[ad_1]

When I started my medical career in Hong Kong in the early 1980s, I chose to focus on hepatitis B, in part because it was very common and because the hepatitis C virus had not yet been discovered. I've witnessed the devastation caused by this virus – cirrhosis, liver failure and liver cancer – and the lack of treatments that we could offer to patients.

At the time, scientists knew that there was another type of hepatitis, but no one could identify it. we called it non-A, non-B hepatitis. I would have never imagined that during my career, I would witness the discovery of what was going to be known as Hepatitis C and the development of a cure for almost all patients with chronic hepatitis C in 2014.

Other researchers I've seen in the past 30 years are witnessing extraordinary progress that the field has made in the fight against cancer. Hepatitis C in a relatively short time. Initially, in the late 1980s, before a diagnostic test was available, some physicians began treating well-characterized cases of non-A, non-B hepatitis (C) with hepatitis C. interferon, a natural protein that the body produces to fight the virus. ribavirin, an antiviral drug. These medications were not developed specifically for hepatitis C, had to be administered as injections for 6 to 12 months, had many side effects and allowed to cure only half patients who have received treatment. It took more than two decades for the first direct-acting antiviral drugs to be approved by the FDA.

I remember the excitement when my colleagues and I tested one of the new drug combinations in patients and that the number of viruses went from over 1 million to less than 20 in two weeks. We published the results of our pilot study in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2012. Although the study only concerned 21 patients, it was considered a turning point because it was the first study to prove that a combination of oral pills without interferon could cure hepatitis C

The effective treatment of hepatitis C has become even more relevant today considering the l 39; recent increase in new cases of hepatitis C due to increased use of opioids.

A PRICE MEDICINE AND A NEW GENERIC

pill with two drugs that inhibit different stages of replication of hepatitis C was approved by the FDA in 2014. This pill is taken once a day for 8 -12 weeks, has little or no side effects and improved the cure rate to 90-95%. It was hailed as a magic cure, but it came with a price of $ 94,500 for a 12-week treatment. This has led many insurers in the United States and the national health departments of other countries to limit access to treatment.

Since then, several other pills combined with similar and well-tolerated cure rates have become available, and the cost has significantly decreased. In addition, low-cost generic medicines and special pricing arrangements are available in many resource-constrained countries.

While the current price of drugs for hepatitis C is still very high, it must be remembered that for 95% of patients, it's a cure. It does not look like drugs for many diseases that need to be taken for a long time, sometimes for the rest of the patients' lives. Indeed, a treatment against the hepatitis C virus has allowed some patients on the waiting list for a liver transplant to reverse their liver failure, which makes transplantation useless. This is good news not only for these patients, but also for others on the waiting list.

The remarkable success of hepatitis C treatment has revitalized efforts to find a cure for hepatitis B. Current treatments may suppress replication of hepatitis B virus but do not eliminate it. Most patients need to follow a long-term treatment to prevent hepatitis attacks when the virus recurs after stopping treatment

Photo: Xinhua / Sipa USA

Photo: Xinhua / Sipa USA

People receive vaccines against Hepatitis during the Global Campaign for Hepatitis 2017 in Kigali, Rwanda, July 13, 2017. More than 15,000 Rwandans have received free hepatitis vaccines

DEATH OF INFECTIONS WITHIN HEPATITIS. WORLD HEPATITIS B AND C

Learn from the experience of hepatitis C and better understand the biology of the hepatitis B virus and improved animal models, drugs that target different stages of the cycle hepatitis B virus are under development. Although the cure for hepatitis B will be more difficult as it can integrate into the patient's DNA, allowing him to escape the patient's immune response, I am optimistic that we will witness the availability of a new combination of drugs that will bring us closer to the goal of a cure for the hepatitis B virus.

But the news is not all positive . While death rates from HIV, TB and malaria have declined in recent years, mortality from hepatitis B and C has increased. Globally, it is estimated that 257 million people have chronic infection with the hepatitis B virus and 71 million have a chronic hepatitis C virus. Together, hepatitis B and C caused 1.34 million deaths in 2015. This led the World Health Organization to develop national plans to eliminate these two viruses by 2030. [19659003] The hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus contact with blood or body secretions such as sperm from infected people by sharing needles or badual exposure. But they can also spread through contaminated needles used for medical treatment, which continues to occur in many parts of the world. In addition, hepatitis B virus can be transmitted from infected mothers to newborns unless vaccination is given immediately after birth.

For the hepatitis C virus, about two-thirds suffer from chronic infection. For the hepatitis B virus, the risk of chronic hepatic infection decreases as the patient encounters the virus: 90% is infected during infancy; 20-30 percent if infected during childhood; and 2-5 percent if infected in adult life. Some people infected with the hepatitis B virus or the hepatitis C virus can heal on their own, but many of them turn into chronic infection (which lasts more than six months and often years or all of life). People with chronic infection are at risk of cirrhosis (severe liver injury), liver failure and liver cancer.

EPIDEMIC OPIOIDS, HEAD WITHOUT HOUSING CAPABLE OF MOUNTING TO HEP AND B

In the United States, the number of new infections by hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C decreases for many years, but this trend has reversed. years because of the opioid epidemic, as more and more people use injection drugs, share needles or other paraphernalia and engage in high risk badual behavior. This is especially true for hepatitis C, where the number of new cases in the last 10 years has more than doubled, highlighting the need for a preventative vaccine, which is a vital tool if we want to eliminate the disease. Hepatitis C. The increase in the number of new hepatitis B cases are smaller and are mostly seen in adults in their thirties, since most of the youngest have benefited from the vaccination against the hepatitis C. Hepatitis B virus.

When we talk about viral hepatitis, the focus is on hepatitis B and C because they can cause chronic infection, while hepatitis A causes only an acute infection and will not cause cirrhosis or liver cancer. However, as of the end of 2016, many US states have witnessed outbreaks of hepatitis A. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) received more than 2,500 cases of 39 Hepatitis A between January 2017 and April 2018, with risk factors in two-thirds of these cases being drug use or homelessness or both. In the state of Michigan, where I live, 859 cases of hepatitis A including 27 deaths have been reported between July 2016 and June 2018. We can prevent hepatitis A through vaccination and can be prevented from becoming infected. improvement of hygiene conditions.

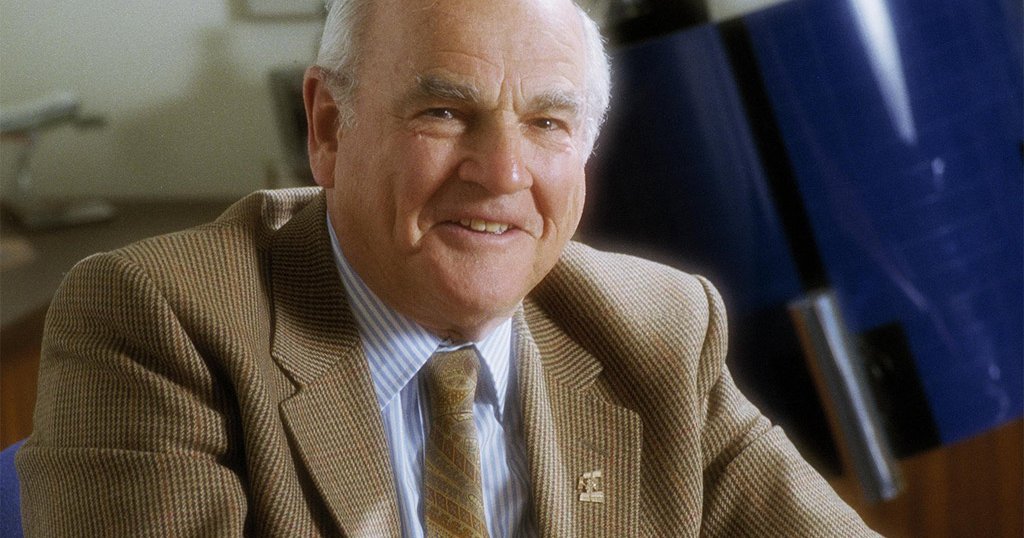

![]() As we celebrate World Hepatitis Day on July 28, the day chosen in honor of Dr. Baruch Blumberg, who received the Nobel Prize for discovering the hepatitis B virus, I am amazed We have come a long way over the past three decades and I am delighted to be not only an observer but also a contributor to progress. Our work is not finished. Much remains to be done to completely eliminate new cases of viral hepatitis and deaths due to chronic hepatitis B and C.

As we celebrate World Hepatitis Day on July 28, the day chosen in honor of Dr. Baruch Blumberg, who received the Nobel Prize for discovering the hepatitis B virus, I am amazed We have come a long way over the past three decades and I am delighted to be not only an observer but also a contributor to progress. Our work is not finished. Much remains to be done to completely eliminate new cases of viral hepatitis and deaths due to chronic hepatitis B and C.

Anna Suk-Fong Lok, Professor of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Source link