[ad_1]

A dolphin swims at an exhibition at the National Aquarium. The aquarium hopes to move its dolphins to a sanctuary off the coast of Florida or the Caribbean.

Claire Harbage / NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Claire Harbage / NPR

A dolphin swims at an exhibition at the National Aquarium. The aquarium hopes to move its dolphins to a sanctuary off the coast of Florida or the Caribbean.

Claire Harbage / NPR

Three years ago, the Baltimore National Aquarium made a big announcement. After a public reaction against marine animal parks caused by the documentary Blackfish, the aquarium decided to move its group of dolphins in a unique sanctuary.

They set a 2020 deadline to find the perfect location off the coast of Florida or the Caribbean – a place where the water is warm, the area protected and the climate calm.

But now, this decision for 2020 is no longer realistic, according to John Racanelli, CEO of the aquarium. And this is largely due to a factor beyond his control: climate change.

The more than 50 sites studied by the aquarium have not yet been deemed sufficiently safe with regard to the violent storms and the proliferation of algae, which should worsen with the rise in temperatures.

The umbrellas located near the dolphin aquaria of the National Aquarium aim to prepare animals for life that will follow in an open air sanctuary.

Claire Harbage / NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Claire Harbage / NPR

The umbrellas located near the dolphin aquaria of the National Aquarium aim to prepare animals for life that will follow in an open air sanctuary.

Claire Harbage / NPR

"There are big things you simply can not predict," says Leigh Clayton, Vice President of Animal Care and Welfare at the Aquarium. "We are looking at the precedents, how often are areas affected by hurricanes, where hurricanes tend to land, what were the historical damages?"

"The reality is we really do not know," says Clayton. "We are all understanding this."

And this is not just a problem for the dolphins of the aquarium. Below the dolphin arena is the turtle rehabilitation center, essentially a triage site for the so-called "cold-stunned" turtles. They are sea turtles that were suddenly exposed to such cold water that their systems actually died out.

The aquarium has seen more and more of these sick turtles over the years. According to Racanelli, as the waters warm up, sea turtles venture further north and find themselves in areas of brutal cold. Sea turtles following the Gulf Stream, for example, now find themselves trapped in the Cape Cod hook, which is causing most of the turtles recovering from the aquarium.

The aquarium saves sea turtles that get stuck and injure themselves in and around Cape Cod, Mass.

Claire Harbage / NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Claire Harbage / NPR

The aquarium saves sea turtles that get stuck and injure themselves in and around Cape Cod, Mass.

Claire Harbage / NPR

Apart from the aquarium, climate change has introduced a completely separate set of challenges for Racanelli and his staff. Due to its prime location in the Baltimore Inner Harbor, the aquarium is expected to face near-daily flooding by the end of the century. Last year, the city filed a lawsuit against 26 fossil fuel companies seeking compensation for the effects of climate change, including rising sea levels and storm surges.

The problems facing the aquarium – and the city at large – add to the myriad ways in which climate change is redefining life in communities across the country. As part of a series of lectures on how Americans have begun to adapt, NPR travels the east coast. Miami residents worried about the impact of climate on gentrification. doctors worried about global warming for their patients; and developers and homeowners who are increasingly focusing on protection from rising water

The aquarium is among the owners who evaluate the future of their building. To cope with the rise in sea level, they built a prototype floating wetland located in the harbor and designed to help protect against storm surges.

The aquarium has built a prototype floating wetland in the port on the outside of the building, designed to help protect against storm surges.

Claire Harbage / NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Claire Harbage / NPR

The aquarium has built a prototype floating wetland in the port on the outside of the building, designed to help protect against storm surges.

Claire Harbage / NPR

The 400 square foot vegetation plot is also designed taking into account the local ecosystem. The built-in hoses help to aerate the water, and aquarium officials say it provides better habitat for animals than other flood mitigation tools, such as dykes in concrete.

"What we really want is diversity, and wetlands do," said Charmaine Dahlenburg, director of field conservation at the National Aquarium. "There are micro-habitats, so there will be different types of animals that stop," she says.

The aquarium hopes to raise enough money to deploy 14,000 square feet of floating wetlands, including docks so visitors can see them up close.

The aquarium receives over a million visitors each year, which, according to Racanelli, provides them with a unique platform for interacting with and informing customers.

"It has become an emerging role for aquariums across the country and around the world to help people better understand some of the big problems we face," he said.

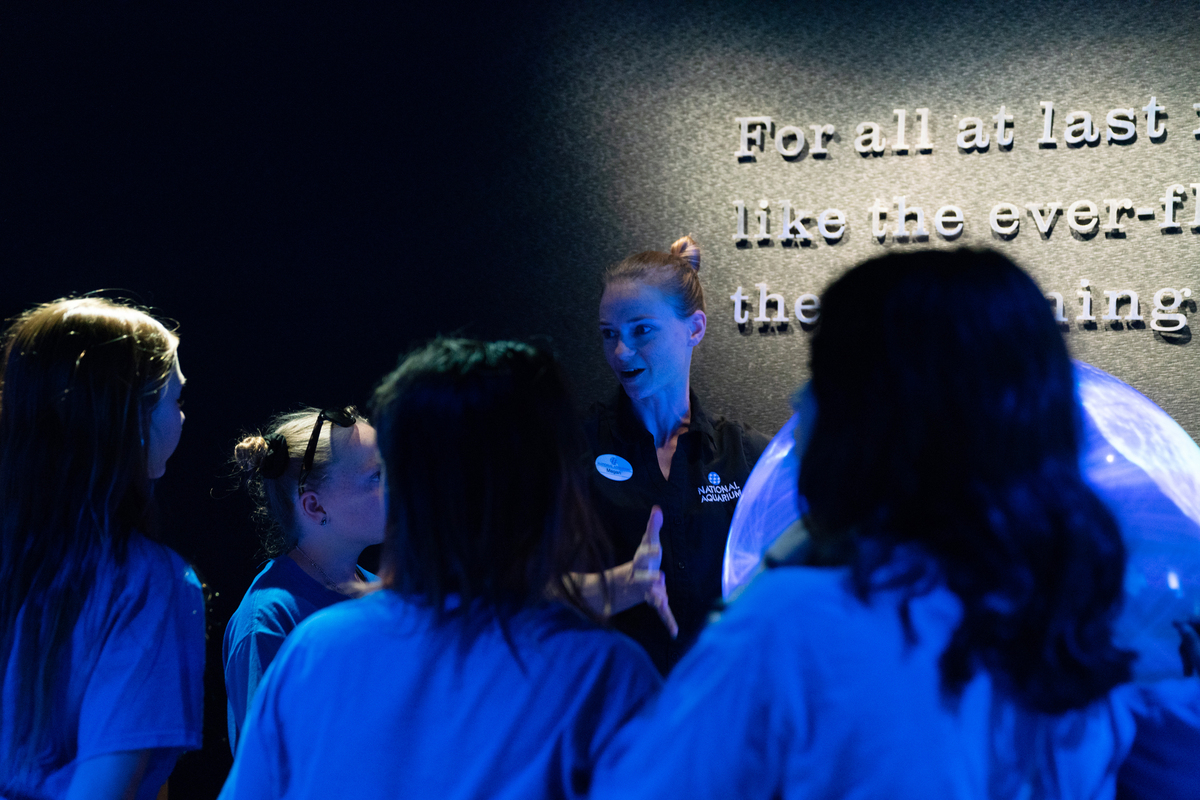

Museum teachers explicitly discuss climate change with visitors and ways to reduce their impact on the environment.

"It's not an imminent threat, it's a current reality," Racanelli said. "It's about where we're setting up our dolphin sanctuary or how we're moving here in our inner harbor in Baltimore … we can take action that we need not before but now. "

Visitors watch creatures swim inside the aquarium, including Calypso, a three-legged green turtle.

Claire Harbage / NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Claire Harbage / NPR

Visitors watch creatures swim inside the aquarium, including Calypso, a three-legged green turtle.

Claire Harbage / NPR

[ad_2]

Source link