/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/QLNPTHNZK2JUMNJEIME6MSHAIA.jpg)

[ad_1]

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/QLNPTHNZK2JUMNJEIME6MSHAIA.jpg)

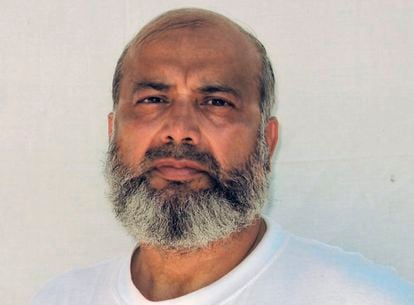

With the victory that brought him to the White House, Joe Biden inherited an open wound to American justice and human rights, albeit virtually forgotten by public opinion. After almost 20 years, the affront to Guantanamo prison in Cuba has passed through three different administrations. Now it is approved by the government of Joe Biden, which has given its approval for three detainees who remain in the military naval base that the United States has on the island to be transferred to countries that promise to impose measures of security. One of the three is the oldest prisoner in the prison, Pakistani Saifullah Paracha, 73, who spent 16 years in US detention. The other two detainees are Abdul Rabbani (54 year old Pakistani) and Uthman Abdul al-Rahim Uthman (40 year old Yemeni); both have been held by the US military for two decades. None of the three have ever been charged with any crime by the United States.

Guantánamo was designed nearly 20 years ago, in January 2002, to prevent so-called “enemy combatants” captured in the George W. Bush administration’s war on terror after 9/11 from being subject to US law. The White House therefore used a legal trick: by locating the prison on the Caribbean island, the center was outside the Geneva Convention, which protects prisoners of war, and did not require the application of the guarantee of ‘habeas corpus – right to appear before a judge at a specific time – some prisoners he held outside the world and outside the jurisdiction of the United States At the time of the greatest occupation, Guantánamo numbered 779 people. Before leaving the White House, Bush transferred some 550 prisoners to other countries. His successor in power, Democrat Barack Obama, did the same with about 200 people.

Donald Trump promised during the 2016 election campaign that he would once again fill Guantanamo’s cells with “bad guys”. A promise that was never kept but, on the contrary, a man left the center who admitted to having belonged to Al-Qaeda and who was sent to Saudi Arabia to be rehabilitated in a center for jihadists. Today, only 40 prisoners remain in what President Obama has called “a stain on America’s national honor.”

Of those 40 detainees, more than 10 have been charged with war crimes by the controversial military courts established in Guantánamo – which elude American justice – and five others are the coordinators of the 9/11 attacks, including the mastermind of the attack., Khalid Saij Mohamed, as established in the Congress report on 9/11.

The day after he was sworn in, in January 2009, Obama promised to shut down Guantanamo within a year. At the end of his term, the Democrat claimed that the existence of the detention center on Cuban territory was contrary to American values, harmed national security and was expensive. “This is about closing a chapter in our history,” Obama said in 2016.

It was pure rhetoric. The Capitol declared Obama’s goal dead. The then Senate Majority Leader, Republican Mitch McConnell, categorically stated that “under US law it would be illegal to transfer prisoners from Guantanamo to national territory,” he said. It was of little or no use that Obama looked to his incumbent predecessor, George W. Bush, to support his drive to shut down the center, arguing that the man who designed the architecture around Guantánamo (detentions without charge , military commission, foreign territory to circumvent American law) also wanted its closure at the end of his presidency.

Obama gave up

After his re-election as President of the United States in 2012, Obama made no mention of Guantanamo in either his inaugural address in January or his State of the Union address in February, a clear sign of surrender.

The closure of the detention camp seems doomed to failure. Mainly for a legal problem. Because even if there was a green light from Congress to transfer prisoners to maximum security prisons in the United States, any judge or court that proposed it could challenge the legality of the detention and the confessions made by the Guantanamo detainees. , marred by torture. . Inmates at the center risked their lives with hunger strikes and, in some cases, even hanged themselves without hoping to be released. A few years ago, Carlos Warner, the defense lawyer for 11 of these prisoners, told this newspaper: “The only way out of Guantánamo is to die.”

Subscribe here to bulletin of EL PAÍS América and receive all the informative keys of the current situation in the region.

Source link

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos