[ad_1]

Do climate change and global warming exist? Yes, are they a risk for humanity? Yes, if they present a risk, do they threaten economic activity? Yes, do central banks need to assess the strength of each bank by checking whether they are lending their money to activities likely to be affected by climate change? The answer is also "yes".

Yesterday, at a forum in Washington, the US capital, IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, felt that it was inevitable that central banks would begin to intervene in this matter. "Climate disasters are clearly a risk, and if this risk is greater, it must be taken into account," he said. But it went further: he said that climate risk levels would be integrated into IMF country assessments.

The question is not a joke: in the future, for example, the Argentine governments will ask for the umpteenth time that the Fund will provide them with help not only to find recommendations regarding two classics of all time, such as pension system or labor law. but also with commitments to establish or levy taxes on greenhouse gas emitting activities or to respect the emission ceilings applicable to these gases, to give two hypothetical examples.

These policies will infiltrate the economy as a whole. Philip Lane, one of the executive directors of the European Central Bank, has of course taken into account the impact of climate change on credit activity. "It's a structural change: they are already altering household spending, business plans, energy prices … and of course banks." In this logic, for example, a bank that lends money to build houses on the coast of the sea could be considered riskier and, therefore, it could stop lending money for it or impose a higher interest rate, which would discourage these developments.

Dead cow, living cow

For Argentina, the problem will be crucial, even if it is difficult for us to see it. It is natural: our country is still dealing with a state and a central bank unable to provide an essential public good as a stable currency, while in the rest of the world, inflation seems to have been passed on to museums. Who will worry about climate risks?

However, we had better do it. The most competitive, dynamic and potential sectors of the Argentine economy are subject to severe and growing environmental monitoring: food production (especially livestock, bombarded by misleading propaganda on methane emissions); the extraction of hydrocarbons (in particular the Vaca Muerta, which adds to the problems of fracturing); Mines and fishing.

Being left behind is not free. We can engage (for example against the medieval environmentalism that criminalizes agrochemicals), but we do not have the power to change this state of affairs. Argentina urgently needs to establish credible institutions, in line with international standards, to certify the environmental performance of companies and sectors. It needs to put in place systems that allow the own activities to take advantage of this condition. These are only examples.

Green Bond and carbon tax

In the world, the train has already begun. Yesterday, Giorgeva said very clearly that the international financial institution was moving towards an increase in pollution control activities: "If the price of carbon is not high enough, there will be no economic transformation."

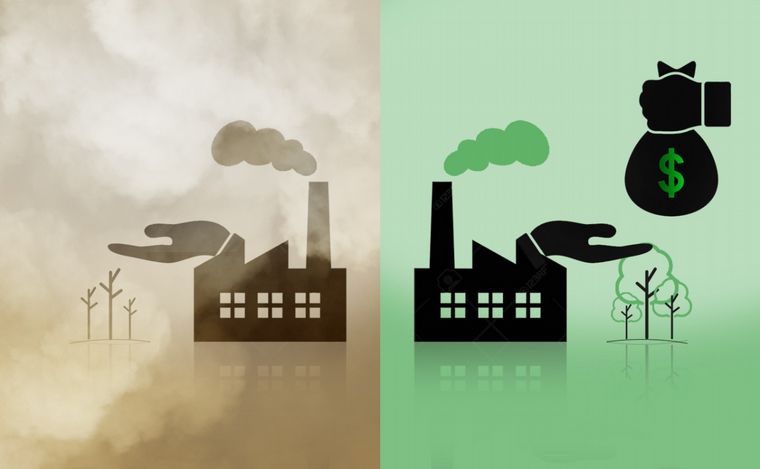

This, which is now advancing with carbon taxes and the green bond system, could add to an overall increase in credit for "dirty" activities.

Green bonds are issued on a market established in the Paris agreements. Very schematically: in this market, the countries that have made the most progress in this commitment are allowed to emit a decreasing amount of tonnes of carbon dioxide (or their equivalent in other greenhouse gases such as methane) over time . Each country then allocates these quotas between economic sectors and companies. Companies that issue more than authorized must cover the difference by buying bonds. And who do they buy from? Companies that, by investing in own energy and activities, are allowed to issue these bonds. Thus, dirty people must be cleaned (to save the cost of obligations) and clean people find funding.

Carbon taxes are another incentive for the economy to turn from brown to green. For example, the one that Argentina has recently created by changing one of the many fuel taxes, which now rests on the gas emissions that it generates. It was a way to start respecting the Paris agreements.

Four countries of Latin America

There are already 46 countries and 28 subnational jurisdictions (provinces, municipalities, etc.) that have implemented these two methods to set a price on carbon and compel it to pay its emitters. Prices vary a lot. A World Bank study shows that in Sweden, the emission of one tonne of carbon dioxide costs 127 dollars. In Argentina, only $ 6 (and only concerns fossil fuels).

The World Bank estimates that a tonne of dioxide should cost between $ 40 and $ 80 for next year, so that emissions can be reduced to the levels set by the Paris Agreement.

Miss a lot. And not so much because countries like Argentina are very far from this amount, but because most countries have not even begun to punish the problem. In all of Latin America, only Mexico, Colombia, Chile and Argentina have entered the corral. The others whistle softly.

.

[ad_2]

Source link

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos

Naaju Breaking News, Live Updates, Latest Headlines, Viral News, Top Stories, Trending Topics, Videos