s assume that current vaccines don’t work against this variant. Would changing current vaccines be expensive?

Here’s the best news: The vaccines in use today are technology that makes them easy to change.

In traditional vaccines (inactivated, attenuated or protein), the design and production process is very complex.

Current vaccines based on messenger RNA, which is introduced into the body are directly “the letters” of a part of the virus. It would therefore suffice to replace the letters by those of the new variant to have a vaccine.

.

[ad_2]

Source link

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos