[ad_1]

Sara Cherry has a visceral memory of the time when Asian tiger mosquitoes, Aedes albopictus found their way into the Philadelphia area

"I had been there. I used to eat out with my lab when I started working here at Penn, "she says." But then the tigers came and started to terrorize us and we had to eat at home. inside. They are aggressive and their stings cause scars. "

Vectors of viral diseases including yellow fever, Zika, dengue and chikungunya, A. albopictus and its close relative Aedes aegpyti have undergone a spectacular global expansion these recent years, and now live with satisfaction in courtyards and outdoor spaces frequented by hundreds of millions of Americans.

Cherry, a professor at Penn's Perelman School of Medicine, who studies mosquito-borne viruses, tigers are emblematic of changes in vector-borne diseases, changes often brought about by climate change and globalization.

According to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, mosquito-borne and tick-borne diseases represent a growing public health problem. From 2004 to 2016, the agency found that insect-borne diseases more than tripled, with nine new diseases in the United States. emerging diseases during this period. Meanwhile, in recent months, an introduced tick species has been reported in the eastern United States, raising concerns about how this new landscape actor could influence disease risks.

favored many of these diseases.

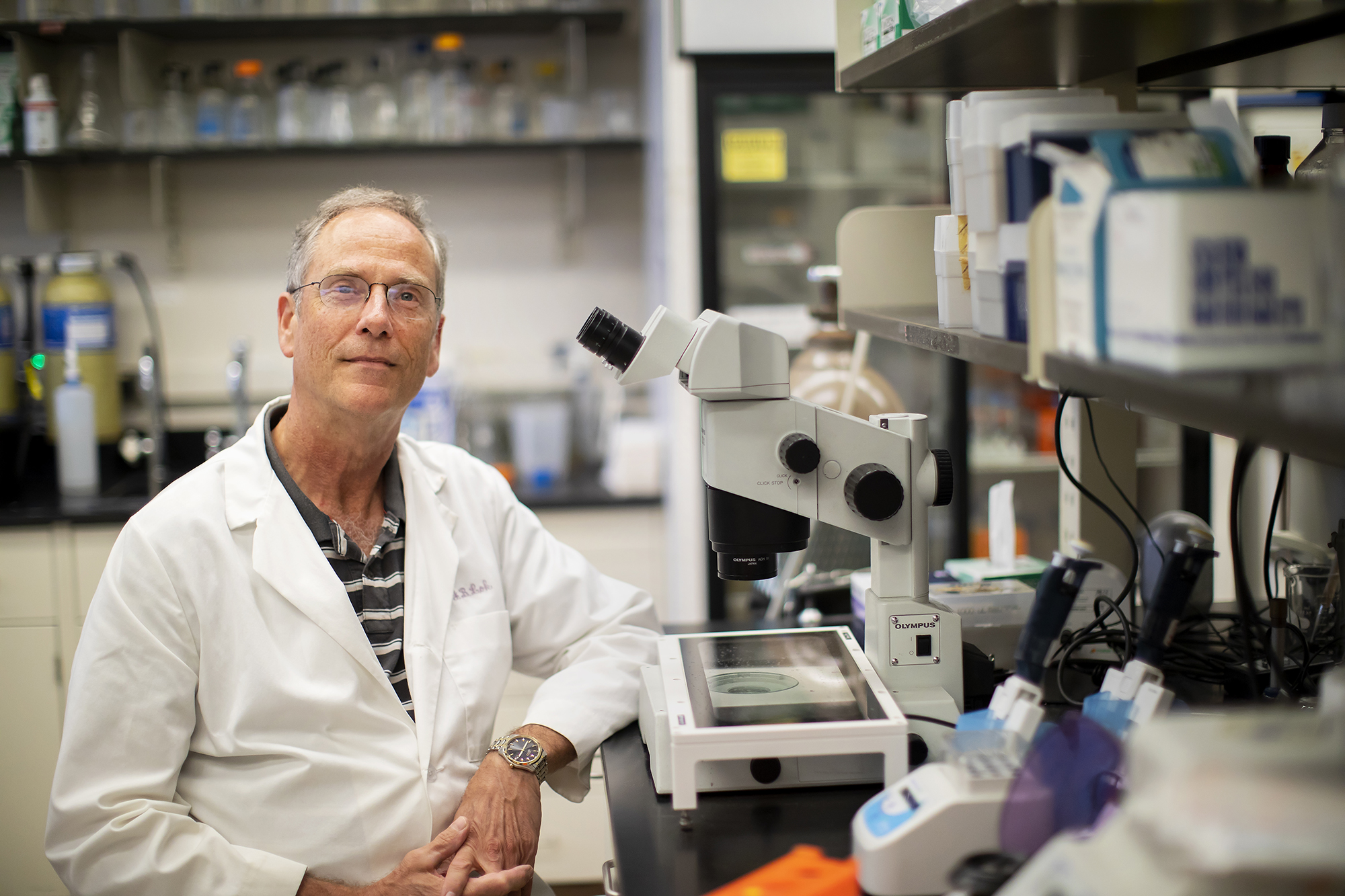

James Lok, professor of parasitology at the School of Veterinary Medicine.

With potential dangers lurking in the bodies of tiny insects, the question may surface: is it safer to venture out? Penn's researchers, following the news and progressing in the lab, offer a clear, albeit uncut, vision of the state of vector-borne diseases. The threats may be real, they note, but the precautions are usually simple.

Risks, old and new

James Lok of Penn's School of Veterinary Medicine specializes in parasitic biology, but also teaches students the ins and a wide variety of zoonotic diseases transmitted by insects. He sees a link between global travel and global trade and the new threats posed to the continental United States by exotic diseases formerly badociated with the tropics, such as the Zika virus and the chikungunya virus.

"The global economy and globalization have generally been social trends that have favored many of these diseases," says Lok. "There are a lot of ways that a tick like the exotic one found in New Jersey can hitchhike on cattle and get here, then when they're inside, they're in it."

The introduced tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis with a common long-horned or bush tick name, was found on a sheep last year and appears to have pbaded winter in New Jersey. This spring, reports were also released in Virginia, West Virginia and Arkansas.

"This tick is known to be an aggressive invader," says Dustin Brisson, a biologist at the School of Arts and Sciences. the evolutionary trends of the bacteria responsible for Lyme disease and Ixodes scapularis the blacklegged tick that carries it. H. longicornis is already known to spread viral diseases in his native East Asia.

Brisson says that with a new vector like this, researchers usually have two sets of questions. "The most immediate are related to its vector competence," he says. "Can he transmit diseases that we already have here in North America?" Where are the risks? "

Equally important but less urgent, he says, is a second set of questions related to ecology of the tick. "Does it move other organisms, like Ixodes scapularis ? What effect does it have on animal communities? At what type of densities does it live?" These are issues that can affect public health, "says Brisson

Meanwhile, our black-legged black ticks have been busy, transmitting Lyme disease in ever-increasing numbers, accounting for more than 80% of tick-borne diseases. Other more dangerous infections, such as the Powbadan virus and anaplasmosis, are also transmitted by these ticks. Brisson's research has examined what types of landscapes are most likely to harbor ticks and the role of certain host species in the transmission of different strains of Lyme bacteria. He adds that this information can be influenced by large-scale models of environmental characteristics that influence the risk of disease in humans, according to the authors.

"Emerging" Disease

Scientists Collect a Lot of Pathogens "Often, however, these infections are not new, they are new in the developed world," says Cherry.

"It may be an unpopular vision, but we have very little These diseases have always been affected by the disease, because they have mostly affected developing countries," she says [19659023]. Just look at Zika's epidemic from 2015 to 2017 to see how a virus formerly confined to Brazil has affected the continental United States. As this epidemic has pbaded, other infections, such as dengue fever and chikungunya, are circulating in the Caribbean. considered a threat to the United States, especially now that their vectors, some Aedes mosquitoes, have become well established here.

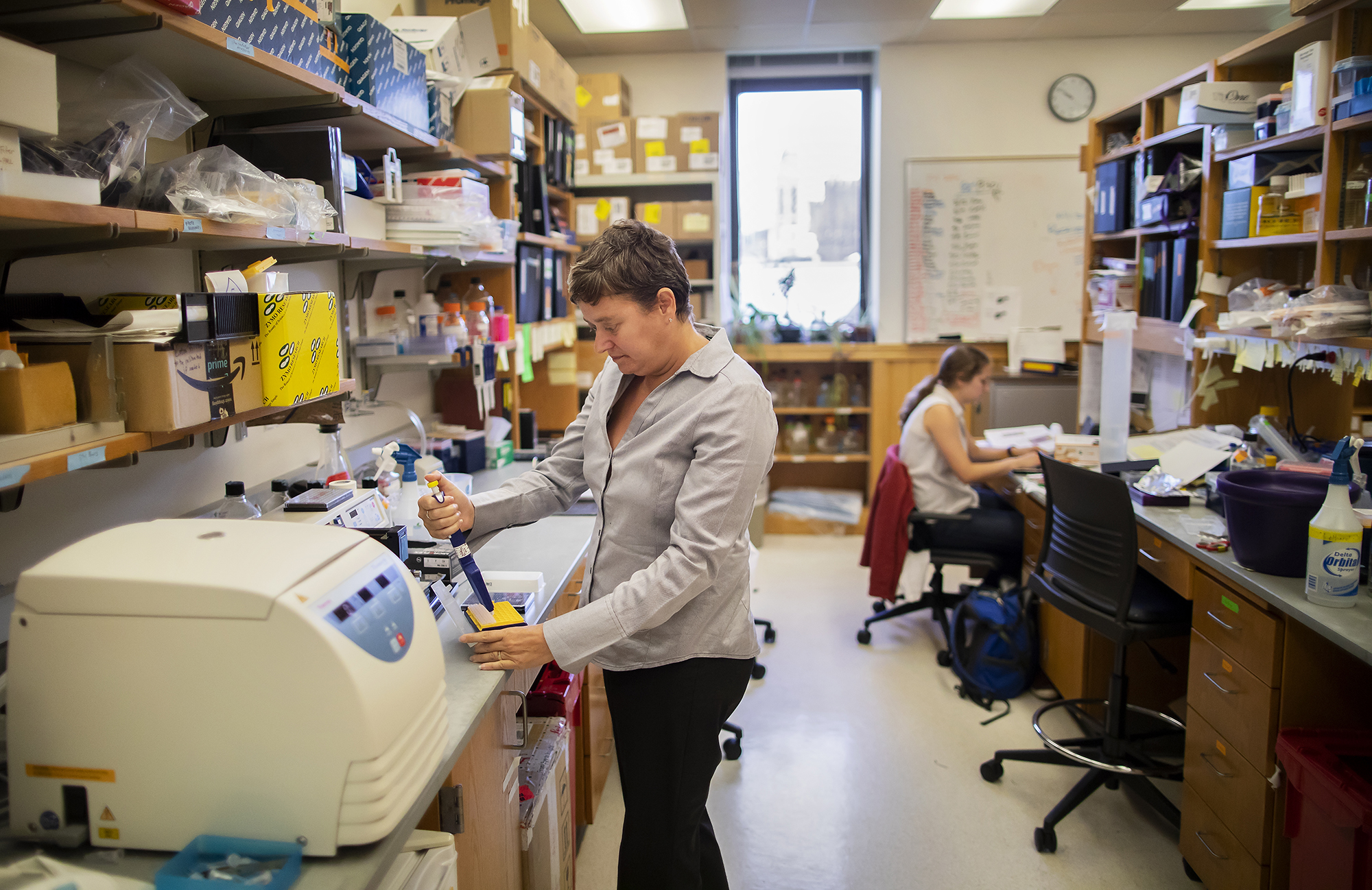

Cherry 's lab is studying these viruses and many others, looking for similarities in how these pathogens infect both mosquitoes and humans. The goal is to find potential drug targets to stop viral spread – ideally targets that could work to treat more of a disease.

Despite her interest in viruses, Cherry believes that currently the best strategy for combating these types of diseases is targeting vectors, not pathogens.

"When there was a yellow fever epidemic in the 1700s in Philadelphia, what did we do? We killed mosquitoes," she says. "What is the best tool for malaria in Africa?" Mosquito nets: When you retreat, we do not know much about how to treat these diseases, but we know how to kill and manage insects. "

C & # This may be an unpopular opinion, but we have very little understanding of these diseases because historically they have mostly affected developing countries.

Sara Cherry, Professor of Microbiology at the Perelman School of Medicine.

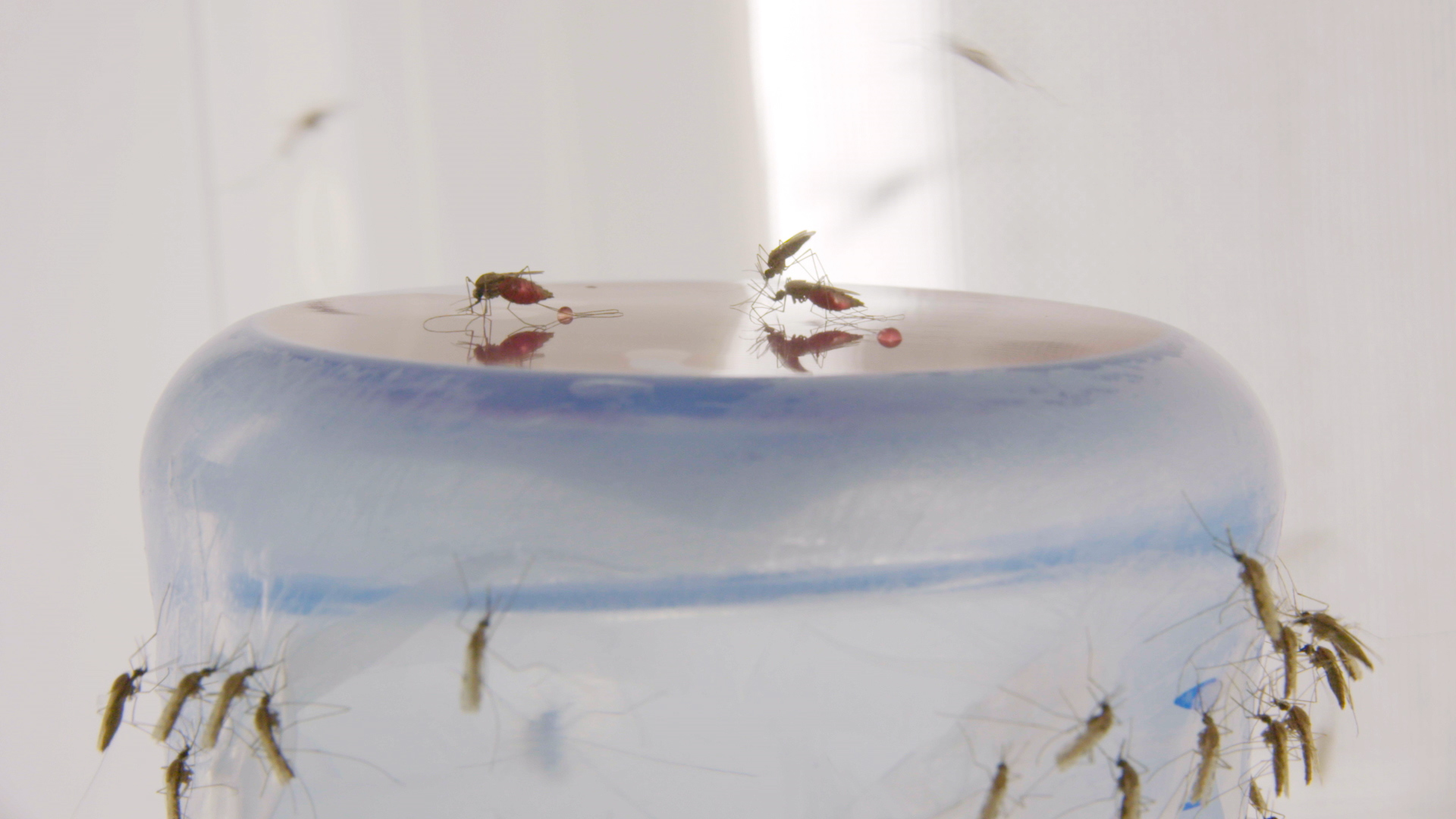

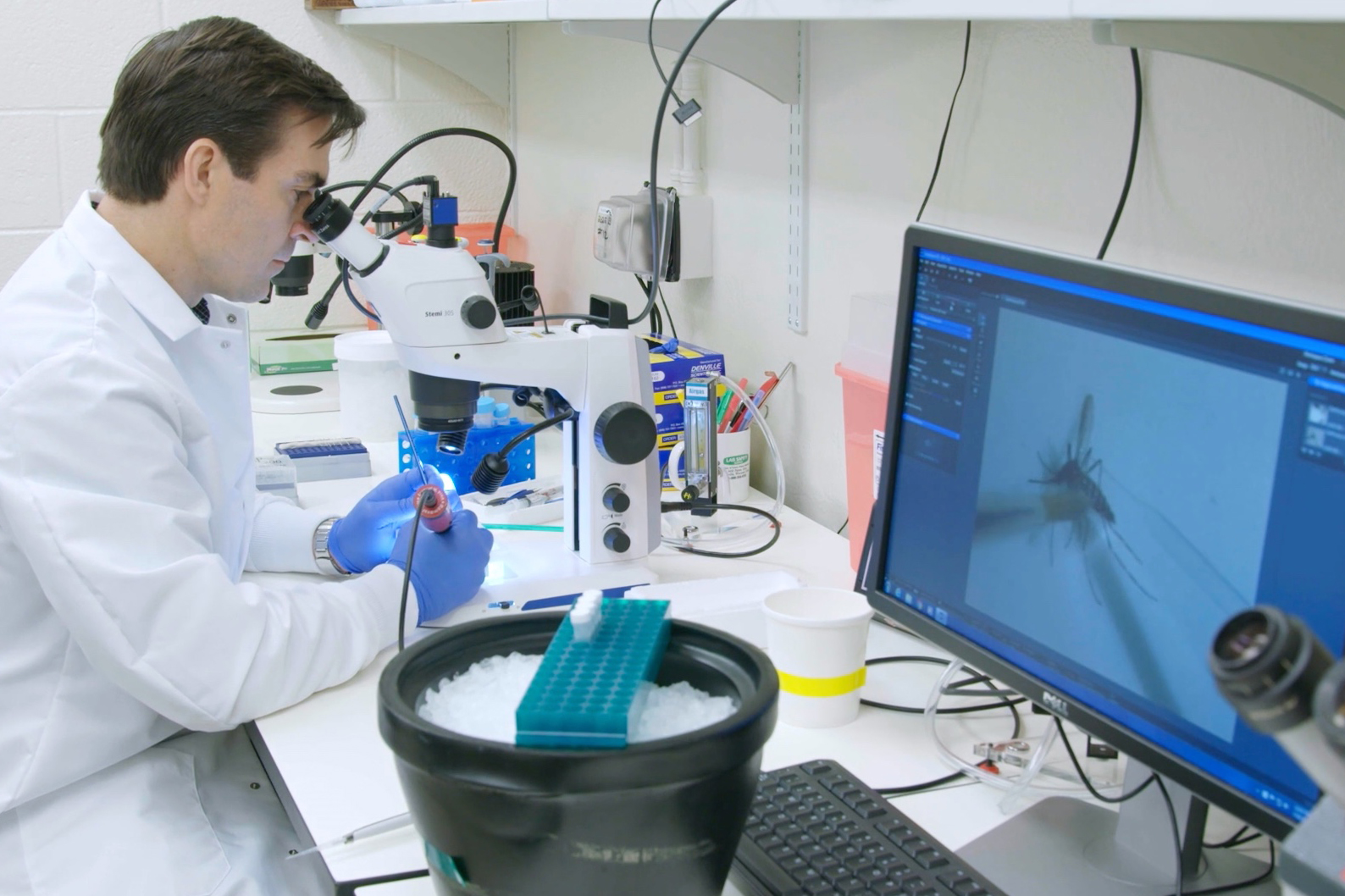

Michael Povelones is a researcher studying more and more sophisticated ways of handling mosquitoes for the benefit of human health. In a high-tech insectarium at the School of Veterinary Medicine, the Povelones Laboratory raises and infects mosquitoes with a variety of pathogens, and then studies how the immune system of insects fights invaders. The ability of insects to overcome or succumb to infection with, for example, malaria, has implications for their ability to transmit the parasite to humans.

A long-term possibility arising from Povelones' work would be to manipulate the mosquito's immune system so that the insect can no longer transmit the disease. Although we are far from the widespread spread of genetically modified mosquitoes, California has already seen the release of millions of mosquitoes infected by the Wolbachia a genus of bacteria that sterilizes mosquitoes, orchestrated by the sister company of Google, In truth. Kaycie Hopkins, a Penn graduate who has completed her Ph.D. working in the Cherry Lab, is one of the biologists who collaborate with software engineers and project automation experts at Verily.

"I am encouraged by the fact that companies and organizations are working on these large-scale efforts." says:

Mosquito-borne diseases are not just a problem for humans; they also infect wild and domestic animals. As part of a project undertaken over the last two years, Povelones and members of his laboratory have been studying what makes some mosquito species resistant to heartworm and other sensitive ones. While drugs already on the market protect animals from heartworm, Povelones says isolated cases of drug-resistant heart disease provide reasons to look for other strategies to tackle the parasite, in addition to swelling of infections in wild animals.

Brbad Teak

While news about scary diseases like chikungunya or anaplasmosis may seem overwhelming, the researchers point out that mere precautions can make a big dent in the risk of acquiring vector-borne infection:

- DEET high-potency insect repellents remain the norm for avoiding tick and mosquito bites. Other repellents, such as permethrin, are effective at keeping ticks away when they are applied to clothing

- When you venture into tick habitat, consider landscapes where forests encounter shorter vegetation, such as wooded trails. as well as insect repellents. Then do a careful examination of the ticks when you return home. "An entomologist with whom I spoke said that taking these tick precautions should be as anchored in the behavior of the belt as in the car," says Lok

- Eliminating stagnant water that can create habitats breeding near homes. A. aegypti and A. albopictus Larvae can thrive in an inverted bottle cap. "There is no point in hiring a company to spread insecticide on your property if you are not going to dump the water in your planters or if you leave the water your dog for days at a time, "says Cherry.

- Keep pets up-to-date on vaccinations and use FDA-approved medications or collars to prevent diseases such as heartworm and deter fleas, ticks and mosquitoes. In other words, continue to enjoy outdoor activities, keeping in mind that there is reason to be cautious.

"I do not think people should panic," said Cherry, "but I think they should learn that the world is getting small.You can not just bend your head and think that only people in d & # 39; 39, other countries are contracting these diseases, we are all in the same place now – it's a place now. "

Dustin Brisson is an badociate professor of biology at the School of Arts and Sciences .

Sara Cherry is a professor of microbiology at the Perelman School of Medicine

James Lok is a professor of parasitology at the School of Veterinary Medicine.

Michael Povelones is an badistant professor of pathobiology.

Home Page Photo: "Taking precautions is so crucial" when it comes to avoiding vector-borne diseases, says James Lok of Penn Vet. "But there is no reason for people to flee in terror or stop the activities they like to do."

Source link