[ad_1]

If a person's liver begins to deteriorate, the only medical option we currently have is to replace that vital organ, partially or totally. But now, the discovery of a new type of liver cell has prompted scientists to consider a less invasive and less risky alternative.

By sequencing a cell in the liver tissue of the human fetus, the researchers identified a previously unknown cell that could possess stem cell-like properties. If the new discoveries are up to their potential, the authors hope that this type of cells could one day help regenerate damaged livers without the need for a transplant.

"For the first time, we have discovered that cells with true stem cell-like properties may well exist in the human liver," says hepatologist Tamir Rashid of King & s College London.

"This, in turn, could provide a wide range of regenerative medicine applications for treating liver diseases, including the possibility of circumventing the need for liver transplants."

Using monocellular RNA sequencing, Rashid and his colleagues explained the various cellular components present in the human fetal liver and, later, in the adult human liver.

In both cases, although their expression is slightly different, the team found the presence of a specific type of cell, here called hepatobiliary hybrid progenitor cell, or HHyP for short.

By examining these cells more closely, the study authors found that human HHyP had a striking resemblance to some mouse progenitor cells, which have been shown to quickly repair the liver from the liver. a rodent after a serious injury. Until now, however, no parallel of this type has yet been found in humans.

"In utero uptake of a human liver progenitor state provides an unparalleled and unexplored insight into the true mechanisms of human liver development," writes the team in its study.

The terms "progenitor cells" and "stem cells" are biological terms sometimes used interchangeably, but there are important differences. Progenitors work in the same way as stem cells in that they are able to differentiate into another type of cell.

Unlike stem cells, progenitors can only undergo a finite number of replications and are limited to making a few different cell types.

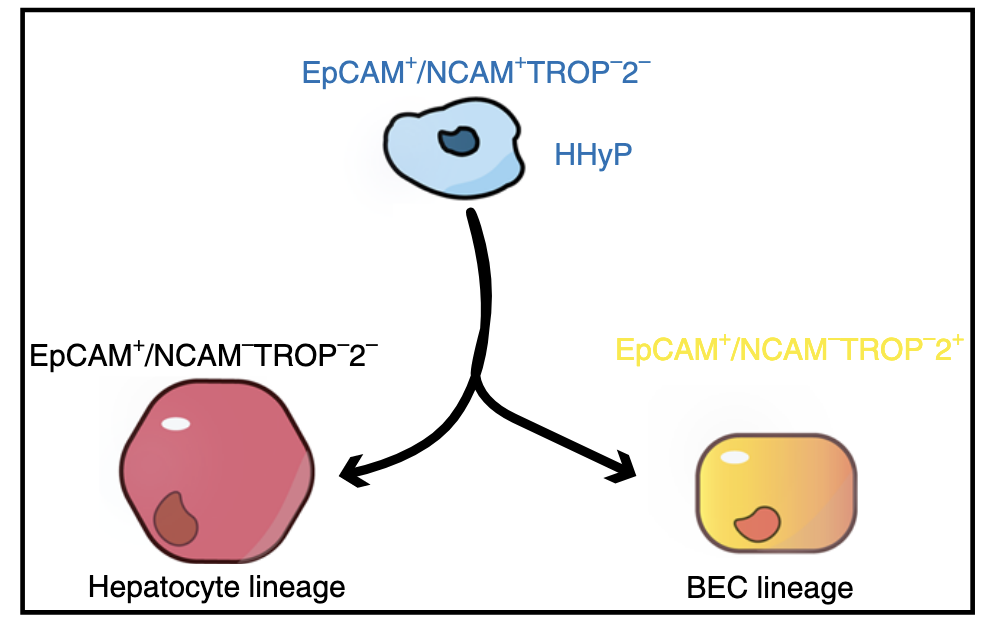

In this case, newly discovered HHyP appear to be a precursor of two major liver cells, distinct from all others: one for the liver, called hepatocytes, and another for the bile duct, called cholangiocytes or BEC.

(Segal et al., Nature Communications, 2019)

(Segal et al., Nature Communications, 2019)

After acute liver injury in rats, recent studies have shown that both types of cells can restore liver mbad and function. In addition, when one of these cells is impaired in rats, the other type can intervene to fill the void.

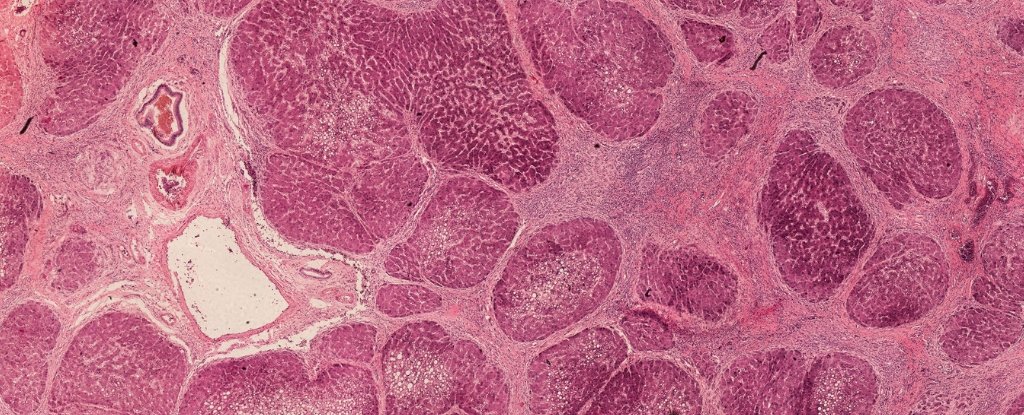

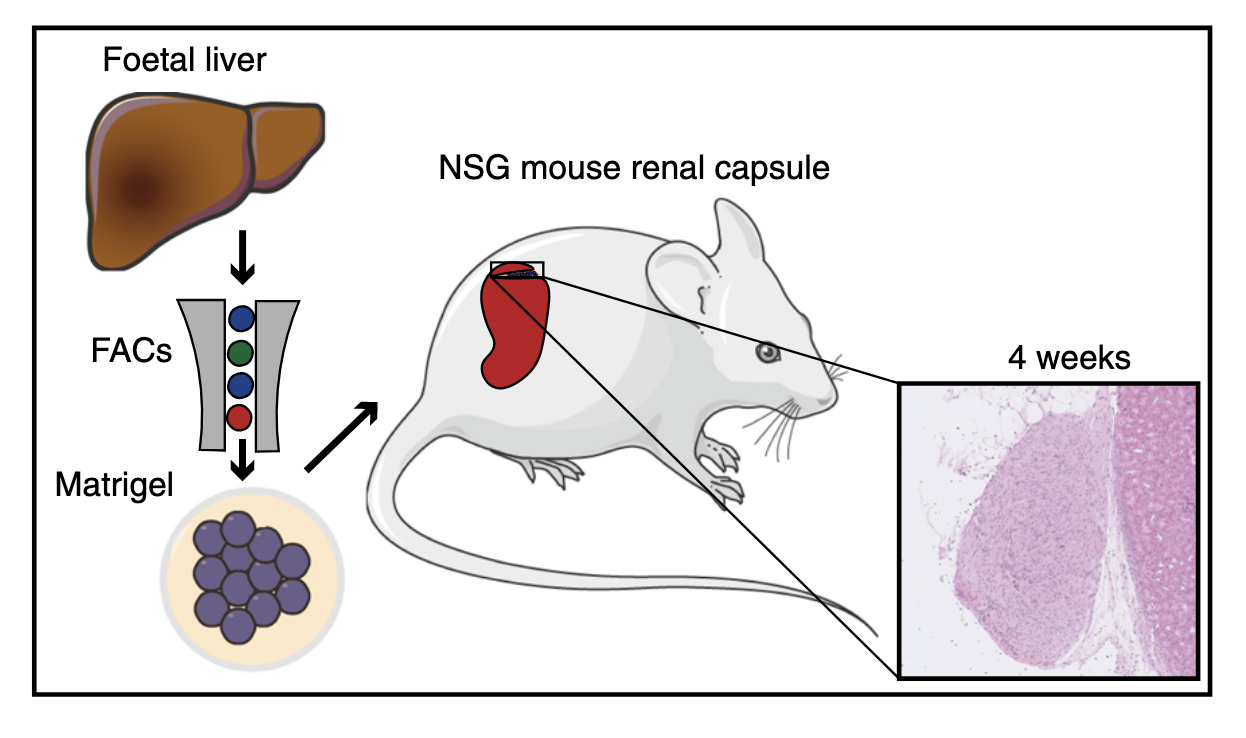

To see how they manage in a living animal, the researchers injected human fetal HHyP into the kidney capsule of immunodeficient mice. After only four weeks, the results show that the HHyP cell population does not only proliferate in these rodent kidneys, it also differentiates into hepatocytes.

(Segal et al., Nature Communications, 2019)Obviously, we are still far from using these progenitors to replace liver transplants in humans, but these preliminary results are a fascinating progress. And the authors of the study are already thinking about the possibilities.

(Segal et al., Nature Communications, 2019)Obviously, we are still far from using these progenitors to replace liver transplants in humans, but these preliminary results are a fascinating progress. And the authors of the study are already thinking about the possibilities.

If the induced pluripotent stem cells can be transformed into HHyP cells and then transplanted into a damaged liver, the team thinks that this could help regenerate the tissue lesions. The other solution is slightly more radical and would somehow trigger these cells while they are still in the liver of an adult person.

"We now have to work quickly to discover the recipe for converting pluripotent stem cells to HHyP so that we can transplant these cells into patients at will," Rashid says.

"In the longer term, we will also try to see if we can reprogram HHyP in the body using traditional pharmacological drugs to repair diseased livers without transplanting cells or organs."

This research was published in Nature Communications.

Source link