[ad_1]

Unrecognized defense forces: researchers have identified a protective mechanism against intestinal inflammation in the human intestine, until now unknown. It is triggered by the stress of certain components of the cells of the intestinal mucosa. This causes the immune cells to release immunoglobulin A, which strengthens the intestinal barrier and prevents excessive inflammatory responses. The researchers now hope that this mechanism could also improve the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease.

Millions of people around the world suffer from inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis. In Germany alone, about 300,000 patients have these diseases, which are accompanied by diarrhea and abdominal pain. The causes of this intestinal inflammation are still obscure. Potential causes include not only genetic risk factors, but also intestinal flora and intestinal barrier disorders caused by environmental chemicals, disinfectants or nanoparticles.

Positive-effect stress

The researchers have now discovered an actor in the intestine, who can apparently have both positive and negative effects on the health of the intestines. It is the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) – a branched membrane network in the cells of the intestinal mucosa. It is sensitive to stress caused by environmental factors and can therefore promote inflammatory bowel inflammation.

But it turns out that the stress of emergencies can also protect the bowel from inflammation. For their study, Joep Grootjans of Harvard Medical School and his colleagues examined the consequences of emergency stress in mice. They found that the cells of the intestinal mucosa were stressed, they specifically recruited immune cells from the abdominal cavity. "Our data shows that the intestine is actively communicating with these cells during the stress of emergencies via previously unknown factors and thus gets help from a distance," says Niklas Krupka, a colleague from Grootjan.

The antibody as a protective force

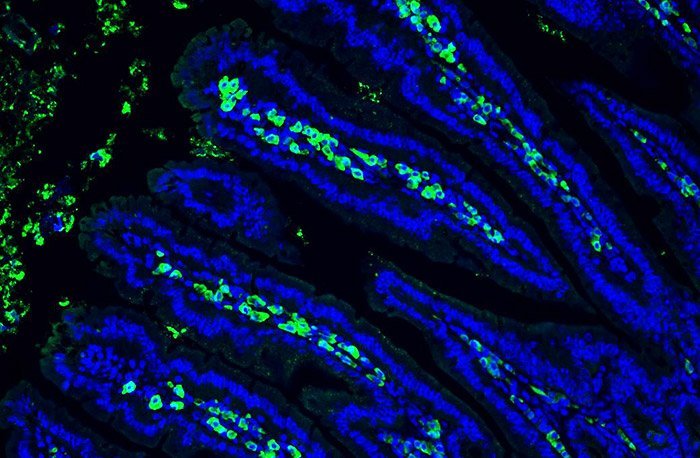

What is exciting is that the induced plasma cells then began to release immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies – which had a positive effect on the intestine. Because the increased presence of these immune proteins enhanced the protective barrier of the intestinal mucosa and could protect mice against excessive inflammatory responses. On the other hand, if the researchers disrupted the production or transport of antibodies, the protective effect did not materialize and intestinal inflammation developed.

Interesting too: this protective mechanism is apparently independent of the intestinal flora. As scientists have discovered, this immune response also occurs in mice totally devoid of germ: "It is only by genetically generating that ERs were generated in intestinal cells that we could induce a significant increase in IgA production in germ-free mice, "says Krupka. "This shows that we are dealing with a fundamental protective mechanism of the intestine that does not even require natural microbial colonization."

New approach to the treatment of intestinal inflammation

Grootjans and his team believe that this protective mechanism is also present in the intestine. They found an indication in the intestinal biopsies of people who had a variant of the ER stress-promoting gene: even with them, there were more IgA-producing cells in the intestine. This may indicate that this protective response is genetically weaker or even absent in humans with inflammatory bowel disease.

The researchers hope that the knowledge gained in the future can be used for new approaches to the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease and are already planning further studies. "Emergency stress in the intestinal mucosa can fulfill a useful function – similar to the term borrowed from psychology," Eustress ": a stress-inducing stimulus that positively affects the body, however," states Krupka. (Science, 2019, doi: 10.1126 / science.aat7186)

Source: University of Bern

March 1, 2019

– Nadja Podbregar

Source link