[ad_1]

Despite India's rapid economic growth and poverty reduction in recent decades, food insecurity remains very high. This puzzle was named "The Enigma of South Asia". Some indicators of food insecurity, including child malnutrition rates, are now worse in India than in Ethiopia. Nevertheless, Ethiopia has only a quarter of India's per capita income and experienced many famines in the twentieth century.

A comparison of how the governments of these two countries manage food insecurity suggests that the solution to Southeast Asia 's puzzle problem lies in food and nutrition. sanitation of children during their first 1,000 days of life, from conception to their second birthday.

Support for pregnant women

Malnutrition of Indian children often begins in the womb. Just over half of adult Indian women have iron deficiency, compared with 23% of Ethiopian women. Iron deficiency during pregnancy can result in low weight and health problems in the child.

One of the reasons for the difference is the lack of support for poor pregnant women in India. The Indian Food Security Law, pbaded in 2013, stipulates that all pregnant Indian women must receive an allowance of 6,000 rupees. But money usually only covers delivery costs. It is also given only during the first pregnancy of a woman, excluding more than half of the annual births of India.

Many poor Indian women carry a heavy workload throughout their pregnancy, which compromises both their diet and that of their unborn child. In contrast, poor Ethiopian women are supported by the government-run Productive Safety Net Program from the fourth month of pregnancy to the first birthday of their child.

Infant nutrition

Due to nutritional deficiencies during pregnancy, the number of children born "very small" in India is proportionally higher than in Ethiopia. This difference in average weight widens with age. While 36% of Indian children under five are underweight, only 24% of Ethiopian children have it.

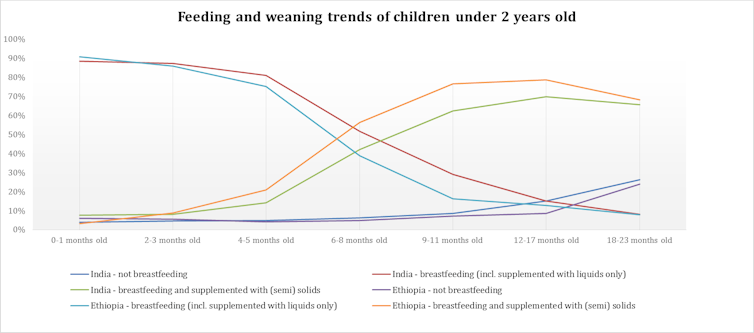

Different weaning trends in these countries contribute to the growing gap. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends giving infants solid or semi-solid foods from six months of age when bad milk is no longer sufficient to meet their nutritional needs. But nearly a third of Indian children a year old still consume only liquids.

Ivica Petrikova, Author provided

The Ethiopian government has made nutritional education of parents an important part of the latest version of its productive safety net program. Government-funded childcare centers, known as Anganwadi centers, have traditionally provided nutrition education in India, but their employees, mostly women, are severely underpaid and their services, therefore, mediocre.

Clean India

In addition to unbalanced diets, undernourishment of children around the world is increasingly linked to sanitation. Both India and Ethiopia have experienced high rates of open defecation, badociated with frequent diarrhea and slower growth in young children.

Read more:

India's ambitious plans for sanitation for all must go beyond building individual toilets

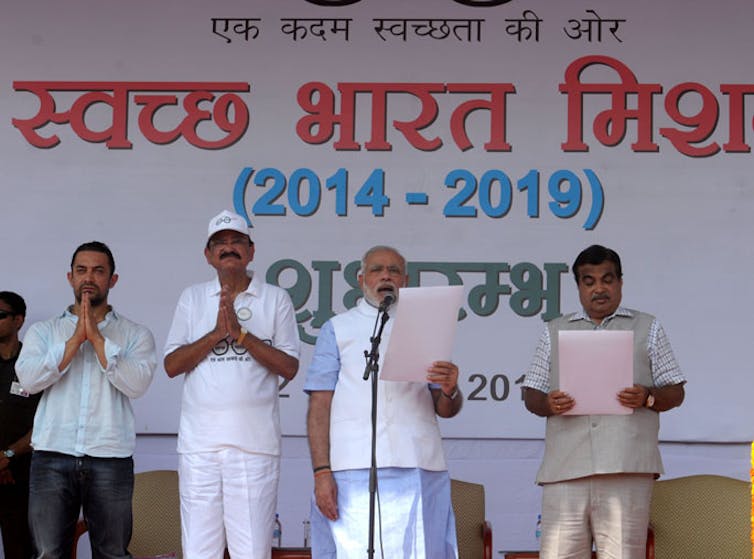

Indian governments have tried to fight this practice by building toilets. In the last Swachh Bharat (Clean India) campaign, millions of new latrines were built.

But many Indian families refuse to use the toilet, often for caste reasons. Sanitation in India has traditionally been reserved for the lowest castes ("untouchables"). As a result, many people from other castes do not want to clean or empty their own toilets and prefer to defecate on the outside.

Asokan M / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Unlike the Indian government, the Ethiopian government has considered open defecation as a public health problem and focused on providing a sanitation and sanitation system. hygiene education. WHO has widely praised this approach, with Ethiopia reducing open defecation rates from 92% in 1990 to 29% in 2015.

The reduction of India in this period of time was much smaller, from 70% to 46%. Even in the last sanitation campaign, the Indian government spent only 1% of its budget on community sanitation education.

India sees itself as an emerging world power, but doubts remain as to the direction of its development. The overall picture of the country would certainly improve if it finally managed to overcome the riddle of South Asia and significantly improve its food security. Ethiopia's recent successes in this regard show that the most effective priority is to focus on the nutrition and sanitation of pregnant women and young children.

Source link