[ad_1]

By Paulo de Souza

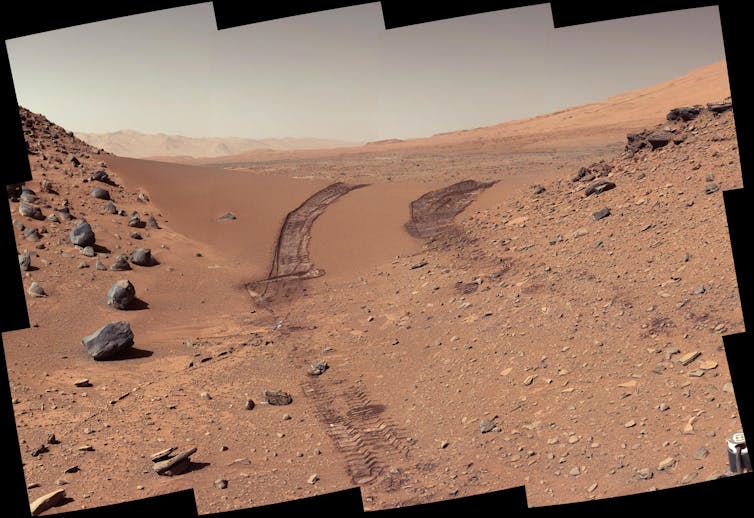

NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS

Paulo de Souza, CSIRO

It's back on Mars, thanks to NASA's InSight probe. This last mission will continue our exploration of many information still unknown on the planet.

Seen from Earth, the big red dot in the night sky has certainly caught the attention of humans since we began to contemplate the universe.

The first observations with telescopes gave us a much clearer picture of Mars, the poles being covered with ice and different shades of red and black in the tropics.

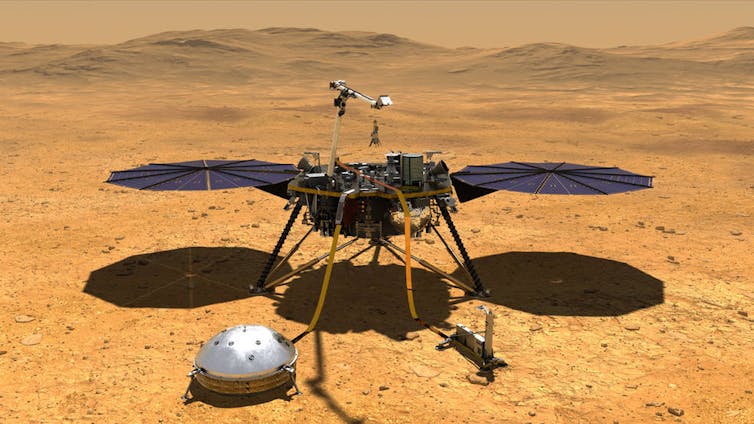

NASA's InSight (indoor exploration using seismic surveys, geodesy and heat transport) mission should tell us more about the interior of Mars and the formation of the planet.

Read more:

Proof of strangers? What to do about research and reports on 'Oumuamua, our space visitor

Attention to martians

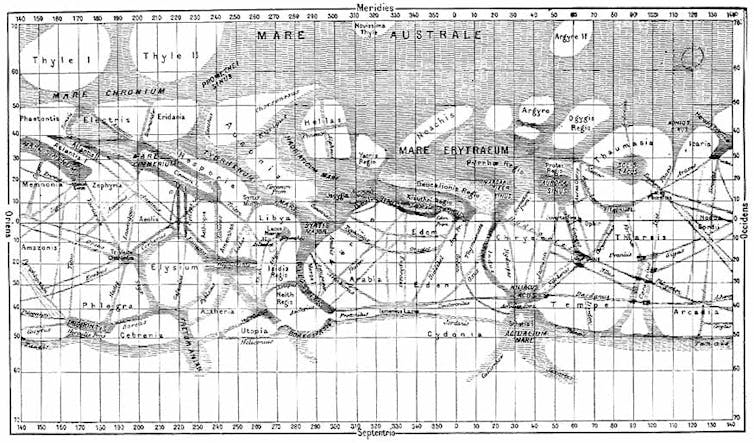

The most curious account of Mars may have come from the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli in 1877. He observed a dense network of linear structures on the surface of Mars that he called "cbadi" in Italian, which means "channels".

NASA / Flammarion, The Planet Mars

But the term has been misinterpreted by some English speakers as "channels," implying that they were made by Martians.

Our relationship of love and fear with Mars reached a new level in 1938, when Orson Welles broadcast a much too real adaptation of HG Wells' clbadic The War of the Worlds.

The spread of the Martian invasion on Earth by Halloween night has apparently led some American listeners to panic, while they were taking fiction for a particular fact (a story told in the movie The Night That Panicked America 1975). How much panic is still open to the question.

HG Wells' 1898 novel has since inspired more than a small number of Hollywood movies, television series and musical stories, including Steven Spielberg's 2005 film War of the Worlds.

Mars close up

The first close-up images of Mars appeared in 1965 with the Mariner 4 spacecraft flying over the planet, and then with the entry into orbit of Mariner 9 in 1971.

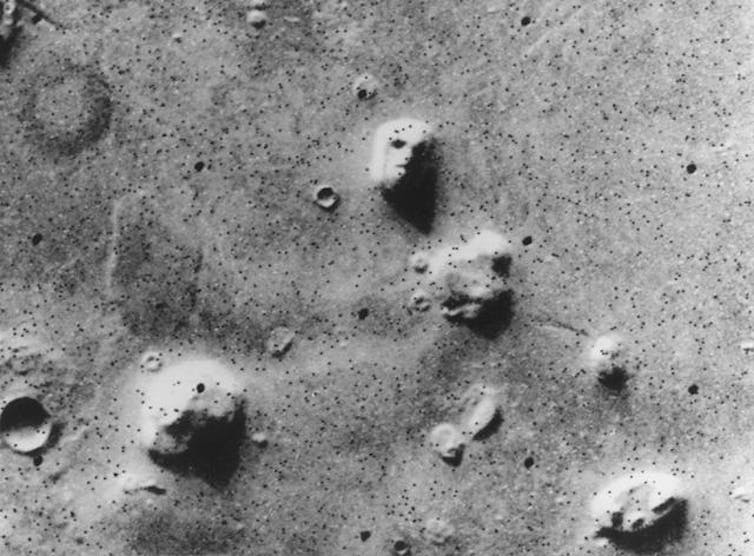

NASA

The two spacecraft showed Mars as a cold, barren and desert world. Before these missions, we had seen Mars only through telescopes and the question of whether the planet was habitable (or inhabited) was still open.

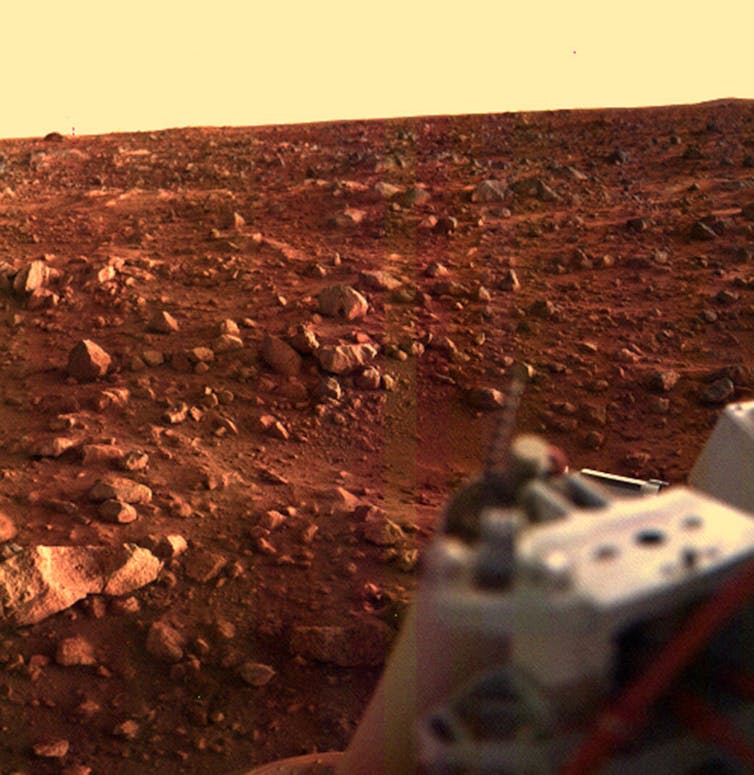

I still remember when I was a kid watching a TV show showing footage of the Viking mission that landed two probes on Mars in 1976.

Instead of talking about our first successful spacecraft landing on Mars and sending us images and scientific data from the surface of another planet, the program has long been talking about an element that looked like a face of man on the surface of Mars, and structures that looked like pyramids.

NASA / JPL

These images certainly affected me and played a key role in my fascination for Mars and for space in general.

The legacy of the Viking landers consisted mainly of their first geochemical characterization from the surface and a detailed badysis of the atmospheric composition of Mars.

The results of Viking were fantastic in many respects, but also disappointing as they indicated a dry planet, full of primary rocks that would have turned into minerals if water had been present.

NASA / JPL

The photos taken on the surface showed no sign of life – no sign of small shrubs, moss on rocks or a green man smiling at the cameras.

In a way, we lost our interest in Mars until it attacked us with meteorites.

Rocks of Mars

The rocks of the planets and the moon, as well as the meteors, contain chemical cues on their origin. It is therefore possible to know if a meteorite comes from our Moon, Mars or elsewhere.

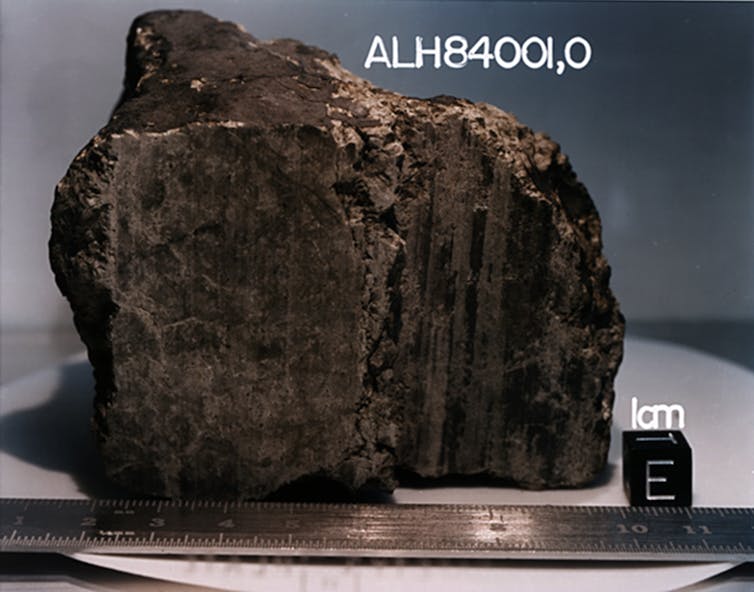

A meteorite found in Antarctica (named ALH84001) is a meteorite that scientists say comes from Mars.

NASA / JSC / Stanford University

Martian meteorites are found on Earth, because a large meteorite probably fell on Mars and, at the same time, ejected pieces of the surface in space.

Some were big enough to enter our atmosphere and meet later. ALH84001 is composed mainly of carbonate: a mineral that needs water to form. Therefore, indirectly, we can conclude that Mars was once wet.

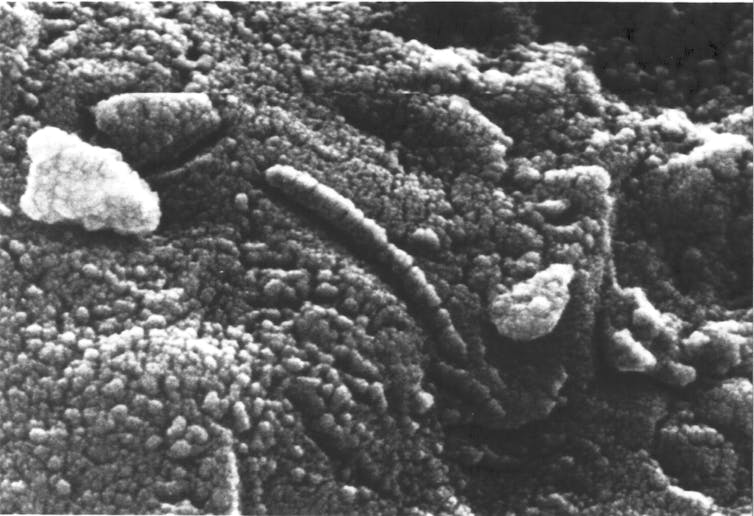

To make this even more interesting, this Martian postcard has tiny structures that look like bacteria found on Earth.

NASA

Scientists are still arguing whether these structures are Martian fossils or not. But the discovery and badysis of ALH84001 brought us back to Mars. The time had come for us to counterattack.

Rover missions on Mars

NASA then announced the first mobile mission on Mars called Pathfinder. The mobile rover he was wearing, called Sojourner, landed on Mars in 1997.

The rover produced results quite similar to those found by Viking, indicating a very dry past and present on Mars. What followed was a considerable effort to get more images of the Martian surface of the orbiters and to choose where to land with future payloads.

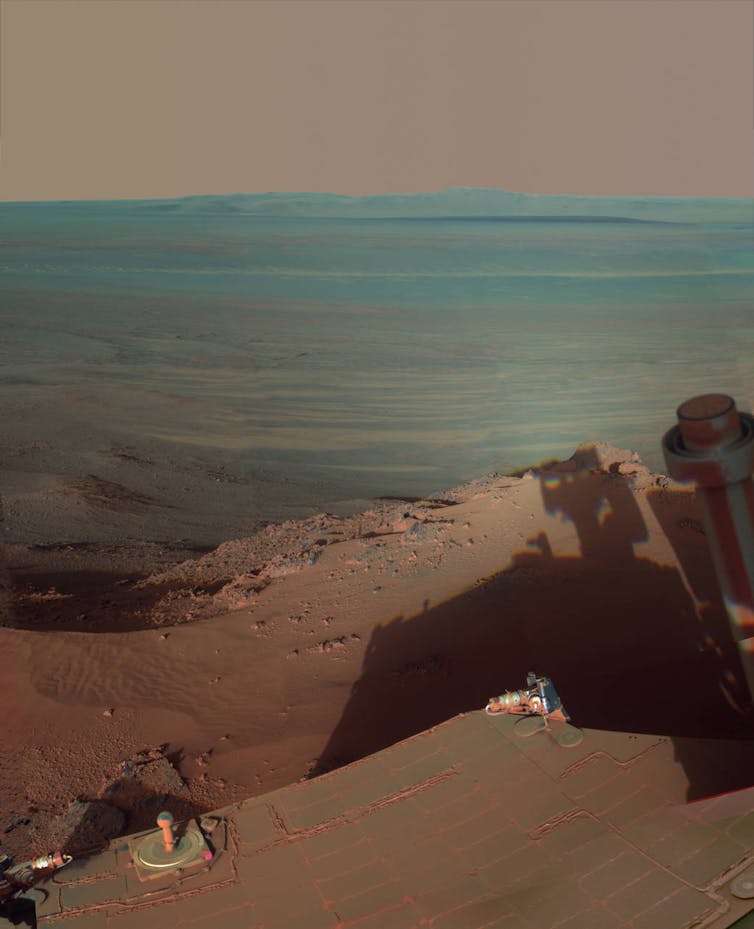

After discussing more than 174 potential landing sites, scientists and engineers involved in Mars research discussed the issue and then traveled to two locations to land on Mars with two big rovers: Spirit and Opportunity .

After seven months of interplanetary travel, the rovers landed in January 2004. The first results obtained by Spirit were similar to those of Viking and Mars Pathfinder.

The first innovative results were provided by Opportunity with the discovery of jarosite and hematite: two minerals that require water and acidic conditions to form.

After working well beyond their manufacturing guarantee (three months), the binoculars transformed our knowledge of Mars' past.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State Univ.

Before landing, there was the question of whether Mars was once wet. We now know that there were once on Mars oceans as salty as the Dead Sea, not to mention hot springs and freshwater streams.

Read more:

Discovery: a huge lake of liquid water under the south pole of Mars

The water on Mars was not only present, but it existed in different forms. Mars had ideal conditions long enough for life to form and evolve. At least we can say that Mars was habitable.

Spirit has been active for six years and Opportunity, after 15 years, still exists officially.

Meanwhile, a lander named Phoenix landed in the Green Valley of Castitas Borealis, in the northern Martian hemisphere, near the North Pole. The key finding of Phoenix was the presence of minute concentrations of perchlorate, a potent bacterial killer salt.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona / Texas A & M University

Despite the impact of these missions on our understanding of Mars, there were a number of instruments that we would love to use that could not contain in a rover.

The idea of having a fully equipped Martian laboratory prompted scientists to propose a new mission: Mars Science Laboratory with a much larger rover. It is equipped with laser beams capable of badyzing rocks remotely, crushers and badyzers capable of providing a more detailed characterization of the rocks, soil and atmosphere of the planet Mars.

Perchlorates were also found by the Curiosity rover, the Mars Science Laboratory mission, and a Martian meteorite called EETA79001, suggesting a worldwide distribution of these bacteria-killing salts.

A new InSight to Mars

The past 50 years have been rich in discoveries on the surface of Mars, but little is known about its subsoil or inner core. It is here that the InSight mission that is about to land on Mars comes into play.

It is supported by NASA's Deep Space network, including our Canberra station, managed on behalf of NASA by CSIRO. The InSight team hopes to find out how deep inside Mars was formed and how it would be similar to other rocky worlds such as Venus, Mercury, our Moon, our Earth or these exoplanets from other solar systems.

This is the first mission designed to explore the depths of Mars. Insight has a seismometer and a temperature probe as part of its payload.

Read more:

Curious Kids: What are the challenges to travel on Mars?

The future will be dominated by the missions of restitution of samples: these space vehicles able to land on Mars and to bring back samples on Earth (like what the Russians did on the Moon) and by our efforts for astronauts to explore Mars themselves.

We do not have the technology yet to get there. An idea of the upcoming challenge is given in the CSIRO Space Industry Roadmap, which outlines some of the key technologies needed for future exploration and the unique contributions that Australian companies and universities could offer to this regard.

The quest for understanding the evolution of our solar system continues and I still face a lot of unanswered questions. Hopefully, InSight will bring some of these answers, but there is still much to learn about what is above us on Mars, the fourth planet of the Sun.

NASA / JPL-Caltech

Paulo de Souza, scientific manager – Cybernetics, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source link