[ad_1]

Antibiotic resistance, one of the greatest threats to the health of our time, has spread across the entire surface of the planet. And now, researchers have detected signs of it in one of the most remote areas of the planet.

In order to better understand what promotes the spread of antibiotic resistance, researchers turned to soil samples at Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago in the High Arctic near the North Pole.

Here, the team detected more than you expected from such a remote place – traces of 131 different antibiotic-resistant genes (ARGs) responsible for the spread of superbugs. These include the blaNDM-1 gene, detected for the first time in India, about 8000 kilometers from Svalbard.

Scientists believe that this particular gene has probably been carried by feces of migratory birds, other wildlife and even humans.

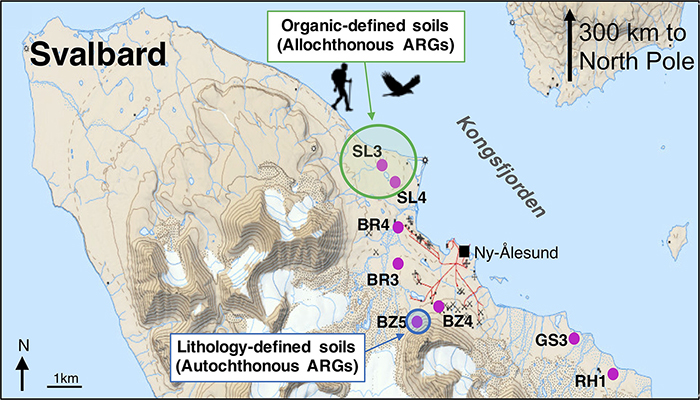

The team chose the Kongsfjorden area, Svalbard, as a study site because it is on an isolated island, devoid of agriculture and industry, and where it is so cold all year round that it is easy to preserve the DNA in the soil. In addition, less than 120 people live in this icy expanse of land.

BlaNDM-1's desire to move away from major hospitals and urban civilization is another sign that the fight against antibiotic resistance is a global, not a local, challenge.

(International Environment)

(International Environment)

"The polar regions are among the last suspected virgin ecosystems on Earth, providing a platform to characterize the background resistance of the pre-antibiotic period against which we could understand the rates of progression of RA pollution," states Dr. 39, a researcher, environmental engineer David Graham of Newcastle University. UK.

"But less than three years after the first detection of the blaNDM-1 gene in the surface waters of urban India, we find it thousands of miles away in an area where human impact is minimal . "

We know that by coding an enzyme called NDM-1, the blaNDM-1 gene can help develop resistance to multiple drugs in microorganisms – even "last resort" drugs such as carbapenems, that we try when all else fails.

And as bacteria evolve to fight the best treatments we can give them – from ordinary microbes to superb microbes – some estimates are already costing thousands of lives each year.

This situation will only worsen unless we can find ways to make our antibiotics more effective or develop new ones.

"Thanks to overconsumption of antibiotics, fecal releases and contamination of drinking water, we have accelerated the rate of evolution of superbugs," Graham said.

"For example, when a new drug is developed, natural bacteria can quickly adapt and become resistant, so very few new drugs are being prepared because their manufacture simply is not cost-effective. "

Although there is no immediate threat to health in the region, the overuse of antibiotics in a clinical setting may have led to the arrival of blaNDM-1 in one area as distant, which is why scientists are exploring other possibilities.

DNA was extracted from forty different samples of soil cores taken from the Kongsfjorden area in 2013. The 131 resistance genes detected covered nine different clbades of antibiotics, with blaNDM-1 being present in 60% carrots.

Researchers describe soil as both the "source and sink" of antibiotic resistance and hope to use Arctic soils as a baseline for measuring resistance and its spread, which will be difficult with microbial movements caused by l & # 39; man.

There is still hope to find and sample more virgin soil without ARG in these areas. By doing this, scientists seek to better understand how antibiotic resistance develops and develops, and from there, to find better ways to stop it.

For this to happen, the team suggests, we need to look closely at waste management, water quality and other human impacts on the environment to keep the Arctic environment as clean as possible.

"Encroachment in areas such as the Arctic is increasing the speed and scope of the spread of antibiotic resistance, confirming that solutions to AR should be viewed holistically rather than locally," he said. said Graham.

The search was published in International environment.

Source link