[ad_1]

The decision of the German Federal Cartel Office to order Facebook to change the way it processes users' personal data this week is a sign that the antitrust wave may finally backfire against the power of the platforms.

A European commission The source we spoke to, who commented on a personal basis, described this activity as "clearly pioneering" and "a big problem", even without Facebook being fined a dime.

The decision of the FCO forbids the social network on the contrary to link the data of the users on different platforms that it owns, unless to obtain the consent of the people (it can not not use its services without its consent). Facebook It is also forbidden to collect and link user data from third-party websites, for example via its tracking pixels and social plugins.

The order has not yet entered into force and Facebook is attractive, but if it were to come into effect, the faces of social networks would be de facto reduced because of the silo setting of their platforms at level of data.

To comply with the order, Facebook should ask users to freely consent to a data exploitation, which the company does not do at the moment.

Yes, Facebook could still manipulate the desired result by users, but this would make it more difficult to challenge under EU data protection law, as its current approach to consent is already in question.

The updated EU Privacy Framework, the RPGD, requires that consent be specific, informed and freely consented. This standard supports challenges related to Facebook's "price" of entry (still fixed) to its social services. To play, you must always agree to transmit your personal data so that your attention can be brought to the attention of advertisers. But lawyers say that this is neither the protection of privacy nor the protection by default.

The only "alternative" offer on Facebook is to tell users that they can delete their account. Anyway, that would not stop the company from following you in the rest of the mainstream web. Since Facebook's monitoring infrastructure is also integrated throughout the Internet, it also helps profiling non-users.

European data protection regulators are still investigating a very large number of GDPR complaints related to consent.

But the German FCO, who said he had established contacts with the privacy authorities during his Facebook data collection survey, called this type of behavior "exploitative", also considering that the social service held a monopoly on the German market.

There are therefore two types of legal attacks: competition law and privacy law, which threaten the surveillance-based business model of Facebook (and other adtech companies) in Europe.

A year ago, the German competition authority also announced the opening of an online advertising industry survey to address concerns about the lack of market transparency. His work here is far from over.

Data limitations

The lack of a big, flagrant fine linked to the German FCO's decision against Facebook means that this week's story is less of a headline than the European Commission's recent antitrust fines against Google. – as the record fine of $ 5 billion inflicted last summer for anticompetitive behavior related to the Android mobile platform.

But we can argue that the decision is just like, if not moreSignificant, because of the structural remedies ordered on Facebook. These solutions have been equated with an internal break in society – with forced internal separation of its multiple platform products at the data level.

This obviously goes against the preferred trajectory of the giants of the platform, which has long been to tear down the walls of modesty; consolidate user data from multiple internal (and even external) sources, disregarding the notion of informed consent; and mine everything that is personal (and sensitive) to create identity-related profiles to form algorithms that predict (and, in some cases, manipulate) individual behavior.

If you can predict what a person will do, you can choose the advertisement to broadcast to increase the chances of clicking. (Or, as Mark Zuckerberg says, "Senator, we're showing ads.")

This means that a regulatory intervention that impedes the ability of an advertising technology giant to pool and process personal data begins to be really interesting. Because a Facebook who can not join data points from his sprawling social empire – or even the mainstream web – would not be such a huge giant in terms of data lighting. And neither, therefore, surveillance surveillance.

Each of its platforms would be forced to be a more discreet (and even discreet) type of business.

The competition against siled data platforms with a common owner – instead of a mega-surveillance-interconnected network – is also starting to seem almost possible. He suggests a playground that resets, if not fully leveled.

(Whereas, in the case of Android, the European Commission has not ordered specific remedies – allowing Google to create "patches" itself; and thus to fashion the most interesting "patch" of its own.)

In the meantime, just look where Facebook is now seeking to go: a technical unification of the backend of its various social products.

Such a merger would collapse even more completely nested walls and platforms that began to be completely separate products before being replicated into Facebook's empire (not to mention, through surveillance-based acquisitions).

Facebook's plan to unify its products on a single back-end platform is very much like an attempt to remove technical barriers to antitrust hammers. It is at least harder to imagine breaking a business if its multiple, separate products are merged into a single server, which makes it possible to cross and combine data streams.

Faced with Facebook's sudden desire to technically unify its dominant social networks (Facebook Messenger; Instagram; WhatsApp) is a growing drum beat of calls for scrutiny of the giants of competition-based technology.

This has been building for years, as the market power – and even the democratization potential of democracy – of the giants of supervisory oversight of capitalism has been observed.

Calls to break the giants of technology no longer have any suggestive meaning. Regulators are regularly asked if it is time to do so. As head of competition at the European Commission, Margrethe Vestager, That's when she made Google's last mbadive anti-trust fine last summer.

She then replied that she did not know if breaking up with Google was the right solution – preferring to try out solutions allowing competitors to try their luck, while stressing the importance of legislating to ensure 'transparency and transparency'. Equity in business-to-business relations ". "

But it's interesting to note that the idea of breaking the tech giants is now playing such a good role in political theater, suggesting that consumer technology companies with resounding success – who have long relied on brilliant marketing claims based on convenience, saccharine was the focus. "Free services – have lost much of their populist appeal, stubborn by so many scandals.

From terrorist content to hate speech to electoral interference, exploitation of children, intimidation, abuse. There is also the question of how they organize their tax affairs.

Public opinion about the technology giants has matured with taking into account the "costs" of their "free" services. Newcomers have also become the institution. People do not see a new generation of "hug capitalists", but another group of multinationals; Very sophisticated but distant machines that earn much more than they bring back to the societies they feed on.

Google's hint of naming each Android iteration after a sweet treat is an interesting parallel to the perceptions (also changing) of the public about sugar, with a heightened focus on health issues. What's his sickly gentleness mask? And after the sugar tax, we now have politicians who ask for a tax on social networks.

This week again, the deputy head of the main opposition party in the United Kingdom called for the establishment of autonomous regulation on the Internet, with the power to dismantle technological monopolies.

Talking about breaking well-oiled machinery and concentrating wealth is considered a winner of the populist vote. And the companies that political leaders flattered and looked for public relations opportunities are treated as political punches. Called to attend delicate grilling by transplant committees, or taken to a vicious task verbally to the most prominent public podia. (Although some undemocratic heads of state still insist on putting pressure on the tech giant.)

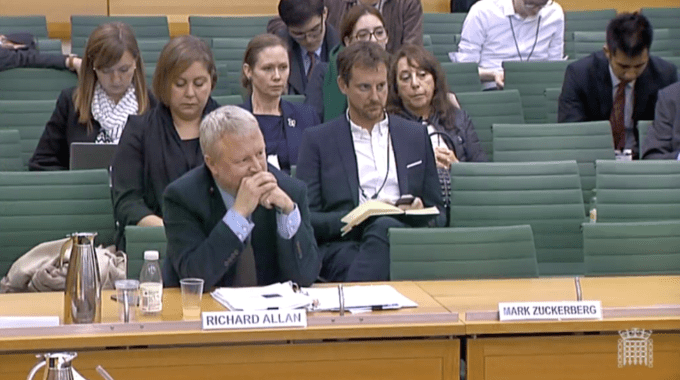

In Europe last year, Facebook was reluctant to ask the British parliament to ask Zuckerberg to address the issues of policymakers certainly did not go unnoticed.

Zuckerberg's empty presidency of the DCMS committee has become both a symbol of the company's failure to accept broader societal responsibility for its products and a sign of market failure. the CEO so powerful that he does not feel responsible to anyone; neither its most vulnerable users nor their elected representatives. Thus, British politicians on both sides of the aisle are a political capital talking about cutting the giants of technology.

The political fallout from the Cambridge Analytica scandal seems far from over.

The way a UK regulator could successfully tip a regulatory hammer to dismantle a global Internet giant like Facebook, headquartered in the US, is another matter. But decision makers have already crossed the rubicon of public opinion and want to talk.

This represents a radical change from the neo-liberal consensus that allowed competition regulators to sit idle for more than a decade, as new technologies covertly traded data between people and their rivals, and basically turned into distortions. of the market. giants with Internet-wide data networks to hook users and buy or block competing ideas.

The political spirit seems to want to go, and now the mechanism to break the attitude that distorts the platforms on the markets is perhaps taking shape.

The traditional antitrust remedy of breaking a business in its business sectors still seems difficult to handle in the face of the fast pace of digital technology. The problem is to provide such a patch quickly enough that the company has not already reconfigured to route the reset.

The Commission's antitrust decisions on technology have taken precedence over Vestager. Still, there is always the impression of watching paper users wander through the molbades to try and catch a sprinter. (And Europe did not go as far as trying to impose a platform break.)

But the decision of the German FCO against Facebook suggests another solution to regulate the dominance of digital monopolies: structural solutions focused on the control of access to data that can be configured and applied relatively quickly.

Vestager, whose mandate as head of competition in the European Commission will soon come to an end (although other roles remain to be filled by the Commission)contention), has defended this idea.

In an interview on BBC Radio 4 Today & # 39; hui In December, during her program, she threw cold water on the issue of breaking the tech giants, saying that the Commission could instead look at how large companies have access to data and resources to limit their power. Which is exactly what the German FCO did in his order to Facebook.

At the same time, the updated framework for data protection in Europe has drawn the greatest attention to the extent of the pecuniary penalties that can be imposed for major compliance offenses. But the regulation also gives data observers the power to limit or prohibit treatment. And this power could also be used to reshape an economic model eroding rights or totally deprive such companies.

#GDPR allows for a permanent ban on data processing. It is the nuclear option. Much more severe than any fine you can imagine, in most cases. https://t.co/X772NvU51S

– Lukasz Olejnik (@lukOlejnik) January 28, 2019

The merging of privacy and antitrust concerns only reflects the complexity of the challenge regulators are currently facing in trying to contain digital monopolies. But they are getting ready to take up this challenge.

In an interview with TechCrunch last autumn, Giovanni Buttarelli, head of data protection in Europe, told us that the Union's privacy regulators are more oriented towards collaboration. with the antitrust agencies to respond to the power of the platforms. "Europe would like to speak with one voice, not only in the field of data protection, but also by better addressing this issue of the digital dividend, monopolies – not by sectors," he said. -he declares. "But first, joint application and better cooperation are essential."

The decision of the German FCO represents tangible proof of the type of regulatory cooperation that could finally repress the giants of technology.

Mr Buttarelli said: "It is not necessary for competition authorities to apply other areas of law; they simply need to identify where the most powerful companies set the wrong example and harm the interests of consumers. Data protection authorities are able to badist in this badessment. "

He also had his own prediction for surveillance technologists, warning: "This case is the tip of the iceberg – all digital information ecosystem businesses that rely on tracking, profiling and targeting should be prevented."

So maybe, finally, the regulators have understood how to go fast and break things.

[ad_2]

Source link