[ad_1]

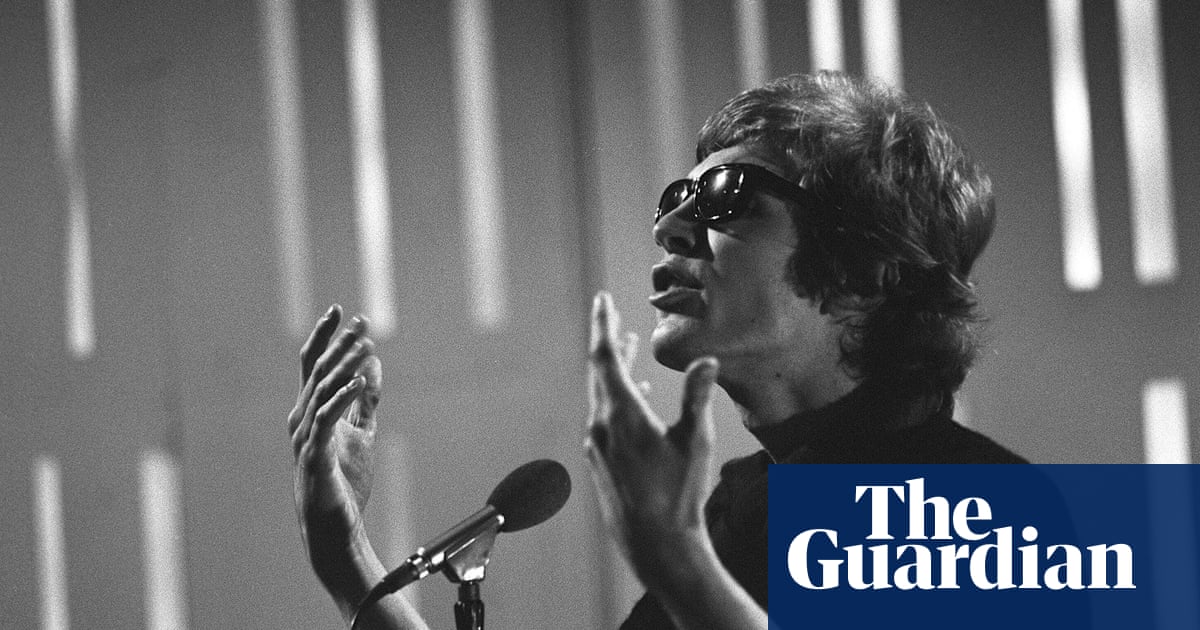

WWhen journalist Keith Altham visited London's Walker Brothers apartment in late 1965, he noticed a Victorian door hidden under one of the beds. He came from a house where Jack the Ripper had committed one of his murders. The forgotten heartbreakers had bought it at an auction. True or not, such a door opened the way to a plethora of horrible memories, inspired by an accumulation of fictions, odious acts of barbarism and insoluble mysteries. Perhaps this is where Scott Walker's extraordinary late contrarian style is.

His career embarked on a sunny schooner of orchestral ballads and ended with a twilight journey to the heart of darkness. As Walker declined in the mid-1970s, his work became an alcoholic blur of fake country and western themes, sleazy funk and light movies. But in the two years between Stretch and Nite Flights, published in 1978, Walker reads Chomsky's writings on US foreign policy and human rights abuses and goes out of the cabaret to get to the scene. the slaughter. In The Electrician, from Nite Flights, the nightmare of an executioner is temporarily transported into a rising orchestral rhapsody with Latin accents, before returning inexorably to the horror of the criminal chamber.

Edward Said described the "late style" as a form of fragments, expressing the idea of a crumbling civilization. The ornament and the harmony are rejected in favor of the dissonance and the silence. Late-style artists transcend conventionally acceptable, while stubbornly refusing to satisfy popular demand. Saorn quoted the vision of the disillusioned romantic Adorno "who exists almost ecstatically, but in a kind of complicity with new and monstrous modern forms – fascism, anti-Semitism, totalitarianism and bureaucracy". For me, this perfectly summarizes Walker's position from Tilt. Like a kid who gets you into a car, he has forced you into a scene of disorientation, trauma and violence. From the lounge chair to the electric chair.

The music that he laboriously created after Tilt, including The Drift, Bish Bosch, and Soused (with the American group Sunn O)))))), revealed a forbidden zone of voids and vacuums: magical realism, carvings and fragmented dystopias. The rhythm in Walker's late music is often heavy and lumpen, powered by drums and rock bass, or small cow bells or chimes. His songs were very controlled, including passages where time itself seemed suspended. He spoke of "big blocks of sounds", like the dense mass of sounds and drones that are in the work of Xenakis, Ligeti or Lachenmann. She is committed to the European avant-garde of the post-war, rather than the mechanical minimalism of contemporary American classical music.

As for his words, Walker once said to me, "It starts with something we know – a political problem – and then it slips into another world and into another. All sorts of disparate elements then take place. A single song can refer to molecular biology and sulphurous farts, or move from a dwarf of Attila's court to the Hun to a distant cluster of stars. His lyrics are full of unfamiliar words and technical terminology. Observe too his most opaque phrases ("Turnshoes", "Mouse Bells", "Tapir noshers" phuts "," Can not go through a brain man "," Ninon epicanthic picion button ") and you end up drifting off into a cognitive void. The only remedy is to follow the advice given in Climate of Hunter's Track Seven: "Try to find your own way."

From Tilt beats to Hammers of Blah's body through Herod's 2014 drone, if Walker's late sound is set, it's the tension between orchestrated textures, sound effects and explosions of overworked rock strength. . Walker is also harnessed to the familiar robotic repetition of industrial music. Although he is marketed as a rock artist, nothing has resembled Walker's late style, although artists such as Diamanda Galás, John Zorn, soundtracks inspired by Penderecki by Jonny Greenwood and Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson, recently deceased, have used subjects that merge with those of Walker. David Bowie, a long-time friend and admirer, used similar stylistic excesses, but never addressed Walker's immersion in the horror show of modern humanity in the same way.

Very little music from the last hundred years is as dark, bruised, deranged, insane, and devilish as Walker's. Still, there was also a lot of black and scatological humor, and the man was very different from the material. "Most of my songs," Walker told me once, "speak of frustration, of being unable to hold a spiritual moment, of losing it forever. Most of my songs are essentially spiritual. I try not to be too cynical about some things because it's too difficult otherwise. In Noel Engel's universe, "spiritual" should not be confused with "religious". But this great constellation of glittering ashes remains one of the most miraculous re-enactments in the history of popular music, a swan song perpetually on the wing, dragging feathers that never float on earth.

[ad_2]

Source link