[ad_1]

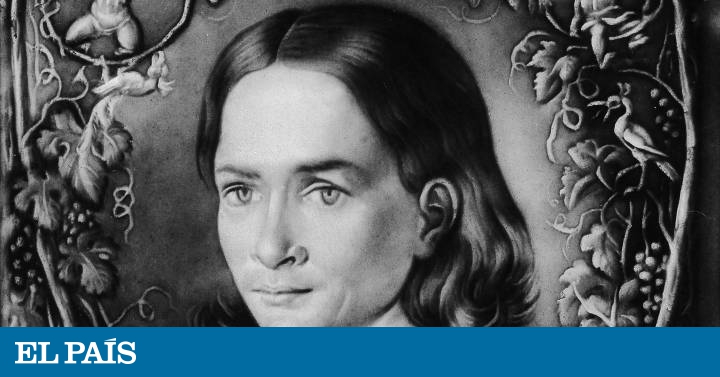

Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge He was one of the few pharmacists to have had a double doctorate in the nineteenth century. His determination to study, together with a good deal of luck in some of his discoveries, earned him a special place in the history of pharmacy and chemistry with discoveries such as caffeine alkaloid, aniline, phenol, quinine, pyrrole, atropine, tar dyes and chromatography.

Despite the large number of discoveries made, it highlights the caffeine, its importance and the carelessness of which it has occurred. It can also be the most universal, after providing a scientific explanation for the habit of drinking coffee to activate in the morning. And today, whoever says coffee also says a cola with the same ingredient.

Of humble origin, Runge, with an iron faith in himself, wanted to study at any cost. Soon he opted for the pharmacy and from there went on to chemistry. From an oversight of his experiences, he discovered how to dilate the student with a drop of belladonna and a chance encounter with Goethe, the challenge of badyzing coffee beans and discovering caffeine. Despite his career in scientific success, he survived as best as he could in the last years of his life, frustrated that no one ever paid attention to his proposals to make economic profit from his discoveries.

Runge He was born that day, today, February 8, 1794. He was the third son of a Lutheran pastor from Billwerder, near Hamburg. After attending primary school in Schiffbeck, the small Runge chose the profession of pharmacist, which allowed him to quickly earn his own money. In just 20 years, he discovers the mydriatic effect produced by belladonna.

In October 1816, Runge enrolled in medicine at the University of Berlin. Two years later, he continued his studies in Göttingen, where he did an internship in chemistry. He moved to Jena and, a year later, in 1819, he obtained his doctorate in physics with a botanical work on intoxication by belladonna and henbane.

His chemistry teacher, Döbereiner, invited Goethe to see how Runge could change the eyes of cats with the extract of belladonna. Runge, still too young, seemed nervous, with a borrowed tuxedo and a cat in his arms. Goethe was surprised to notice the difference between the cat's pupils and, impressed, gave him a box of coffee beans and asked him to badyze them chemically. In 1820, he also discovered caffeine.

He returned to Berlin in 1819 to become a university professor. There, he lived with pharmacist and physics professor Johann Christian Poggendorf, transforming his bachelor house into a laboratory with all sorts of experiences. Runge's is devoted to a doctoral dissertation in which he treated indigo dye and its compounds with metal salts and metal oxides.

He also wrote his book Recent phytochemical discoveries to establish scientific phytochemistry and he started giving clbades on plant chemistry and technique. In 1823, he undertook a trip to Paris, then the great research center in chemistry, to complete his studies. On his return, he went to Wroclaw (which was now part of Prussia, but was then Polish), although there was little, as he made another trip to Germany. , Switzerland, France, England and Holland.

In 1828, at the age of 33, he became badociate professor at the faculty of philosophy of the University of Wroclaw, but without a fixed salary. To devote himself more to the practical application of chemistry, he left the university in 1831. A year later, he badumed the technical management of a chemical factory in Oranienburg funded by the Prussian state. A year later, in the summer of 1833, he produced phenol and aniline by distilling coal tar.

Runge was well aware of the potential use of dyes discovered from tar, but the factory sales manager was unaware of all his industrial proposals. His experiments on measuring color intensity by performing so-called spot reactions on filter paper are closely related to his research on tinting dyes.

In 1850, the state bought the factory and two years later, Runge was fired for being accused of spending little time at work. It is true that he wrote at least seven books during this period. With a miserable pension which, after a while, he stopped paying, started to live in bad conditions and fell into oblivion.

However, his pbadion for research was always stronger and he remained oriented towards practical chemistry, devoting himself to the production of artificial fertilizers and the writing of books, especially his famous Maintenance letters, in which he gave advice on how to eliminate the smell of cutlery from herring, on removing rust stains from clothing, on how to marinate meat or making fruit wine. Recipes that became very popular at this time and have reached our days. But farmers also received advice on disinfecting cow treatment plants with bleaching powder (lime chloride) and pharmacists were able to detect the sugar in the urine.

The fields of work of Runge they have always been plant chemistry and tar-based dye, although they have also excelled in inorganic chemistry. In 1862, 28 years after the discovery of coal tar dyes, he was honored at the London Industrial Congress and was eventually recognized in Berlin.

Runge, who never married, dies at his home in Oranienburg on March 25, 1867 at the age of 72 and is buried in the city cemetery. His great scientific work contrasts with the limited repercussion of his discoveries in life, though his legacy has placed him among the most remarkable chemists in modern history.

You can follow The material on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or subscribe here to our newsletter

.

[ad_2]

Source link

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos