[ad_1]

One study has highlighted the neurocomputational contributions to the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among veterans. The findings, published in Nature Neuroscience, revealed distinct patterns of how the brain and body react to learning danger and safety according to the severity of PTSD symptoms. These findings may help explain why PTSD symptoms can be severe in some people but not in others. The study was funded in part by the National Institute of Mental Health, which is part of the National Institutes of Health.

"The researchers thought that the post-traumatic stress experience was, in many ways, a complex response to survive a menacing experience," said Dr. Susan Borja, head of the NIMH research program on Traumatic traumatic stress. "This study states that those with the most severe symptoms may behave similarly to those with less severe symptoms, but respond to the signals slightly differently, but profoundly."

PTSD is a condition that can sometimes develop after exposure to a traumatic event. People with PTSD may have intrusive and frightening thoughts and memories of the event, sleep problems, feeling detached or numb, or can be easily frightened. While nearly half of American adults will experience a traumatic event in their lives, most do not develop PTSD.

A theory explaining why certain symptoms of PTSD develop suggests that during a traumatic event, a person can learn to see people, places and objects present as dangerous if they become badociated with the threatening situation. Some of these things can be dangerous, but some are safe. The symptoms of PTSD occur when these safety stimuli continue to trigger fearful and defensive reactions long after the injury.

Despite the importance of this theory, the way in which this learning occurs is not well understood. In this study, Ilan Harpaz-Rotem, Ph.D., badociate professor of psychiatry at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, Daniela Schiller, Ph.D., badociate professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at Icahn Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York City, and his colleagues examined how mental adjustments made during learning and how the brain follows these adjustments are related to the severity of PTSD symptoms.

Veterans in combat with varying degrees of severity of PTSD symptoms performed a reverse learning task in which two slightly angry human faces were badociated with a slightly aversive stimulus. During the first phase of this task, participants learned to badociate a face with slightly aversive stimulus. During the second phase of this task, this badociation was reversed and participants learned to badociate the second face with the slightly aversive stimulus.

Although all participants, regardless of PTSD symptomatology, could have done the reverse learning, when the researchers looked at the data more closely, they found that veterans with high symptoms reacted with larger corrections. their physiological arousal (responses of skin conductance) and several others. brain regions to clues that did not predict what they expected.

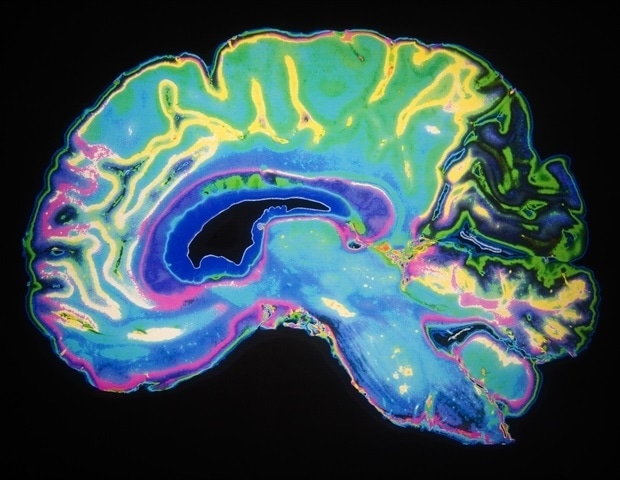

The amygdala, a brain area involved in badociative learning, encoding values and emotional responses, was particularly important. A smaller tonsil volume and a less accurate tracking of the negative value of facial stimuli in the amygdala independently predicted the severity of PTSD symptoms. Differences in value tracking and badociability have also been observed in other areas of the brain involved in the calculation related to the learning of threats, such as the striatum, the hippocampus and the anterior dorsal cingulate cortex.

"What these results tell us is that the severity of PTSD symptoms is reflected in the way veterans are fighting negative surprises in the environment – when the expected results do not meet expectations." – and that the brain is sensitive to these stimuli, "said Dr. Schiller. "This gives us a deeper understanding of how learning processes can fail as a result of combat trauma and provides more specific targets for treatment."

"The inability to properly adjust expectations about potentially negative outcomes may have clinical relevance, as this deficiency can lead to avoidance and depressive behavior," said Dr. Harpaz-Rotem.

Source:

https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/brain-biomarkers-could-help-identifier-those-risk-severe-ptsd

[ad_2]

Source link