[ad_1]

Precision medicine is the dream field for human health – drugs and treatments that take into account an individual's individual DNA patterns, as well as his lifestyle and his environment, would be without doubt better suited to the needs of each person. Nevertheless, while precision medicine aims to help everyone, current research has a major disadvantage: it relies heavily on the genes of predominantly white and European people.

According to Sandra Soo-Jin Lee, anthropologist and bioethicist, this issue has ethical and scientific implications. She is leading the new division of ethics at Columbia University Medical Center and is leading a $ 2.8 million study, funded by the National Institute for Human Genome Research, which will examine research on the medicine of accuracy in academic medical centers in the United States and help researchers understand how to expand the diversity of genetic data collected.

I think we will see that the way people are treated in the health care system affects their attitudes towards research. – Sandra Soo-Jin Lee, Bioethicist, Columbia University

Lee recently wrote on ethics in personalized medicine research for Science magazine, and we explained why growing diversity is important. The interview has been changed for its length and clarity.

Where are we now in research on precision medicine? In your article, you say that it is the "first phase".

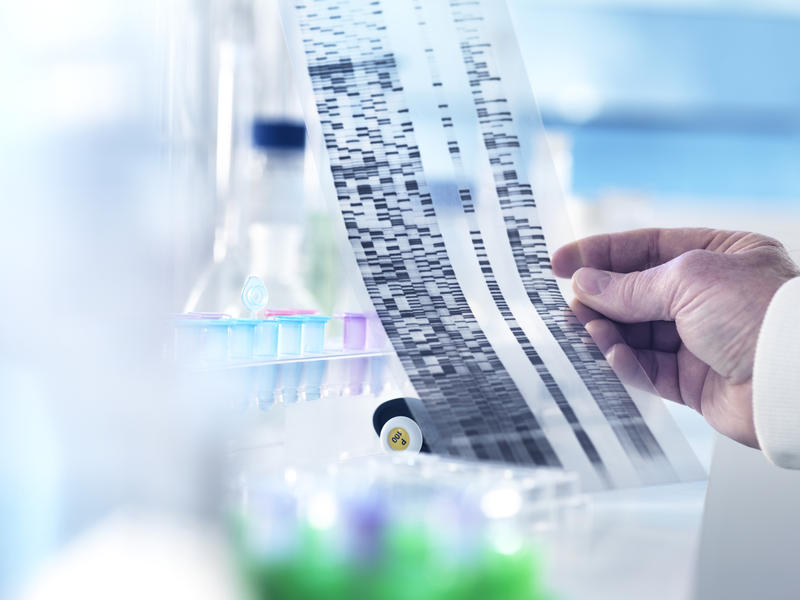

Precision medicine relies on the accumulation of a large number of biological data and samples (such as blood, urine, saliva, and health surveys) and individual access to medical records . In the last two decades – since the human genome project, completed in 2003 – our company has invested in all kinds of data collection activities.

Some of them have been on a large scale … like the All of Us program, organized by the National Institutes of Health, which aims to recruit one million people to share their genetic information. and sanitary for research. Other organizations have created their own bio-repositories that will likely be used for research that will improve precision medicine.

So we are building the infrastructure for the research sector, essentially creating these large libraries of information and individual samples, and making decisions about how they will be stored and preserved. And this has raised many questions about how to recruit people ethically into these types of large-scale projects, when it's hard to determine how the samples and data could be used at the same time. to come up.

What is the current diversity of the gene pool, in terms of what is collected for research?

At present, our genetic resources are primarily made up of DNA of people of European descent; the proportion of non-European ancestry represents less than 20%, in most studies. So it's a bias that exists in our deposits right now.

The scientific problem is that it does not represent the diversity that could be seen in the human species. Due to the migration of human populations around the world, African populations reflect a greater diversity band than other populations, yet this is not reflected in our genetic resources.

Is the lack of diversity a problem in US research institutes or is it global?

This is a very good question, especially since there is a lot of data sharing and samples around the world. There are some genome research centers around the world. … [They] tend to be in the United States, Europe and East Asia. So I think the tilt is actually global, in the sense that the researchers who did this type of work mainly sampled people of European descent and we just do not see the kind of diversity that you would see if you were going to do it systematically around the world.

There are exceptions – some large-scale efforts in Africa, funded by federal agencies such as the NIH, are trying to address some of the problem we're seeing. But overall, it is a global problem.

What are some of the reasons why the gene pool is predominantly white?

Emphasis has been placed on the historical exclusions of certain populations. But I think this formulation of the problem may not take into account the fact that people have always been included – but in an unethical way.

The Tuskegee syphilis study, as well as recent studies with tribal biological samples from Havasupai, are examples.

These are cases in which populations have been enrolled in studies but have not been treated in an ethical manner. This creates a mistrust towards the research enterprise. …

Then, one wonders if research, even if it produces more targeted interventions on individuals, will be distributed fairly and equitably to all populations. Will they be within the grasp of those who might not be able to afford the health care they receive now?

In your article, you mention the recent claims of white nationalists who consider descent to claim racial superiority. Are there any valid reasons why people are wary of the intent and use of medical information?

Absolutely, and I think this particularly affects research on precision medicine because it requires such intrusive data collection.

"Who will use it? What will be shared? Will I have my say if I do not feel comfortable with how it will be used in the future? ;to come up?" I do not think we are ready to answer some of these questions.

The lack of information and accountability makes individuals – especially those who are most vulnerable in our society – very uncomfortable. And this is not unreasonable for them to be concerned.

What does meaningful and meaningful diversity and inclusion look like?

I think it starts with a willingness on the part of researchers to address the role of history and the continuing mistrust of certain groups with respect to research.

There is also this tendency to believe that there is a clear boundary between clinical care and research; I think we will see that the way people are treated in the health care system affects their attitudes towards research. There can be points of intervention and improvement.

To be able to expand our framework to reflect on the implications of this research on collective harms and benefits will be very important.

And I think we need to go beyond informed consent – a practice in which research subjects discover the risks and benefits of participating in a study before deciding to sign – by thinking about control protections that would hold desire of participants to make sense. responsibility for how their biological samples and data are used and shared. We need to make people feel that their interests and concerns are taken into account, beyond just recruiting.

Why is it important for the gene research pool to diversify further? Does gene pool diversification really benefit underrepresented populations?

We invest publicly in these resources. And the goal is to address health disparities, which have been a long-standing concern in our society. Health disparities are the largest among the underrepresented in our research databases. … and this becomes an important moral problem.

The greatest diversity would be introduced by African, Hispanic and Latin American origins. But it's not as if the benefits would only benefit these populations – it benefits everyone.

If we only use the current database, we may not identify the rare variants that would be identified if we had a broader spectrum of diversity in the genetic databases. … Perhaps [there are] It was thought that it was perhaps only because it was more common in this particular population and was therefore a confounding factor.

In recent studies, where scientists are using more varied resources, they have been able to find different variants that they were not aware of that might be important to understanding the disease. So there is good reason to think that a greater diversity will make us more precise regarding our precision medicine.

9(MDA3OTAzNzgzMDEzMTIyMTYyODIxZDdjYg004))

Source link