[ad_1]

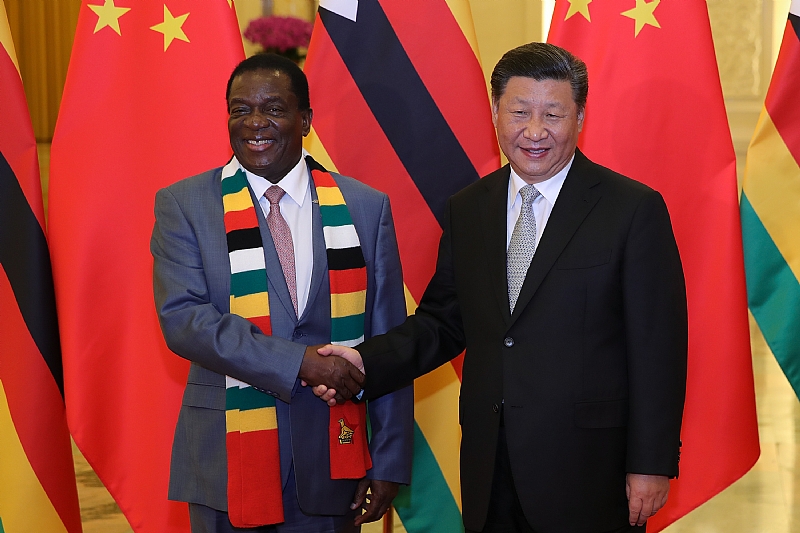

In November 2017, the Zimbabwean army replaced Robert Mugabe as head of state with his longtime confidant Emmerson Mnangagwa. He declared Zimbabwe “open for business”, linking foreign relations to economic policy. As he stated

We look forward to playing a positive and constructive role as a free, democratic, transparent and responsible member of the family of nations.

International expectations (more than those of the local population) looked forward to translating these promises into policy. This was despite the fact that Mugabe’s departure had been anything but democratic.

But there has been little to no change in Zimbabwe’s political trajectory. The deepening economic crisis combined with a brutal crackdown on domestic government opponents has led to disappointments.

On the foreign policy front, Mnangagwa did no better. In a recently published analysis, we examine the state of Zimbabwe’s foreign policy. We identify what went wrong in its efforts to reconcile with Western countries with the aim of securing the lifting of sanctions, and why its efforts to reconcile with China also did not go as planned.

We conclude that Mnangagwa’s hopes of reorienting Zimbabwe’s foreign policy have been dashed by his government’s own actions. Its repressive response to the mounting economic and political crisis has increased rather than lessened its isolation. The more the Mnangagwa government fails to engage democratically with its own citizens, the more it will nullify any prospect of re-engagement.

Relations with neighbors

Since the Mugabe era, the African Union and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) have tolerated the policies of the Zanu-PF regime.

The annual SADC summit in 2019 demanded an end to Western sanctions. But the continued repressive nature of the Mnangagwa regime does not facilitate this loyalty.

Tensions began to appear. In August 2020, South Africa dispatched official envoys to Harare to pressure the Mnangagwa government to exercise restraint in its actions against opposition figures. The envoys were not greeted warmly. Instead, they were subjected to a presidential harangue and denied the opportunity to meet with the opposition.

A subsequent mission of the ruling party in South Africa, the African National Congress (ANC), acting as a liberation movement, was also treated badly.

South Africa’s patience may be running out. But, for its part, the Southern African Development Community preferred to officially ignore the developments by remaining silent. But while “business as usual” translates into continued political loyalty, it does not translate into increased economic collaboration.

The west

Two decades ago, the United States and the European Union imposed sanctions on those linked to the government in response to human rights violations. The Mugabe regime responded by blaming the West for its economic problems. Mnangagwa denounced the sanctions as Western attempts to bring about “regime change”.

Unimpressed by the rhetoric, the United States extended restrictive measures against targeted individuals and businesses in August 2018. In March 2019, U.S. sanctions were renewed.

In contrast, the EU has shown a greater willingness to re-engage with Harare. In October 2019, the EU announced an aid package, bringing support during the year to € 67.5 million. Aid to Zimbabwe since 2014 stood at € 287 million in 2020. This made Zimbabwe the EU’s largest donor. To alleviate the woes of the COVID-19 pandemic, it added an additional € 14.2 million in humanitarian aid in 2020.

Mnangagwa, however, continued to blame the West for the sanctions he compared to cancer. Respond to criticisms declared by the EU

Zimbabwe is not where it is because of the so-called sanctions, but years of mismanagement of the economy and corruption.

Likewise, the American Ambassador rejected “all responsibility for the catastrophic state of the economy and the government’s abuses towards its own citizens.”

U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Jim Risch called on the 16 member states of the Southern African Development Community to

focus their energies on supporting democracy and not on kleptocratic regimes.

Looking east

Zimbabwe’s deteriorating relationship with the West has coincided with China’s growing interest in accessing African resources for its own rapidly expanding industries. Zimbabwe’s growing isolation provided a convenient entry point.

But China’s greater involvement was motivated less by solidarity than by self-interest. And it is of singular importance to throw a lifeline to the needy Zimbabwean regime, which has given it enormous clout in leading the collaboration. Failure to repair relations with the West and other global institutions leaves Zimbabwe without any other development and cooperation partner, thus vulnerable to manipulation by China.

A first honeymoon began at the turn of the century, after Zimbabwe isolated itself from the West thanks to its accelerated land reform of 2000 and increased repression of political opposition. But China has become increasingly concerned with Mugabe’s indigenization policy. With Chinese companies being the largest foreign direct investors, the announced application of Zimbabwe’s 51% stake in assets exceeding USD 500,000 as of April 2016 has caused embarrassment.

Mnangagwa’s rise to the presidency may have received China’s blessing as the best option available. Nevertheless, strains quickly appeared. When it became increasingly clear that Zimbabwe was unable to repay its debts, China forgave some of the debts in 2018.

What particularly troubled Beijing was that Harare’s inability to pay his debts was believed to be due to the embezzlement or misuse of Chinese funds by the government. Consequently, it was necessary to tighten controls. This resulted in the signing of a currency swap agreement in January 2020.

In mid-2019, the Chinese Embassy in Harare had already stressed that development relies mainly on the efforts of one country. She expressed hope that the Zimbabwean side would continue to create a more favorable environment for all foreign direct investment, including Chinese companies.

Evidence suggests that China’s patience with a struggling Zimbabwean “friend of all time” is thinner. New economic challenges following the COVID-19 pandemic may have shifted priorities in global supply chains. It also affects the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s vast global infrastructure project. This could reduce interest in what Zimbabwe has to offer in terms of natural resources.

No stability, no money, few friends?

Zimbabwe’s foreign policy remains locked into the parameters of the recent past: the search for regional solidarity, remote from the West and increasingly dependent on China.

Yet China has its own very clearly defined interests. These focus on the extraction of mining and agricultural resources for its own national economy. As a strategic and development partner, Zimbabwe is of minor interest.

Sino-Zimbabwean relations are at the service of an elite of the Zanu-PF government. They are accused of “asset stripping”. They exclude any control, the participation of civil society and lack transparency and accountability. The lack of visible benefits for ordinary Zimbabweans has engendered anti-Chinese sentiments.

Failure to reestablish friendly relations with the West, and its unsuccessful “looking east” policy, left Mnangagwa’s regime with few options. Russia has entered the arena, showing increased interest in extractive industries, the arms trade and political fraternization.

It hardly looks like an alternative to the current ties with China. Bed mates are more than less the same. And an old saying comes to mind: with friends like these, you don’t need enemies.

The authors do not work, consult, own stock, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have not disclosed any relevant affiliation beyond their academic appointment.

By Henning Melber, Extraordinary Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Pretoria and

Roger Southall, Professor of Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand![]()

Source link