[ad_1]

Photographer: Matt York / AP

Photographer: Matt York / AP

A new drug for Alzheimer’s disease is on a torturous trajectory for the U.S. market, and while many patients hail the approval as a major breakthrough, it could also reignite concerns about the scientific integrity of regulators.

Biogen Inc. said on Friday that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration was expanding its review of aducanumab, an investigational therapy that patients and their families see as a potential lifeline. But the agency’s story of the drug’s efficacy data echoes a five-year-old decision to support treatment for childhood muscle wasting disease, which remains controversial.

FDA watchers and its own staff fear the regulator and its executives are developing a model for approving drugs of questionable value for devastating conditions due to public pressure. His swift clearance of Covid-19 treatments such as hydroxychloroquine which were touted by former President Donald Trump and later deemed ineffective is amplifying concern.

“No one will benefit, except maybe the shareholders, from having a product on the market that doesn’t work,” Caleb Alexander, a Johns Hopkins University epidemiologist and FDA adviser who doesn’t believe the available evidence supports Biogen’s drug, said in an interview.

Read more: Trump’s touted plasma therapy shows no benefit, researchers say

The FDA and Biogen declined to comment on their interactions.

Investor interest was piqued on Friday when the agency delayed a decision on whether to approve the drug for three months until June 7, suggesting that Biogen’s application is under further consideration . Biogen and partner Eisai Co. says in a statement they gave to the agency more analysiss and data that will take some time to review.

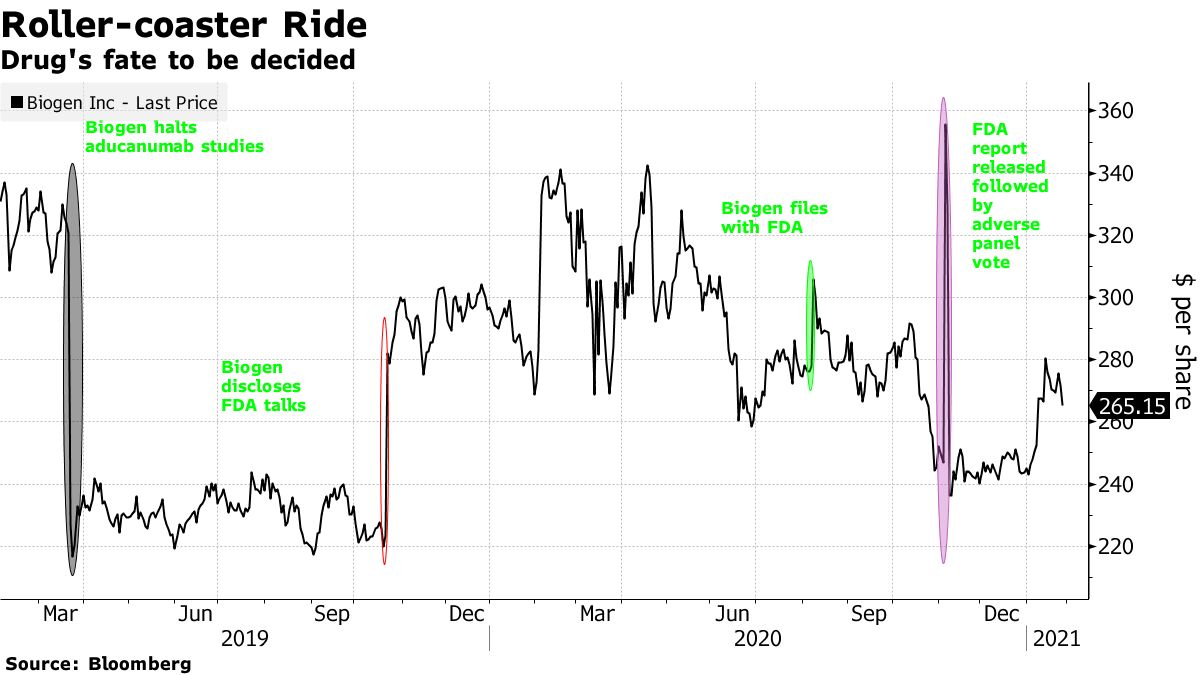

While the news met with a mixed response from analysts, shares of Biogen rose 5.5% on Friday. They’ve been having a roller coaster ride since early 2019 when Biogen, based in Cambridge, Mass., Stopped clinical trials with aducanumab because it didn’t work in patient testing. The stock shot up later the same year when a re-analysis of one of the halted trials showed a glimmer of success.

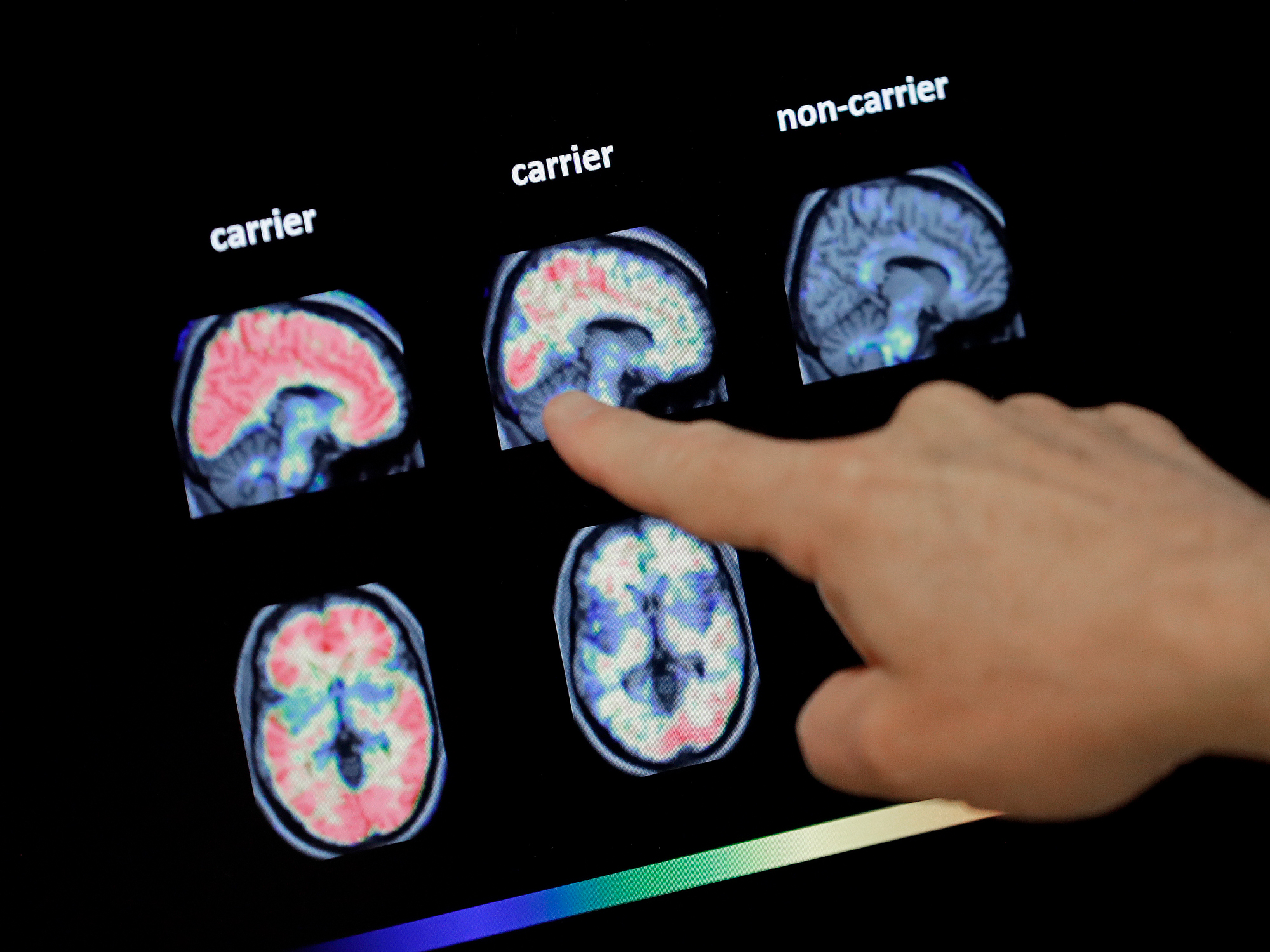

Aducanumab removes abnormal protein deposits called amyloid plaques from the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. It is supposed to be used years before the onset of potential symptoms, aiming to delay the decline of patients.

Revived Hope

But the debate has revolved around whether plaque removal offers any benefit. Attempts to develop similar drugs have failed, although aducanumab and potentially promising data from an experiment drugs from Eli Lilly & Co. have revived some hope.

As America’s population ages and Alzheimer’s rates rise, effective treatment would be a major breakthrough. The 2019 reanalysis prompted Biogen to seek guidance from the FDA, resulting in year round collaboration to further analyze data from the two trials, according to a document the agency and Biogen prepared ahead of a November meeting of agency advisers.

“Given the unmet medical need and the unique nature of the data,” the regulator met four times with Biogen between June 2019 and June 2020 to discuss the studies, the document said. At the final meeting, they discussed the possibility of Biogen submitting an application for approval of aducanumab.

Billy Dunn, acting director of the Bureau of New Drugs’ Bureau of Neuroscience at the FDA, worked with the company on the November document evaluating the drug. Usually the regulator and drug companies write separate briefing notes about a drug’s data before advisory committee meetings, with the FDA taking a very critical look at them.

“Our group has been testifying for five decades prior to the FDA advisory meetings,” said Michael Carome, director of Public Citizen’s health research group, a government watchdog. “We have never seen such a briefing document.”

The FDA refused to make Dunn available for an interview.

When the FDA’s external advisers met in November to consider recommending the drug for approval, agency staff presented them with the glowing report. The evidence from the somewhat positive clinical trial was “strong and exceptionally convincing,” the document said. He rejected the unfavorable results of a second identically designed trial, saying they did not show the drug to be ineffective.

Read more: Biogen Rises After FDA Reviews Back Alzheimer’s Drug

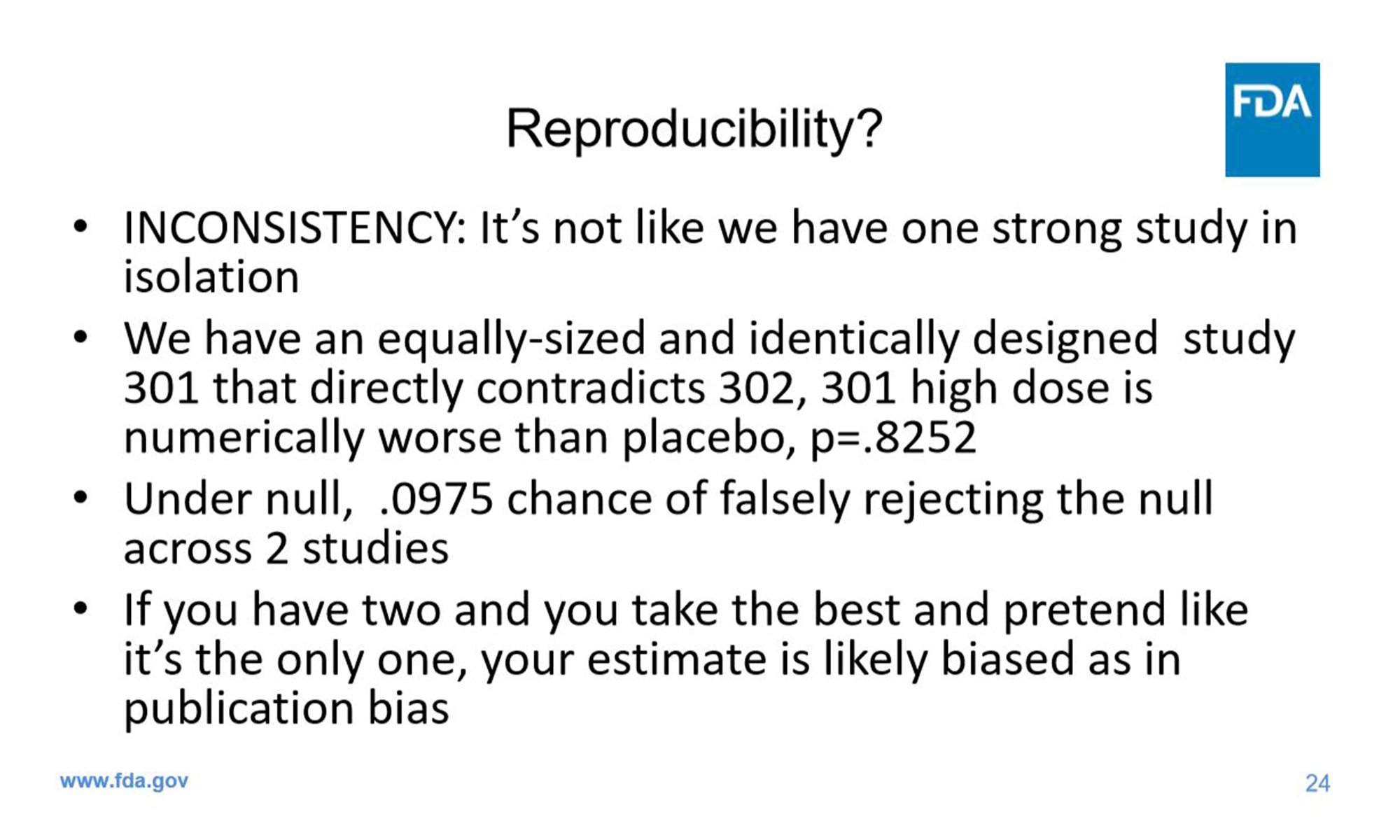

Tristan Massie, an FDA statistician, was a dissenter. “Excluding data from a large trial without sufficient justification is not scientific, statistically inappropriate and misleading,” he said in a presentation to members of the advisory committee.

Presentation slide Tristan Massie, FDA statistician, prepared for the November 6, 2020 agency advisors meeting to discuss aducanumab.

But Massie didn’t have much time to express his point of view at the November meeting, as questions were directed to biotech scientists.

Agency reprimanded

“I thought the most shocking thing was when one of the panelists asked a statistical question and Dunn responded by saying, ‘You know I’m not a statistician but maybe Biogen could answer'” said Brian Skorney, a Robert W. Baird. & Co. analyst who watched the meeting.

The panel’s discussion and recommendation against aducanumab was “a resounding and almost unanimous rebuke” of the drug, Biogen, and the FDA’s clinical critics, wrote Cowen analyst Phil Nadeau at the time. But the drug could still be eliminated. The agency does not have to follow the recommendations of its advisers.

Biogen declined to say whether it submitted data to the FDA from another trial, called Embark, which began in March 2020. The study is not the most rigorous clinical study format because it does not include a comparison group of patients who received a placebo.

About 5.8 million Americans live with Alzheimer’s dementia, and the number is expected to climb to almost 14 million by 2050, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. Patients and their families are looking for anything that can help stop the insidious spread of the disease.

Photographer: Patricia Lake / UsAgainstAlzheimer’s

“If you had a 50/50 chance that this drug would work for me, it’s better than the zero chance I have today,” said George Vradenburg, co-founder Us Against Alzheimer’s, a patient advocacy group.

Vradenburg saw two parents on his wife’s side die of Alzheimer’s disease. Any success for aducanumab could encourage investment and further research, possibly triggering a cascade of new treatments, he said.

Carome understands despair; her mother died over ten years ago from Alzheimer’s disease after battling the disease for 10 years. Still, he fears the FDA could potentially approve a drug that doesn’t work.

“This could raise false hope for millions of patients and their families, ”he said. “This could have negative financial impacts and potentially bankrupt the Medicare program and ultimately delay and undermine future research into Alzheimer’s drugs that may be effective.”

The FDA’s handling of the situation echoes a 2016 episode where, despite objections from its own critics, the agency’s management approved a drug for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a deadly disease that primarily strikes young people. boys. Sarepta Therapeutics Inc. had only limited – and, to FDA advisers and reviewers, unconvincing – data on the drug’s effectiveness. But the drug, called Exondys 51, was backed by desperate parents whose sons were grieving.

Effect sparkles

At the time, FDA Examiner Ellis Unger warned the move could set a bad precedent. Future drug approvals could be based on “a simple flicker of effect,” he said, according to agency documents posted online.

Tom Williams / CQ-Roll Appeal Group

Dunn, who was then director of the neurology products division at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, told a group of agency advisers meeting in April 2016 that agency staff had “genuine concerns. About the data behind Exondys 51. But he and Unger were rejected by Janet Woodcock of the FDA, who has just been appointed acting commissioner by President Joe Biden.

Woodcock declined to comment. Sarepta did not respond when contacted for comment.

Now, the agency must determine how to overcome a potential deadlock on aducanumab. Massie and other critics of the drug have suggested that a landmark third trial before an FDA ruling would clear up the confusion. Advocates want access for patients now. They say Biogen may conduct a study after the drug hits the market to try to confirm the benefits of aducanumab.

Approving the drug risks sending a message that the FDA is ready to act on weak evidence, said Alexander, the Johns Hopkins-based FDA adviser.

“This is clearly a devastating disease for which new treatments are urgently needed,” he said. “For this reason, it is vital that the FDA and the market get there.”

Source link