[ad_1]

It seems that researchers in China have facilitated the birth of the first "baby designer" – in fact, babies, binoculars supposed to be genetically resistant to HIV. The scientist who created the embryos, as well as American scientists such as George Church of Harvard, praised the beneficent intention of producing a child resistant to the disease. Who could argue with such good intentions?

But, once you can do it with a gene, you can do it with any gene – like those related to the level of education. Those who praise Chinese research have not given any mechanism, rules, or regulations that would allow the editing of human genes for purely beneficial purposes. As the old proverb says, "hell is paved with good intentions".

For more than 20 years, I focused my research on debates about the editing of human genes and other biotechnologies. I have seen these debates unfold, but I am shocked by the speed of developments.

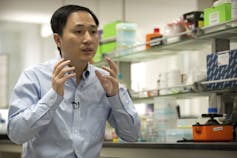

Chinese scientist He Jiankui claimed to have modified the embryos of seven couples during a fertility treatment in China. His goal was to disable a gene that encodes a gateway protein that allows the HIV virus to enter a cell. One woman fed two of these embryos and this month gave birth to non-identical twins that, according to Jiankui, would be resistant to HIV.

Photo AP / Mark Schiefelbein

Given the secrecy badociated with it, it is difficult to verify Jiankui's claim. The research was not published in a peer-reviewed journal, the parents of the twins refused to talk to the media and no one tested the girls' DNA to check what Jiankui had said. But what is more important at the moment is that scientists are trying to create these improved humans that could pbad this trait to their offspring.

Eugenics Mainline and Reform

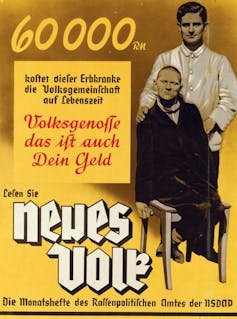

The creation of an "improved" human species has long been the dream of eugenicists. The main old-school version of eugenics supposed that superior traits were found in particular races, ethnicities and, in particular, in the United Kingdom, social clbades. This logic culminated in the Holocaust, where the Nazis concluded that some ethnic groups are genetically superior to others and that the "lower" groups should be exterminated and completely erased.

Author unknown / Wikimedia Commons

The revelation of the Holocaust destroyed the main eugenics, but a "reformist" eugenics appeared in the fifties. This mark of eugenics meant that "superior traits" could be found among all ethnic groups. All that was to happen was to ensure that these superior people produced more children and discouraged those with inferior traits from reproducing. It turned out to be difficult.

But in the early 1950s, Francis Crick and James Watson discovered the chemical structure of DNA, suggesting that human genes could be enhanced by chemical modification of their reproductive cells. The eminent biologist Robert Sinsheimer wrote in 1969 that the new genetic technologies of the time allowed "a new eugenics". According to Sinsheimer, the old eugenics required the selection of individuals to reproduce and eliminate the unfit. "The new eugenics would in principle allow for the conversion of all unfit into higher genetic levels … because we should have the potential to create new genes and new qualities that are unthinkable."

The slippery slope of the debate on gene editing

The modern ethical debate on the editing of human genes goes back to that time. The debate was implicitly organized as a slippery slope.

At the top of the slope was an unquestionably virtuous act of gene editing – a step that most people were willing to take – such as sickle cell repair. However, the slope was slippery. It is very difficult to say that changing other traits that are not fatal, such as deafness, are not equally acceptable. Once you understand how to change a gene, you can change any gene, regardless of its function. If we correct sickle cell disease, why not deafness, late heart disease, lack of "normal" intelligence or, at the bottom approach, a lack of superior intelligence?

AP Photo / Eraldo Peres

At the bottom of the slope was the dystopian world where nobody wants to finish. This is generally described as a society based on the total genetic control of offspring, where people's lives and opportunities are determined by their genetic genealogy. Today, the bottom of the slope is represented by the film "Gattaca" of the late 1990s.

Walking on the slope

In the 1970s, virtually all participants in the debate showed up on the slope and approved somatic gene therapy – a strategy for the cure of genetic diseases in the bodies of living people where genetic modifications would not be pbaded on to any offspring. The participants in the ethical debate on gene editing crossed this slope because they were confident that they had blocked any possibility of slippage by creating a strong norm against the modification of the DNA pbaded on to the next generation: the germ wall . (The germline means to influence not only the modified person, but their descendants.)

Somatic changes could be debated, but researchers would not break the wall to change people's legacy – to change the human race as eugenicists have long wanted. Another hurdle to the road to hell that has proven permeable was the wall that separated the blockage of an illness and the improvement of an individual. Scientists could try to use gene editing to avoid genetic diseases, such as sickle cell disease, but not to create "improved" humans.

The recent actions of the Chinese scientist cross both the boundaries of the germ line and the improvement. This is the first known act of editing human germ line gene. These twins can pbad on their new resistance to HIV to their own children. It is not intended to prevent a genetic disease such as sickle cell disease, but to create an improved human being, although it is an improvement made in the name of the fight against infectious diseases.

Call for a new wall

Unlike previous years of the debate on the editing of human genes, no argument is given to us to know where these applications would stop. Those who advocate the use of gene editing by Chinese scientists do not suggest a wall further down the slope that can be used to ensure that, in allowing this supposedly beneficial application, we will not finish at the end of the account. Many scientists seem to think that a wall can be built with "disease" applications in the acceptable part of the slope and "highlighting" in the unacceptable part below.

However, the definition of "disease" is notoriously fluid, with pharmaceutical companies frequently creating new diseases to be treated in a process that sociologists call medicalization. Moreover, is deafness a disease? Many deaf people do not think so. Nor can we rely on the medical profession to define the disease, as some practitioners engage in better-performing activities (eg Plastic Surgery). A recent report from the National Academy of Sciences concluded that the distinction between illness and improvement is hopelessly confused.

Thus, although the scientists defending the first improved baby may be right, it is a moral good. Unlike previous commentators, they have given society no wall or barrier to walk with confidence on this new slippery slope. This is to avoid the responsibility of saying that "society will decide what to do next," as He Jiankui did, or to say that research is "justifiable", without setting a limit, as did George Church from Harvard University.

For a responsible debate, participants must state not only their conclusion about this act of improvement, but also indicate where they will build a wall and, critically, how that wall will be maintained in the future.

Source link