[ad_1]

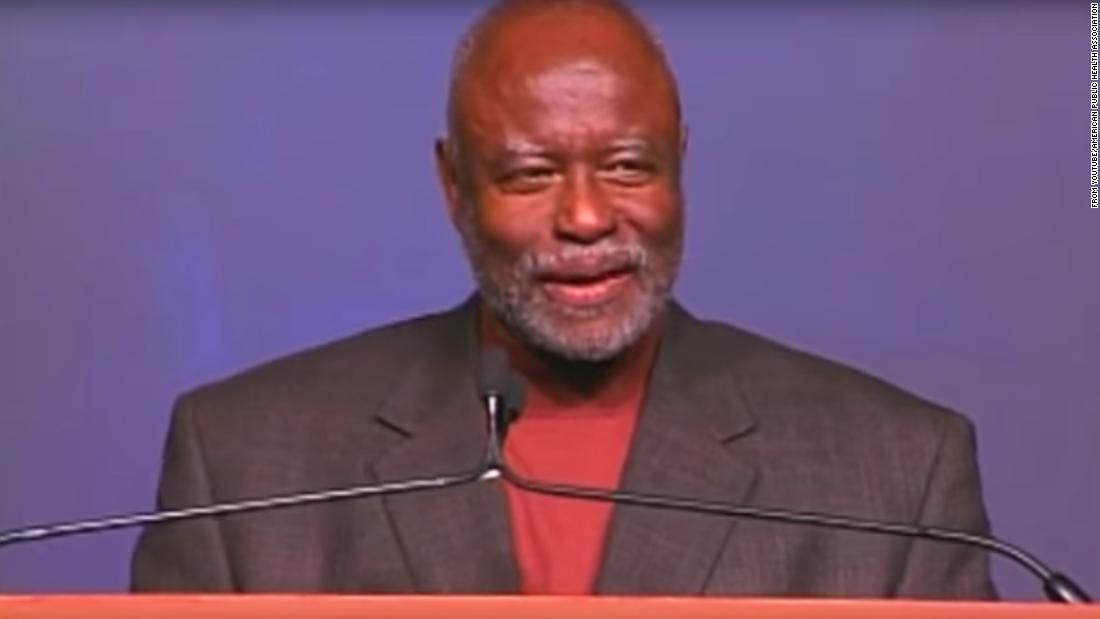

Jenkins, an epidemiologist, played an important role in exposing this experience to the general public. He shocked his outrage at the racism behind the Tuskegee study and has always striven to reduce racial disparities and discrimination in health care.

Jenkins noted that the infamous study was actually the result of an effort begun with good intentions, to try to solve the problem of syphilis in the early twentieth century in America.

The study offered free medical examinations, meals and burial insurance to recruit 600 black men, 201 of whom did not have the disease.

Jenkins recalled that initially, the study was supposed to track untreated men only for one year. But in 1936, it was decided to follow them until death. Men were not informed of what was being investigated and those who were carriers of the disease were not treated for the treatment of syphilis – even when penicillin had become an effective treatment in 1947. Many men ended up infecting their syphilis wife, to their children.

Jenkins, who began his career in 1967 as one of the first African-Americans to join the corps at the command of the Public Health Service, learned he had been informed of the study. in 1968 and had worked with his fellow epidemiologist, Peter Bauxum, to attract arrest.

"These efforts have been postponed until Peter ends up with the Associated Press reporter who was able to write this first article (about the study)," he said. declared.

The study only came to an end in 1972, after congressional hearings and the appointment of an advisory group to review it. She determined that the knowledge gained was "rare" in relation to the risk to the subjects.

A class action suit followed quickly, resulting in settlement and compensation of $ 10 million for living participants, their spouses and children, such as medical benefits and funeral services.

The last participant in the study died in 2004, and the last widow receiving benefits died in 2009, according to the CDC. In 2015, 12 children of the study participants were receiving medical and health benefits.

He was a vocal critic of racism in health care

Jenkins then helped to take care of the many men who took part in the study by assuming the role of participant health benefits program manager, who offered them medical services.

He remained a strong advocate for reducing racial disparities in health. He has often criticized the medical community for what he saw as his reluctance to take an interest in the American racist heritage and its role in the chronic health problems that affect minorities.

"This is the only health problem for which we want to study racism, a racial symptom rather than the ideological factor," he said in his speech. "It's unbelievable for me as an epidemiologist.To resolve disparities in health, we also need to study racism."

A Quaker service for Jenkins is scheduled for March 23 in Decatur, Georgia. A memorial service will be held on April 6 at Morehouse College.

[ad_2]

Source link