[ad_1]

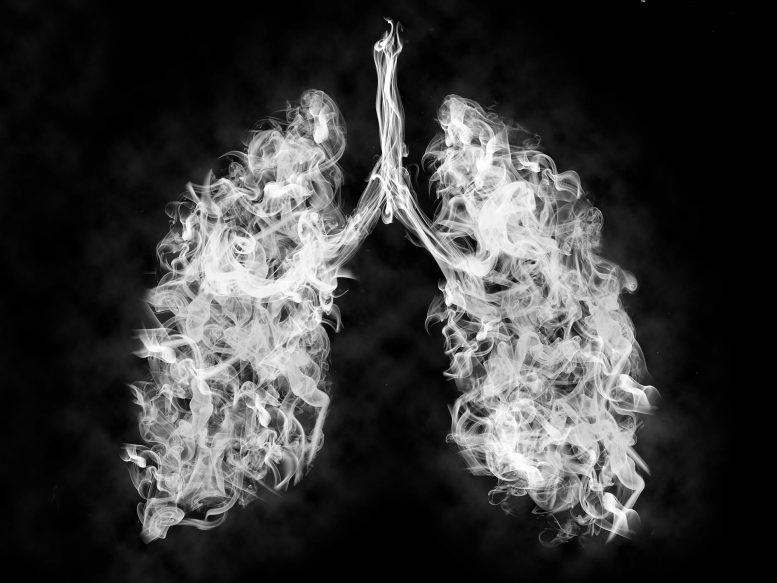

Smoking marijuana increases the levels of potentially harmful chemicals, but to a lesser extent than smoking; Exposure to a toxic chemical associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease increases with smoking.

Scientists from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have found new evidence of the potential health risks of chemicals in tobacco and marijuana smoke.

In a study published online today by ClinicMedicine, researchers report that people who smoked marijuana only had several toxic chemicals related to smoke in their blood and urine, but at lower levels than those who smoked both tobacco and marijuana or tobacco only. Two of these chemicals, acrylonitrile and acrylamide, are known to be toxic at high levels. Investigators also found that exposure to acrolein, a chemical produced by the combustion of various materials, increases with smoking but not with marijuana and contributes to cardiovascular disease in tobacco smokers.

The results suggest that high levels of acrolein may be a sign of an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and that reducing exposure to the chemical could reduce that risk. This is especially important for people infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, given the high rates of smoking and the increased risk of heart disease in this group.

Marijuana plant.

“Marijuana use is on the rise in the United States, with a growing number of states legalizing it for medical and non-medical purposes – including five more states in the 2020 election. The increase has renewed concerns about the effects health potentials from marijuana smoke, which is known to contain some of the same toxic combustion products found in tobacco smoke, ”said lead author of the study, Dana Gabuzda, MD, of Dana-Farber . “This is the first study to compare exposure to acrolein and other harmful smoke-related chemicals over time in exclusive marijuana and tobacco smokers, and to see if these exposures are linked to cardiovascular disease. “

The study involved 245 HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants in three studies of HIV infection in the United States. (Studies involving people with HIV were used due to the high rates of smoking and marijuana in this group.) Researchers collected data from participants’ medical records and survey results and analyzed their blood and urine samples for substances produced by the breakdown of nicotine by burning tobacco or marijuana. Combining these datasets allowed them to trace the presence of toxic chemicals specific to smoking or marijuana and see if any were associated with an increased risk of heart disease.

The researchers found that participants who smoked marijuana exclusively had higher blood and urine levels of several toxic smoke-related chemicals such as the metabolites of naphthalene, acrylamide, and acrylonitrile than non- smokers. However, the concentrations of these substances were lower in marijuana smokers only than in tobacco smokers.

The researchers also found that acrolein metabolites – substances generated by the breakdown of acrolein – were elevated in tobacco smokers, but not in marijuana smokers. This increase was associated with cardiovascular disease, whether individuals smoke tobacco or have other risk factors.

“Our results suggest that high levels of acrolein can be used to identify patients at increased cardiovascular risk,” Gabuzda said, “and that the reduction in acrolein exposure due to smoking and other sources could be a strategy to reduce the risk. ”

Reference: January 11, 2021, ClinicMedicine.

DOI: 10.1016 / j.eclinm.2020.100697

The first author of the study is David R. Lorenz, PhD, of Dana-Farber. Co-authors are Vikas Misra, MSc, Sukrutha Chettimada, PhD, and Hajime Uno, PhD, of Dana-Farber; Lanqing Wang, PhD, Benjamin C. Blount, PhD, and Vi? Ctor R. De Jesu? S, PhD, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Benjamin B. Gelman, MD, PhD, University of Texas; Susan Morgello, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine; and Steven M. Wolinsky, MD, of Northwestern University.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01 DA040391 and DA046203); National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (grants U24MH100931, U24MH100930, U24MH100929, U24MH100928, U24MH100925, MH062512, HHS-N-271-2010-00036C and HHS-N-271-2010-00036C, and000030HSN271) National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grants U01-AI35039, U01-AI35040, U01-AI35041, U01-AI35042 and UM1-AI35043); the National Cancer Institute; National Institute on Drug Abuse; and National Institute of Mental Health. MACS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000424.

[ad_2]

Source link