[ad_1]

Until the discomfort is too much.

“I felt a huge burn in my stomach. He needed medical treatment, a specialist. He also had breathing problems, ”said the Peruvian, who was finally admitted to Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan in 2011.

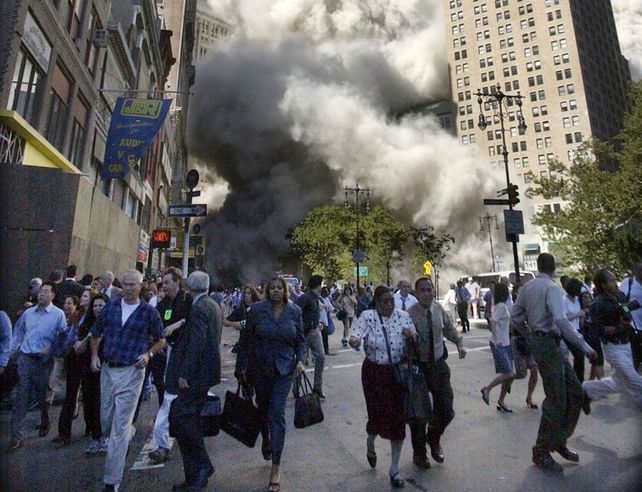

Anchahua and other Hispanic immigrants who cleaned up the area around the Twin Towers have for years sought legal immigrant status in the United States in compensation for the hard work and health issues they suffered.

Two decades after the attack, however, only a few dozen are still participating in the protests. Others have given up on the fight.

“It is difficult to find work here without immigration status,” Anchahua said. “The lawyers who helped us a long time ago told us that our papers would reach us, but look, 20 years later and we have nothing,” the Peruvian told The Associated Press.

These migrants are not as visible as the police and firefighters who worked in the so-called ‘ground zero’. While some say they feel forgotten by the US government, others have returned to Latin America.

Informally hired by large cleaning companies, they cleaned up dust and debris without proper protective gear. Some are struggling to cope with how the disaster changed their lives, and many are being treated for anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Some are holding a protest in October in an effort to pressure the government to establish a legal residency route for those who have been cleaning up lower Manhattan for months.

Former Congressman Joseph Crowley, who represented part of Queens in Washington, announced a bill in 2017 to allow these workers to obtain legal immigration status in the United States. His office estimated at the time that between 1,000 and 2,000 workers would be covered.

The bill, however, was never passed.

Lauren Hitt, spokeswoman for MP Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez who defeated Crowley electorally in 2018, told the PA that her office was “actively” exploring the possibility of reintroducing the bill into parliament.

“The MP also supports comprehensive immigration reform and has proposed with others many bills that would have paved the way for citizenship for these workers and others,” Hitt said.

While many of the workers who cleaned up lower Manhattan in 2001 are Latin Americans, others came from Poland and other European countries. Workers organized themselves into different groups to share information on medical aid and financial compensation.

Rosa Bramble Caballero, a Registered Clinical Social Work Psychotherapist, has assisted these workers for 15 years, first working with state and local programs to offer assistance, and then on a voluntary basis, organizing meetings in the basement. from his office in Queens.

Dozens of workers who cleaned up lower Manhattan meet there to chat, eat cheese and chicken patties, and drink coffee together.

“It became a space for them to feel safe, to talk about their life, what they needed and most of all this mutual support, not to feel alone,” said Bramble Caballero.

Lucelly Gil, a 65-year-old Colombian, missed few of these meetings. She received financial compensation from the Federal Victims Fund after developing breast cancer. She is currently on medication for rhinitis and gastritis, uses an asthma inhaler and is being treated for depression.

Gil spent six months cleaning up the dust in Lower Manhattan, in government offices, banks, and restaurants. He charged about $ 60 for every eight hours he worked.

The Colombian said she suffered from nightmares for a long time after seeing emergency personnel take body parts away. He still remembers coughing while working and a rash on his skin when the insulation had to be removed from the walls.

“To us who are cleaning, instead of helping us, they could at least have given us the papers,” Gil said. “The Americans weren’t cleaning there. Poor us Latinos who saw the consequences later ”.

So far, more than 112,000 people have signed up for the federal World Trade Center health program, which offers free medical assistance to people who can prove they have been exposed to dust from the Twin Towers. The program does not apply for immigrant status.

Many of those who sign up have minor or controllable illnesses, such as heartburn, chronic sinus problems, or asthma, which are common in the general population and which may or may not be related to heart attacks. September 11th. Others suffer from more serious illnesses or conditions that are rare for their age.

Joan Reibman, medical director of the World Trade Center Environmental Health Center, which has treated immigrants who cleaned up lower Manhattan for years, said many of them suffer from significant reduction in lung function, digestive and post-traumatic stress disorder.

“They were exposed to terrible scenes during those days,” Reibman said.

Migrant workers face and face certain obstacles when seeking medical care: they lack economic power and generally do not belong to unions, the expert said.

“A lot of them didn’t know about these programs because they weren’t connected in the same way as other workers. Many didn’t speak English either, ”Reibman said.

About 800 immigrants who cleaned in Lower Manhattan are treated by the Reibman Center.

About four years ago, Anchahua, the Peruvian immigrant, received about $ 52,000 in damages after filing a lawsuit against the cleaning company he worked for in 2001.

Last year he went to Peru to help his elderly mother and a sick brother. However, he decided to return to New York this year after not finding a job in his country and wishing to continue his medical treatment in New York. He applied to the US government for a humanitarian visa, which he was denied. He then illegally crossed the US-Mexico border last month.

Luis Soriano, another worker who cleaned in lower Manhattan, also returned to Latin America but did not return to New York.

“I completely came to see my mother and liked her even though she was about three years old (before she died). And I felt in poor health, ”said Soriano, who spoke by phone from Ecuador.

The 59-year-old worker did a cleaning job around Fulton Street for about three months. He says he still has trouble breathing sometimes.

“I get tired, I get angry. I had to undergo treatment but since I arrived here I have stopped doing the treatment, ”he said.

“We need them to remember us (…) the immigrants we brought to this country,” he added. “And we have worked, we have fought and we have already aged.”

By CLAUDIA TORRENS / Associated Press / NEW YORK

[ad_2]

Source link

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos