[ad_1]

Deadly police shootings did not appear to subside, even amid the coronavirus pandemic, and blacks, Latinos and Native Americans continue to be disproportionately affected by deadly police shootings compared to whites , according to a study released Wednesday by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Such shootings are “so common that even during a national pandemic, with far fewer people traveling outside their homes and police departments reducing contact with the public so as not to spread the virus, police continued. to fatally shoot people at the same rate. far into 2020 as they did in the same period from 2015 to 2019, ”according to the report, which was based on analysis of data from the University of Nebraska at Omaha .

The data also showed that several states experienced an increase in the rate of police shootings in 2020 over the previous five years.

“We thought the police might slow down the killing of people during the pandemic,” said Udi Ofer, director of the ACLU’s Justice Division. “We were wrong.”

From January to June of this year, there were 511 fatal shootings by police, according to the report, up from 484 during the same period in 2019. In the first six months of 2018, there were 550 fatal shootings. by the police; in 2017, there were 493; in 2016, there were 498; and in 2015, there were 465.

Researchers examined figures from a database maintained by the Washington Post, which tracked the deadly police shootings through press accounts, social media posts, and police reports following the murder. in 2014 of black teenager Michael Brown by police in Ferguson, Missouri. The database found that fatal police shootings remain at a constant of nearly 1,000 per year since 2015, which the Post said can be explained by a “theory of probability” which suggests that “the amount of ‘Rare events in huge populations tend to remain stable in the absence of major societal changes, such as a fundamental shift in policing culture or extreme restrictions on gun ownership. “

The researchers said they wondered if a once-in-a-century public health crisis that resulted in increased social isolation would lead to a reduction in police killings.

“We want to voice the alarm that even when the country was on lockdown at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic … that did not stop police from shooting people fatally at the same rate,” Ofer said. The report does not ask why the number of shootings remained at the same level in 2020, although Ofer added that he highlights how the police have continued in those months and pointed out that not everyone was unable to quarantine his home.

The report only looked at fatal shootings in service and not other types of incidents in which people died during or after an encounter with police.

After the United States began reporting coronavirus deaths in early March, the number of fatal shootings per week has not declined from the first two months of the year. But researchers noted that within five weeks of George Floyd’s May 25 murder, a black man who died after a Minneapolis police officer stabbed his knee into Floyd’s neck, fatal gunfire from the police “fell precipitously” from over 25 a week to under 15.

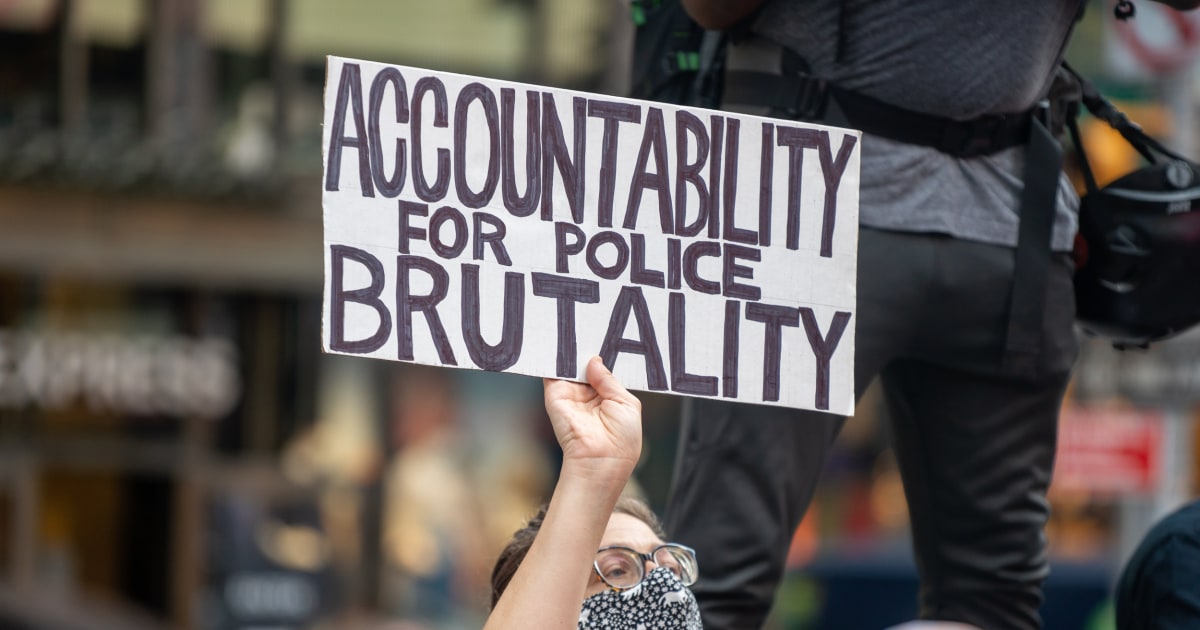

Floyd’s death has led to a wave of global protests against police brutality, as well as calls from activists for police reform and even the dismantling or dismantling of police services. Some states and departments, including Minneapolis and New York, have announced significant changes in policing.

Despite a notable drop in fatal police shootings in June, the ACLU report says it “cannot draw meaningful conclusions from data over such a short period” and that the numbers must continue to be tracked to “better understand whether, in fact, the protests, public outrage and accompanying policy changes have reduced police shootings.”

The ACLU report also identified seven states – Alabama, Alaska, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Montana and Nevada – as having experienced significantly more fatal shootings in the first six months of 2020 compared to previous years.

Emily Greytak, director of research for the ACLU, said more analysis was needed to determine why. Historically, she said, there has been a lack of comprehensive national data on police shootings and analysis of how racial bias plays out in deadly encounters with police.

While fatal police shootings have remained relatively unchanged in the first six months of 2020, general crime has fallen in major US cities compared to previous years.

This drop can presumably be attributed to people staying indoors during the pandemic, said Christopher Herrmann, former supervisor of criminal analysts at the New York Police Department and professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

This summer saw an upsurge in violent crime, including shootings and murders, in cities like Atlanta, Chicago, New York and Philadelphia. Herrmann said the typical increase in summer crime as well as the effects of the pandemic, including job losses, are suspected factors.

The Council on Criminal Justice, a non-partisan think tank, studied crime data from 27 cities from January 2017 to June 2020 and found that rates of homicide, aggravated assault and assault with a weapon fire had started to “increase significantly by the end of May. Several factors likely explain these trends, including diminished police legitimacy as a result of Floyd’s murder.”

“Of course all of these things are going to make police more careful, less proactive, less productive,” Herrmann said, adding that officer morale and a “COVID effect” in which police are more distracted due to concerns over viruses are related.

Across the country, discussions over the allocation of police funds have flared up in cities like New York, where city council voted in June to cut $ 1 billion from the budget of the largest police department. across the country, and Houston, where city council that same month rejected a proposal to move nearly $ 12 million from the police budget to fund large-scale police reform initiatives also favored by advocates of the community, who prefer that more money be spent on improving social and public health services.

After welcoming a new class of 74 recruits to the police academy this week, Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo said other members of the community have made it clear they don’t want less. policing, “they wanted good policing.”

Some cities “are making cuts without a real study of the consequences,” said Acevedo, who is also this year’s president of the Association of Chiefs of Large Cities, which represents about 69 urban police departments.

The ACLU supports the reduction of law enforcement roles and responsibilities to reduce the number of fatal encounters. The group says the government should pull back from police budgets and instead redirect money to social services and community programs that can help with mental illness and other issues, and end police interactions for ” non-serious offenses ”, including minor roadside checks.

After Floyd’s death, Steven Casstevens, president of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, a non-profit organization representing law enforcement officials, said that in recent years agencies have been working to reduce the use of to force and maintain police accountability.

Casstevens, the Buffalo Grove, Ill., Police chief, urged all agencies to participate in the FBI’s National Use of Force Database, which has been criticized for being incomplete and ineffective in guiding police reform, and officers to adhere to a use of force. policy that places a value on the preservation of human life.

But simply unblocking or transferring law enforcement resources is not the solution, Casstevens added.

“Change will require both dedicated resources and a sustained commitment from police chiefs, community members and elected officials,” he wrote in an open letter. “Now is not the time to further limit the capacity of police services.”

In Houston, where the homicide rate is up 27% from a year ago, Acevedo said the pandemic, along with the rise in domestic violence, drug and mental health issues were fueling all the bigger problem. Earlier this month, the city experienced its 18th shootout involving police in 2020.

While Acevedo has won praise for marching with activists after Floyd’s murder, he has also resisted criticism from some protesters calling for more transparency in Houston.

He said on Tuesday that his department had been able to halve the number of shootings involving officers over the past eight years, and that there was a need to examine why each individual case had ended in death.

“Police detractors only want to focus on numbers and race, but they don’t want to look at individual circumstances,” he said. “Look at the facts, look at the evidence, then decide whether prosecutors or the criminal justice system didn’t hold the officers accountable. Don’t use a broad approach.”

He added that the proliferation of officer corps cameras and the release of public capture video of police encounters are forcing departments to improve their training.

“We’ve come a long way, but the work never stops,” Acevedo said.

ACLU researchers argue that while violent crime is trending on the rise, this still shouldn’t open the door to an increase in deadly clashes with police.

“Whether crime is up or down, whether we are in a pandemic or not, the police keep killing people,” Ofer said.

CORRECTION (August 19, 2020, 2:55 p.m. ET): An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the police shootings in Houston this year. There have been 18 shootings involving officers, but not all of them have been fatal.

[ad_2]

Source link