[ad_1]

Most people wonder when and how the COVID pandemic will end and there are still no easy answers.

The word “endemic” is mentioned regularly, especially among leaders and public health experts when discussing potential future scenarios. So it’s important to define exactly what would mean COVID is rampant.

Scientists predict that COVID will become endemic over time, but there will always be sporadic outbreaks where it gets out of hand. The transition from pandemic to endemic will likely play out differently in different places around the world.

Read more: Israel was a leader in the COVID vaccination race – so why are cases increasing there?

“Outbreak”, “Epidemic”, “Pandemic” and “Endemic”

Let’s first recap the public health terms Australians have increasingly used in conversations over the past 18 months. These words cover the life cycle of the disease and include “epidemic”, “epidemic”, “pandemic” and “endemic”.

An outbreak is an increase in cases of illness over what is normally expected in a small, specific location, usually over a short period of time. Foodborne illnesses caused by contamination with Salmonella are common examples.

Epidemics are essentially epidemics without strict geographic restrictions. The Ebola virus that spread to three West African countries between 2014 and 2016 was an epidemic.

A pandemic is an epidemic that spreads in many countries and on many continents around the world. Examples include those caused by influenza A (H1N1) or “Spanish flu” in 1918, HIV / AIDS, SARS-CoV-1, and the Zika virus.

Finally, the normal circulation of a virus in a determined place over time describes an endemic virus. The word “endemic” comes from the Greek endemic, which means “in population”. An endemic virus is relatively constant in a population with largely predictable patterns.

Viruses can circulate endemically in specific geographic regions or around the world. Ross River virus circulates endemically in Australia and Pacific island countries, but is not found in other parts of the world. Meanwhile, the rhinoviruses that cause the common cold are circulating endemically around the world. And influenza is an endemic virus that we monitor for its epidemic and pandemic potential.

Read more: Whitewash in the age of COVID: Australian health services still leave vulnerable communities behind

What does the usual path from pandemic to endemic look like?

Over time and through public health efforts, from mask wear to immunization, the pandemic could go away like smallpox and polio – or it could gradually become endemic.

Host, environmental and virus factors combine to explain why some viruses are endemic while others are epidemic.

When we look at the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID, we see that it infects human hosts without prior immunity.

In terms of the environment, the virus is best transmitted in cold, dry, overcrowded, nearby, confined and poorly ventilated places.

Each virus has its own characteristics, from the speed of virus replication to drug resistance. New strains of COVID spread faster and cause different symptoms.

Viruses are more likely to become endemic if they adapt to a local environment and / or have a continuous supply of susceptible hosts. For COVID, these would be hosts with little or no immunity.

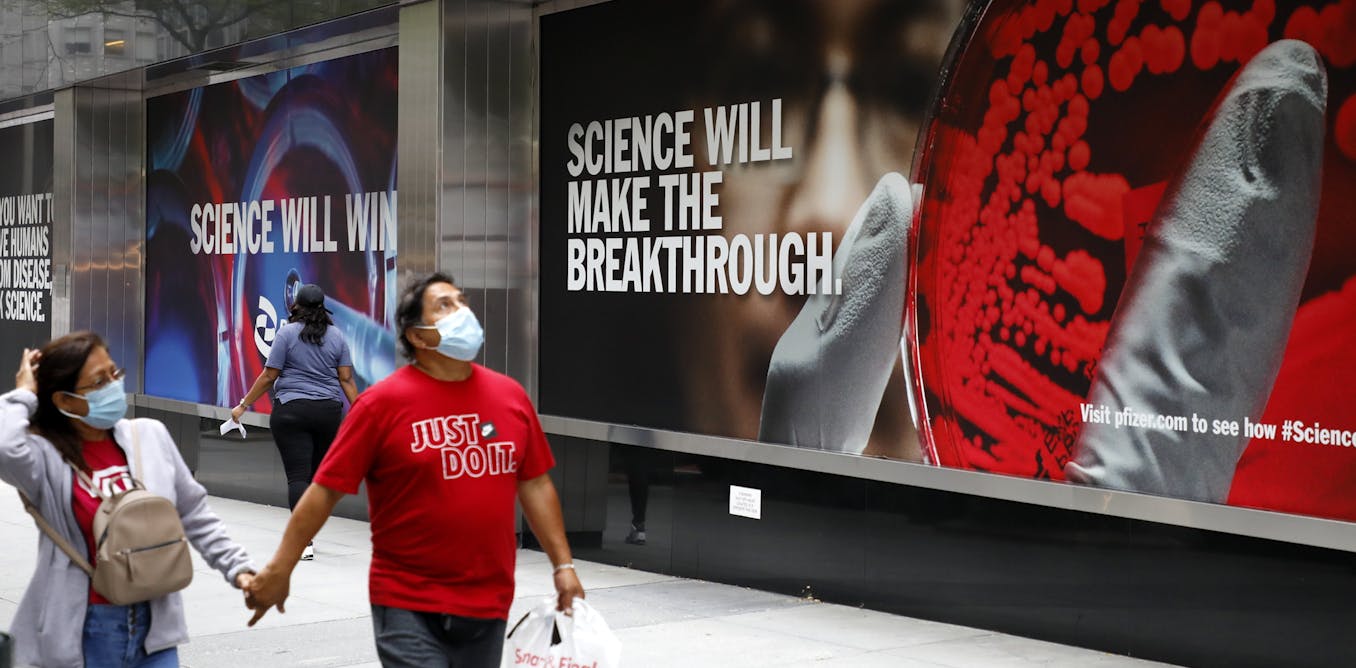

AAP / Dan Himbrechts

Read more: Four factors that increase the risk of vaccinated people contracting COVID

How long will it take for COVID-19 to become an endemic disease?

Scientific mathematical modeling gives an idea of the likely outcomes of the COVID epidemic.

Most public health experts currently agree that COVID is here to stay rather than going away like smallpox, at least for a while. They expect the number of infections to become fairly constant over the years with possible seasonal trends and occasional smaller outbreaks.

Globally, the road from pandemic to endemic will be difficult. In Australia, our national and state leaders are announcing future plans to reopen businesses and possibly borders. This process will result in the second national outbreak of COVID. People will die and our health systems will be challenged. Vaccination rates will protect many, but there are still those who will not or cannot get vaccinated. Collective immunity (through vaccination or infection) will play a key role in ensuring that we move towards endemic COVID.

Over time, scientists predict that COVID will become more prevalent in unvaccinated youth or those without prior exposure to the virus. This is what happens with cold coronaviruses. Despite periodic spikes in the number of cases each season or immediately after economic, social and travel restrictions are eased, COVID will eventually become more manageable.

Katsumi Tanaka / AP / Yomiuri Shimbun

It won’t be the same everywhere

Countries will not enter an endemic phase at the same time due to varying factors related to host, environment and virus, including vaccination rates. The availability and deployment of booster vaccines each year or season will also shape this path. Poor vaccination coverage could allow the virus to maintain itself at an epidemic level for longer. In a place where immunity is rapidly waning and there are no boosters available, COVID could go from endemic to epidemic.

Once we see a stable level of SARS-CoV-2 transmission indicating a new “baseline” of COVID, we will know the pandemic is over and the virus is endemic. This will likely include minor seasonal trends as we are now seeing with the flu.

The most important thing we can do to help reach a safe level of endemic COVID is to get vaccinated and continue to adhere to safe practices for COVID. In doing so, we protect ourselves, those around us, and move forward together towards an endemic phase of the virus. If we don’t work together, things could get worse very quickly and prolong the end of the pandemic.

[ad_2]

Source link