[ad_1]

Tears are common in a fertility clinic. Tears of joy, tears of frustration, tears of loss occur almost every day. For some, these tears are the tears of "and if". What if I tried to get pregnant sooner? What if I knew then what I know now?

Hope is the incredible gift that Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe, the pioneers who made in vitro fertilization (IVF) possible, gave to the generations who followed them. They continued the experiments, even though the company feared that the "test-tube babies" would exceed the limits they never wanted.

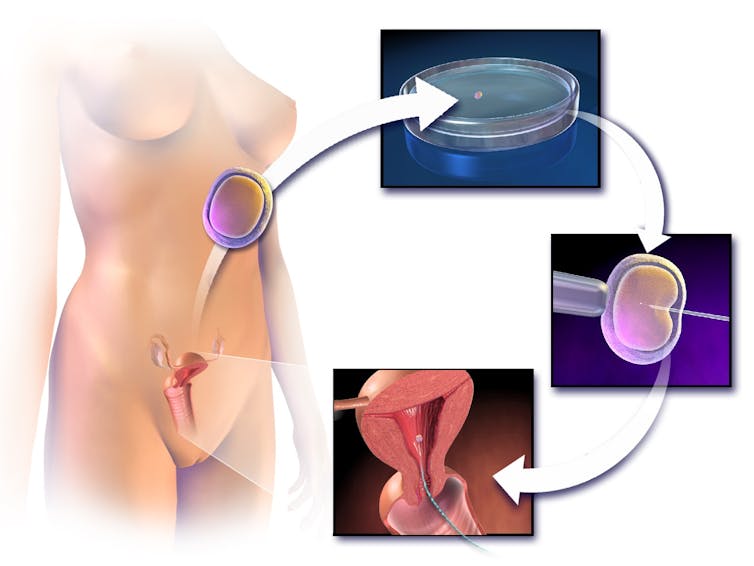

Now, 40 years after Louise Brown, the first child born to IVF (where the egg is fertilized with sperm in the lab instead of the body), this donation affects millions. The amazing breakthrough has gone beyond the seemingly insurmountable initial stages, and has evolved into areas such as the systematic freezing of ova and embryos for uncertain patients who are ready to continue their pregnancy. In addition, we as a society are now entering boundaries that include the experimental preservation of fertility for girls and prepubescent boys through the freezing of ovarian and testicular tissues. These methods, like those of Edwards and Steptoe 40 years ago, are promising for future generations

. However, this hope breeds fear and anxiety. Patients may fear that this is the last time they try, that it does not work, or that someone or something is wrong or interferes at the last minute. For society, many are wondering if new technologies are pushing us too far as we explore again and again, where people should go beyond our natural limits.

I am a reproductive endocrinologist at the UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital and the University of Pittsburgh. Here in our institution we are dedicated to finding innovative ways to preserve fertility. Our patients range from those who are about to undergo cancer treatments that could impair their reproductive potential to ambivalent transgender patients about their desire to conceive with their own sperm and eggs. They are facing this decision at a much earlier age than most of us would ever consider.

Science and the art of preserving fertility

My own research center has been improving access to care for these patients, and I am humbled by the methods that we have and in development. While we continue to fill the gap in experimental models, we seek to improve ovarian transplant methods in patients who are willing to attempt pregnancy with ovarian tissue previously preserved. At the Magee-Womens Research Institute, scientists and clinicians are working tirelessly to improve access to ovarian transplantation and develop ways for boys and men with frozen testicular tissues to survive. reach their reproductive potential. The world of reproduction is an exciting and growing field.

Blausen.com staff (2014). Medical Blausen Medical Gallery 2014., CC BY-SA

The preservation of fertility is a powerful example of how hope should not be blind. Although made widely accessible by IVF technology, research on fertility preservation began as early as the 1600s, when Dr. Harry Brown placed a jar of vinegar outside his window and thawed it on the floor. next day to discover that they were still alive. In the 1940s, researchers discovered that compounds called cryoprotectants could be used to freeze spermatozoa. In the 1950s, the first baby was born after conception with frozen sperm.

The breeding field then exploded. Babies were born after the conception of sperm extraction from the human body and births after conception of frozen embryos and frozen eggs were reported in the 1980s shortly after Louise Brown. Now men and women had options to preserve their fertility. The experimental label was removed from freezing in 2013 and now women are asking, "Should I freeze my eggs?"

For many couples, just knowing their options for family planning makes all the difference

By Chinnapong / shutterstock.com, CC BY-SA

The answer is deeply personal. Although not being more experimental, egg freezing is not currently indicated for elective use. While some insurance companies or employers may cover the significant costs badociated with the process, the likelihood is much less than that, for example, of in vitro fertilization for infertility. That said, the decline in age-related fertility is a real phenomenon and the number of women in the United States delaying the age of first birth continues to increase. Since women are born with all the eggs that they will ever have, the decline in age-related fertility is a steady process that accelerates in their thirties. What should you do?

For those who have a medical condition that will cause a high probability of fertility loss, the answer is not simple either. Although males can produce a specimen, the urgency of this person's chemotherapy may still dictate the number of attempts. Even without this emergency, males facing reproductive toxic therapy will still have to ask, "How often should I try to freeze sperm before I start chemotherapy?" For women, the question includes the need to delay medical treatment, p. chemotherapy or surgery, about two weeks for hormone treatment and the possibility that the treatment itself may result in risk.

None of these decisions is easy, but all still give hope and choice. For some, it's all that is needed. The women I see at the Magee-Womens Hospital often choose not to keep any eggs or embryos, but most are happy to be able to discuss the option. Males can freeze multiple samples, but then reject them when post-therapeutic badysis shows no effect on their sperm parameters. The preservation of fertility through these methods, and the hope that they bring, are now a common and accepted practice.

Preserving the fertility of sick children

Christian Lee K. / AP Photo

having challenges in front of us. Experimental options, such as ovarian tissue or testicular tissue preservation, are performed in academic centers such as the Magee-Womens Hospital for those who can not use conventional technology. These are almost exclusively for patients with a medical reason to suspect their future fertility is at risk. Pre-pubertal males who may be faced with a loss of future reproductive function as a result of planned chemotherapy may seek freezing of testicular tissues as their only option.

For a 10-year-old child with lymphoma, the decision to freeze tissues for the possibility of future children is almost inconceivable. Although no birth has resulted from testicular cryopreservation, current research by pioneers such as Dr. Kyle Orwig at the Magee-Womens Research Institute focus on several potential methods ranging from transplantation to the use of stem cells to restore the patient's fertility.

For women who can not go through the hormonal process to stimulate the production of eggs to freeze, freezing of ovarian tissue is possible. Although cryopreservation of ovarian tissue is still experimental, the first live birth of an ovarian tissue transplant was reported in 2004. Once we have seen enough healthy children born after this procedure, the experimental label will probably be removed.

However, when women suffer from ovarian cancer or other cancer spreads to the ovaries, there is concern that transplanting frozen tissue may resuscitate malignancy in the patient. Women with ovarian cancers are often not candidates for the transplant. These patients are still waiting and hoping that the preservation of fertility will overcome this next hurdle.

Four decades after the birth of Louise Brown by IVF, we have the opportunity to focus again on hope. Although the genetic manipulation of embryos has recently been brought to light, using CRISPR and the ethical fears and concerns, we should give equal attention to the work of researchers who are currently striving to preserve fertility for those who might otherwise miss this option. My research is focused primarily on access to care and the approaches that work best for patients with less traditional reasons for seeking fertility preservation, eg. transgender patients. We have found that a multidisciplinary approach that is gaining momentum to absorb the phenomenal amount of information we provide to patients works best for both short and long term care.

As a society, we have generally accepted that this important work is advancing in a positive direction. A gift that keeps giving, Edwards and Steptoe's research has set the bar high to persevere in order to develop options for patients who might otherwise lack of choice.

Source link