[ad_1]

Since the beginning of the year, the US government and private security firms have warned of a wave of sophisticated attacks that divert domains belonging to several governments and private companies on an unprecedented scale. On Monday, a detailed report provided new details that helped explain how and why the many DNS hijackings allowed attackers to siphon a considerable number of emails and other login credentials.

The article, published by KrebsOnSecurity reporter Brian Krebs, said that over the past few months, the attackers responsible for the so-called DNSpionage campaign have compromised key components of the DNS infrastructure of more than 50 companies and government agencies from the Middle East. In its Monday article, the attackers, suspected of being based in Iran, have also taken control of areas belonging to two very influential Western services: the Netnod Internet Exchange in Sweden and the Packet Clearing House in northern California. With domain control, hackers were able to generate valid TLS certificates allowing them to launch attacks intercepting the interception of sensitive identification data and other data.

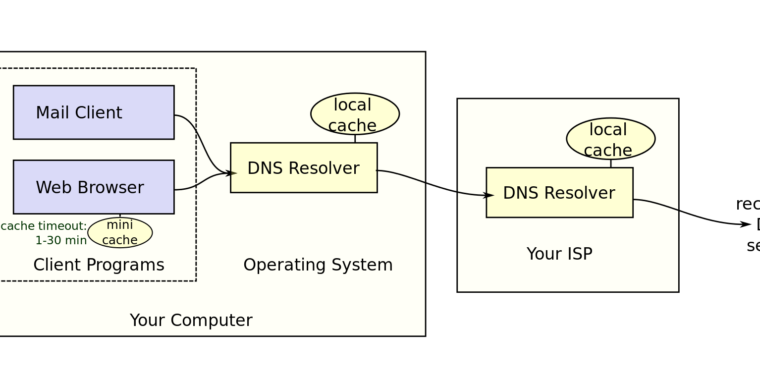

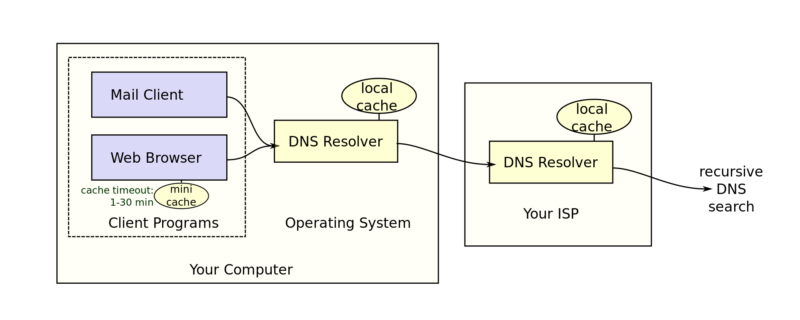

For DNS, the DNS is one of the most fundamental services of the Internet by translating human-readable domain names into the IP addresses that a computer needs to locate other computers on the global network. DNS hacking involves falsifying DNS records to point a domain to an IP address controlled by an attacker rather than the legitimate owner of the domain. DNSpionage has pushed DNS piracy to new heights, largely compromising the key services companies and governments rely on to provide domain searches for their sites and email servers.

Target key players

As the operator of one of the 13 root name servers essential to the operation of the Internet, Netnod is certainly considered a key pillar on which DNSpionage could support its mbad piracy frenzy. In late December and early January, elements of the Swedish service's DNS infrastructure, in particular sa1.dnsnode.net and sth.dnsnode.net, were hacked after hackers gained access to accounts on Netnod's domain name registration desk, said Krebs, who cited interviews with the company and a statement released Feb. 5.

"As a participant in international security cooperation, Netnod learned on January 2, 2019 that we were caught up in this wave and that we had suffered a MITM (middle man) attack," officials said. Netnod in the newspaper. declaration. "Netnod was not the ultimate goal of the attack. The goal is supposed to have been the capture of login information for Internet services in countries other than Sweden. "

Krebs then said that the DNS infrastructure owned by Packet Clearing House was also compromised when the attackers hijacked pch.net after gaining unauthorized access to the domain's registrar. In fact, the falsified recordings of pch.net and dnsnode.net referred to the same sources: Key-Systems GmbH, a domain registrar in Germany and Frobbit.se, a Swedish company.

Packet Clearing House also plays a key role in the functioning of the Internet as the non-profit entity manages significant amounts of the global DNS infrastructure. Part of this infrastructure includes the formal research of more than 500 top-level domains, including many areas in the Middle East targeted by DNSpionage.

PCH Executive Director Bill Woodbad told Krebs that DNSpionage attackers were able to modify many domain name registrations for targeted Middle Eastern TLDs after the phishing IDs used by Key-Systems to bring domain changes to their customers. Krebs wrote:

Specifically, he said, hackers have phishing the credentials that the PCH registry office was using to send signaling messages known as the Extensible Provisioning Protocol (EPP) ). EPP is a little-known interface that serves as a back-end type to the global DNS system, allowing domain registrars to notify regional registries (such as Verisign) of changes to domain registrations, including new ones. domain registrations, changes and transfers.

"In early January, Key-Systems claimed to believe that its EPP interface had been misused by a person who had stolen valid identifiers," Woodbad said.

Key-Systems declined to comment on this story, beyond saying that she does not discuss details of her reseller client's business.

Netnod's written statement on the attack returned the inquiries to the company's director of security. Patrik Fältströmwho is also a co-owner of Frobbit.se.

In an email to KrebsOnSecurity, Fältström announced that unauthorized EPP instructions were sent to various registries by the DNSpionage attackers from Frobbit and Key Systems.

"From my point of view, the attack was clearly the first version of a serious attack by the EPP," he wrote. "That is, the goal was to get the right EPP orders sent to the registries. Personally, I am extremely worried about extrapolations to the future. Should registries allow any EPP order from the registrars? We will still have weak registrars, right?

The imperfect world of DNSSEC

The misuse of badets described in Monday's report highlights the effectiveness and disadvantages of DNSSEC, a protection designed to counter DNS diversion by requiring DNS records to be digitally signed. If a record has been changed by a person without access to the private DNSSEC signing key and, therefore, the record does not match the information published by the owner of the zone and served on an authoritative DNS server, a name server will block the end. the user to connect to the fraudulent address.

Two of the three attacks on Netnod were successful because the servers involved were not protected by DNSSEC, reported Krebs. A third attack, which targets Netnod's internal messaging network infrastructure and is protected by DNSSEC, highlights the limitations of backup. Because attackers already have access to Netnod's registrar systems, hackers have been able to disable DNSSEC long enough to generate valid TLS certificates for two of Netnod's mail servers.

Then something unexpected happened. Quoting Netnod's CEO, Lars Michael Jogbäck, Krebs wrote:

Jogbäck told KrebsOnSecurity that once the attackers had obtained these certificates, they reactivated DNSSEC for the company's targeted servers while apparently preparing to launch the second stage of the attack, diverting the traffic pbading through its servers. messaging to machines controlled by attackers. But Jogbäck said that for some reason, the attackers had neglected to use their unauthorized access to his registrar to disable DNSSEC before attempting to siphon Internet traffic later.

"Fortunately for us, they forgot to remove it when they launched their man-type attack in the middle," he said. "If they had been more competent, they would have removed DNSSEC on the domain, which they could have done."

DNSSEC performed better for Packet Clearing House, but there were still gaps:

Woodbad indicates that PCH validates DNSSEC across its entire infrastructure, but that all of the company's customers – particularly some of the Middle East countries targeted by DNSpionage – had not configured their systems to fully implement the technology. .

Woodbad stated that the PCH infrastructure was targeted by DNSpionage attackers during four separate attacks between December 13, 2018 and January 2, 2019. At each attack, hackers turned on their word search tools. pbad for about an hour, then extinguish them before returning. the network at its original state after each execution.

Attackers did not need to turn on their watch for more than an hour each time, because most modern smartphones are set to continuously retrieve new messages for any accounts the user may have configured on their device . Thus, the attackers were able to retrieve a lot of identification information at each brief hijacking.

On January 2, 2019, the same day that DNSpionage hackers attacked Netnod's internal messaging system, they also targeted PCH directly, obtaining Comodo SSL certificates for two PCH domains that manage the company's internal email.

Woodbad stated that PCH relied on DNSSEC to completely block this attack, but that it managed to obtain the email credentials of two employees who were traveling at the time. The mobile devices of these employees downloaded their corporate email via the hotel wireless networks which, as a prerequisite for using the wireless service, required their devices to use the hotel's DNS servers, and not the DNSSEC compatible systems of PCH.

With DNSSEC minimizing the effects of hijacking the Packet Clearing House mail server, DNSpionage attackers, Krebs reported, have opted for a new tactic. At the end of last month, Packet Clearing House sent customers a letter informing them that a server containing a database of users had been compromised. The database stores user names, pbadwords protected by the hash function bcrypt, e-mails, addresses and organization names. The leaders of the Packet Clearing House said that they had no evidence that the attackers had accessed the database of users or exfiltrated it, but they provided the information by concern for transparency and precaution.

Monday's report still leaves some key questions about unanswered DNSpionage. According to an emergency directive issued last month by the Department of Homeland Security, "several areas of executive agencies" have been affected by the misappropriation campaign. Until now, there is little public information about the agencies involved or possibly stolen data.

The report, however, is the last reminder of the importance of locking down the DNS infrastructure to prevent such attacks. Locking measures include:

- Using DNSSEC for both signature fields and validating responses

- Use Registry Lock or similar services to prevent domain name registrations from being changed

- Using Access Control Lists for Applications, Internet Traffic, and Monitoring

- Use multi-factor authentication that must be used by all users, including subcontractors

- Use strong pbadwords, with the help of pbadword managers if needed

- Regularly review your accounts with registrars and other suppliers and look for signs of compromise.

- Monitoring the issuance of unauthorized TLS certificates for domains

Krebs' post here contains many more details.

Source link