[ad_1]

The political crisis in Venezuela faced the US with a dictator who refuses to leave the presidency. But the crisis has a broader meaning: it shows that Latin America has once again become the stage on which the great rival powers struggle to gain influence and advantages. USA It faces a new wave of geopolitical competition around the world and is under pressure in its own garden.

The region has already been at the center of global competition, of course, of rivalry between Spain and Portugal in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries up to the Cold War between Washington and Moscow. However, after the fall of the Soviet Union, Latin America seemed, at least for a time, to become a geopolitically free zone. The withdrawal and disintegration of the Soviet Union left the United States without adversary because of the predominant regional influence. Cuba de Castro has been locked in a deep economic crisis. As countries democratized and opened up to free markets, the region also became unipolar in the ideological sense.

However, in the early years 2000, time was changing. First, a generation of leaders who viewed the neoliberal economy as the source of constant poverty and inequality in the region. Governments led by prominent figures such as Chávez in Venezuela, Evo Morales in Bolivia and Rafael Correa in Ecuador have badociated attractive populist politicians with programs that encourage illiteracy and, in some cases, authoritarianism. They challenged the United States diplomatically and rhetorically and established close relations with Cuba. This created a block of regional actors opposed to US power – as external actors began to exert their own influence in the region.

Pope Francis and bridges in Venezuela

The Chinese economy has flourished over the last two decades and its presence in Latin America has also developed. Trade and Investment China has emerged almost everywhere, not just in countries run by radical populists. Chinese trade and loans have helped illiberal leaders like Chávez and Maduro by reducing their vulnerability to US pressure. and from the west. Then come the military engagement, raising fears that Beijing may try to establish a strategic position in the Western Hemisphere. Although some aspects of relations between China and Latin American countries remain controversial – some Chinese infrastructure projects have been criticized because they generally go to China and not to Latin-American workers. Americans, for example, Beijing has undoubtedly become a player in the hemisphere. Western

Russia has offered economic and diplomatic support to Chavez, Maduro and other autocratic leaders such as Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua. He sold populist governments jets, tanks and other weapons and resumed oil deliveries to Cuba as well as delivery of military technology. To the great concern of the United States, the Kremlin has also worked to establish a significant intelligence presence in Nicaragua. As described by Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, "Moscow's approach to Latin America today echoes Soviet support between 1960 and 1980".

The Russia's and China's relations with Latin American countries are often described as mere transactions, and it is true that Moscow and Beijing can strengthen the support of big companies. Russia's continued support of the Maduro regime has been rewarded by significant participation in the Venezuelan oil industry. China has also considered Venezuela as a source of energy and its economic growth would have led to increased participation in Latin America, even in the absence of any geopolitical project.

But for both countries, this participation also has a deeply competitive logic. Arriving in Latin America is a way to keep the US in an imbalance, exerting influence on Washington's "near abroad". This helps to increase the influence and world stature of Beijing and Moscow at a time of intensifying rivalry with Washington. Finally, supporting autocratic regimes such as those of Caracas and Managua, whether in silence, as in the case of China, or more verbally, as in Russia, is also a way to ensure that the world remains safe on the ideological plan. authoritarianism in Beijing and Moscow.

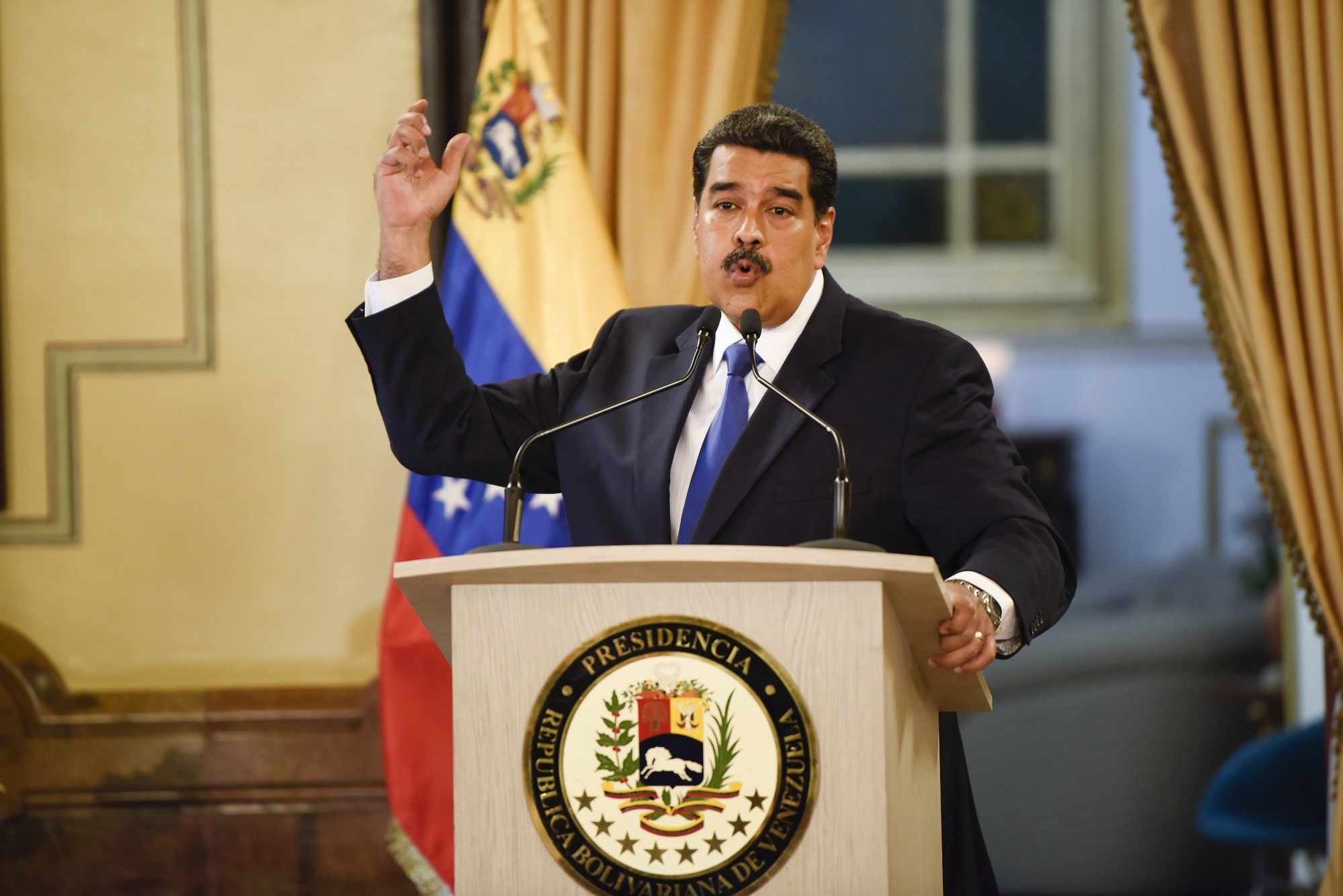

All this constitutes the backdrop of the Venezuelan crisis. The rise of Russian and Chinese influences in Latin America in general, and in Venezuela in particular, is one of the main reasons why the Trump government has adopted the banner of human rights and human rights. democracy in an unprecedented way. By imposing harsh economic sanctions, asking the army to abandon Maduro and supporting the political opposition led by Juan Guaidó, the Trump government is trying to deprive Moscow, Beijing and Havana of the lack of security. an essential partner in Latin America. And while Russia and China have reacted very differently to this crisis, the two countries are working, in their own way, to protect this partner.

The Chinese government has expressed opposition to the international campaign against the Maduro government; He continued to recognize his besieged government even when dozens of democratic countries supported Guaidó. Russia has been much tougher in denouncing Washington for attempting to "devise a coup", in the words of its UN representative. He warned against US military intervention and symbolically sent two strategic bombers with nuclear capabilities to Venezuela. Specifically, Moscow sent 400 mercenaries to strengthen Maduro's Praetorian Guard and pledged to provide additional economic support. Therefore, there is some sense of the cold war in the current crisis, with the United States and its rivals aligned on both sides of a conflict over who should govern a key country of America Latin.

There is no doubt that the Moscow position has an element of disappointment. It can only project a very limited military power in Venezuela or in any other part of Latin America. However, by providing Maduro with moral and material support that it would not otherwise, both Russia and China are making the current crisis more difficult to resolve.

Is America ready? for this new environment in which local crises and global tensions interact again in a stimulating way? The Trump administration deserves a credit here. He spoke frankly about the dangers of Chinese and Russian influence for Latin America and the United States. He has also worked closely with other Latin American governments – including Brazil's new president, Jair Bolsonaro – to coordinate the diplomatic lobbying campaign against Maduro.

There are also less useful trends in American politics. Trump's earlier hostility to the NAFTA had prompted Mexico and other Latin American countries to diversify their economic relations, with China being a prime target. The government has been cautious about the threats posed by Chinese investments, without specifying clearly where Latin American countries should turn to resources.

Then comes the President's offensive remarks about people of Hispanic descent who have not attracted the Latin American public. In a survey conducted in 2015 by the Pew Research Center, 66% of Latin Americans from seven different countries perceived the United States on average. positively Under Trump, this number dropped to 47%. Finally, developing a comprehensive strategy for managing the influence of China and Russia will require coherent policies and privileged relationships – talents that this administration has rarely demonstrated.

Washington is waking up closer and closer to the new struggle for an advantage in Latin America. The result in Venezuela will be a first indicator that will indicate whether US policy is on the job.

.

[ad_2]

Source link

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos