[ad_1]

"If there was one word that would catch your attention in Mission Control, it would be the word" abandonment ". This word is never used casually and sounds literally in voice loops when it is transmitted to the crew, computer controllers and support personnel. . … during an abortion, your chances of going out alive are good if the abortion is done at the right time. If you are out of the calendar, your odds are not good 200,000 kilometers from home. "

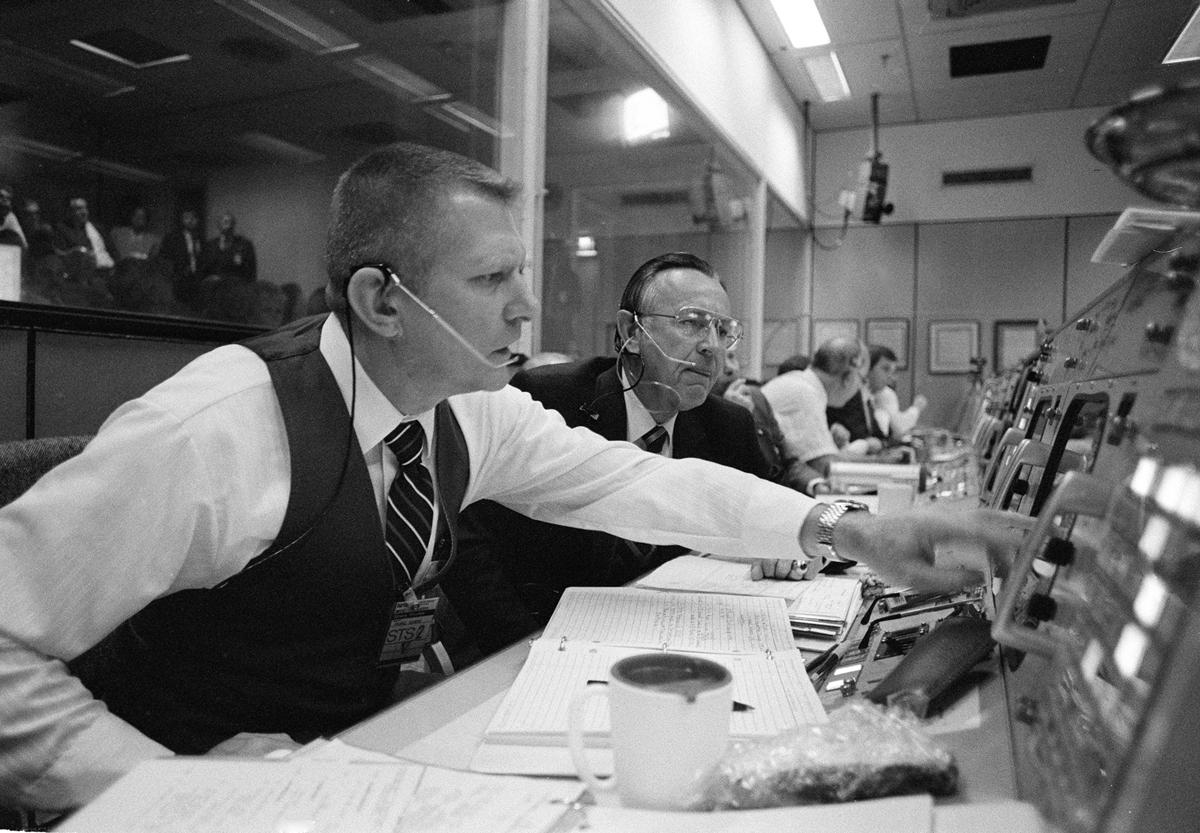

The bright and weighty people who work in mission control during the Apollo program are often treated like a hive and defending this presentation: they have worked as a remarkably complex group of complementary parts. None of them has had his work marked by large-scale parades like some astronauts. But the stakes were nevertheless high in their work and the burden of life at risk fell on them.

That's why the deaths of three astronauts during a test exercise for what was called Apollo 1 weighed heavily on everyone involved.

The Gene Kranz file

And Kranz has defined a philosophy for NASA from this tragedy. "Hard and competent" was his mantra, part of the commitment to push towards the moon but in a meticulously calibrated manner to maximize men's safety over all that fuel for rockets.

Kranz has emerged as a star among this set of mission control principles in a roundabout way. He possessed – and still possesses – a magnetic military manner; he knows the dramatic sound of his voice well. But Kranz's fame as a face of the 1960s, Mission Control, also owes some debt to "Apollo 13," the feature film by Ron Howard that describes the role of Kranz by Ed Harris, a charismatic and severe character.

"The failure of this film is not an option" of this film was created through the license to create a writer of something different, as Kranz said, and this has become an ubiquitous phrase. So much so that Kranz used it as the title of his 2000 memoir.

But Kranz gives the impression of a man whose manners before, during and after Apollo 13 were consistent.

When I spoke to Kranz a few years ago, he downplayed the importance of this remarkable work.

"We had a job to do," he says simply. But Kranz speaks with a touch of Midwestern grain to get an effect.

'I always wanted to fly'

Kranz grew up in Toledo, Ohio. There, he showed an interest in early flight and space flights.

"I've always wanted to fly," he wrote in his memoir. "I had my head in the clouds and my heart followed."

Kranz studied aeronautical engineering at the university and then joined the US Air Force reserve. He was stationed in Korea, where he had received an air traffic control mission – a demanding and tense job that emphasized preparation and accuracy. Like many other Americans, he felt a deep anguish when Russia launched its Sputnik satellite into space.

Kranz's subsequent orders sent him to Oklahoma to train with jet planes, which was a problem for him. Kranz asked to leave his active service and finally started working for McDonnell Aircraft. He was recruited for the Mercury Space Program, which initiated Kranz's long tenure at NASA.

At that time, he was married to Marta Cadena, whom he had met while he was stationed at Lackland Air Force Base in Bexar County. Marta began sewing vests for Kranz with the Gemini 4 mission. Kranz started wearing a new vest for each mission. The Smithsonian Institution now has its Apollo 13 vest.

Previously, Kranz was flight director for the Apollo 11 lunar landing, which meant he was at Mission Control as Eagle approached the moon's surface with his fuel running out fast.

Kranz then suggested to Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to "go bankrupt," according to James R. Hansen's biography in Armstrong, "First Man." "I had this feeling since they took over manual control," Kranz said. "These are the good ones for the job. I signed myself and said, "Please, God."

Kranz's fame will grow with the tense return of Apollo 13, in which an oxygen tank exploded and the complexity of the Apollo missions was again exposed.

Kranz never said: "Failure is not an option." When he was interviewed by screenwriters Bill Broyles and Al Reinert, who were working on the screenplay, he proposed a variant of the sentence.

Broyles took a spoken thought and turned it into poetry.

"Look, the guy was outstanding for working under pressure," said Reinert, who died in 2018. "Maybe it's Hollywood-y, but this line fits that character."

A new project

Kranz is now 85 years old and has been retired for a long time. But he kept a sense of pride for what he and his colleagues did with the Apollo program. Thus, in 2016, he found that the state of MOCR2, the mission control room that served as a groundhog for the Apollo missions, was inexplicably in poor condition.

In his dramatic voice, Kranz described the hall, its history and its status.

"It's a place of history," he said. "But what I see is a tired mission control, worn out with all his heart and soul. It is time to start the battle for its restoration. "

It was thus that a project began to lift the stained carpet, to replace flickering light bulbs and to give the room back its royal status, mission that should be completed in time for the fiftieth anniversary of the moon landing.

On the one hand, Kranz's efforts to draw attention to a ruined national monument seemed to be a contemporary and urgent problem. On the other hand, it was as if the flight director was doing what he did several years ago – assessing a situation that required action and determining the best course of action.

"Robust and competent" became a widespread expression of NASA after Apollo 1 and persisted throughout the program. And since then he became known as "Kranz Dictum".

[ad_2]

Source link