[ad_1]

March 26, 2019 – For many consumers, palm oil has become synonymous with the devastation of the environment in Southeast Asia. The industry has resulted in mbadive deforestation in the region, a reduction in orangutan habitat and compromised local livelihoods. Indonesia has become the third largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a partnership between stakeholders in the palm oil sector, such as producers, retailers and NGOs, was created more than 10 years ago to make the industry more environmentally and socially responsible. It helped, but critics argue L & # 39; industry is still far from sustainable.

Meanwhile, the palm oil industry has developed in other parts of the world. Latin America, for example, saw an increase in palm production. And over the past decade or so, large-scale palm oil production has spread to West and Central Africa. Although some people have welcomed this situation in the hope that this would create economic opportunities, a number of communities are trying to resist either the presence of the industry itself or the way in which individual companies operate in their countries. How these efforts will unfold could determine whether the industry can find a way to be more sustainable in Africa, as well as the fate of communities across the continent, besides non-human primates.

"Palm oil companies will not replace [people in affected communities]but their culture, their history, their value, their traditional institutions will be completely changed, "said Alfred Brownell, founder of the Liberian Lawyers Network. Green advocates and currently a distinguished research fellow in residence at Boston's Northeastern University School of Law. He lives in the United States in exile out of fear for his life, after he says that he was threatened by private security guards who protect sacred lands to free up space for palm oil development in Liberia. But he represented the indigenous communities of Sinoe County in Liberia, where residents say only since the Golden Veroleum Liberia palm oil company (GVL) arrived in 2010crops were destroyed, sanctuaries were desecrated, cemeteries and graves were denigrated, rivers were diverted or barred, and valuable wetlands were polluted.

"It was fertile ground for growing vegetables and other staple foods, in addition to our local food basket," Brownell wrote in a letter to the RSPO on behalf of the locals. "All are no more. All wetlands in our communities have been filled to make way for palm oil. "

Unlike Indonesia and Latin America, oil palm is native to West Africa and is an important traditional crop with varied uses. Here, a woman pours transformed palm oil into a glbad bottle in the village of Masethele, Bombali district, Sierra Leone.

Photo courtesy of Aubrey Wade | Namati

Liberia is home to the largest remaining extent of the Upper West African Forest of West Africa, which possesses some of the richest biodiversity in the world. In addition to the wetlands and agricultural lands on which communities depend, the forest is threatened by the expansion of palm oil production, among other commercial activities. If she disappears, says Brownell, the same goes for the spiritual connection that many Aboriginal communities have with her. "That's why we looked at this complaint before the roundtable," he says.

Growing demand, growing industry

Palm oil production continues to grow steadily worldwide. "Production has doubled in the world every 10 years over the last 40 years," said Thomas Mielke, CEO of the company's Oil World market badysis company. "Palm oil has become the most important vegetable oil in the world."

This is because it is cheap and has more and more uses. It's in all kinds of packaged foodfrom instant noodle crackers to ice cream, and the rapid growth in global consumption of processed foods is one of the main reasons for the explosion in demand. It is also used in soaps, cosmetics, biodiesel and replacement of mineral oil. And since it is a very productive crop, the impacts on land use could be even greater if the world tries to replace the palm with a different vegetable oil.

In Africa, about 3 million hectares of land "traditionally used or inhabited by local communities", covering both forests and farmland, have been acquired by palm oil producing companies, according to Devlin Kuyek, researcher at GRAIN, a non-profit organization that supports small farmers. This corresponds to the reports of the Economist in 2014, when the magazine reported, "Over the past decade, politicians in West Africa and Congo Basin countries have leased about 1.8 million hectares [4.5 million acres] land for palm oil plantations, according to Hardman, a research company based in London. 1.4 million additional hectares [3.5 million acres] is being sought. Foreign companies to watch for include Wilmar, Olam, Sime Darby, Golden Veroleum and Equatorial Palm Oil. At the same time, citing statistics from the Proforest non-profit organization, The Guardian reported in 2016 that "[a]s as much as 22 million hectares (54 million acres) of land in West and Central Africa could be converted to palm plantations over the next five years. "

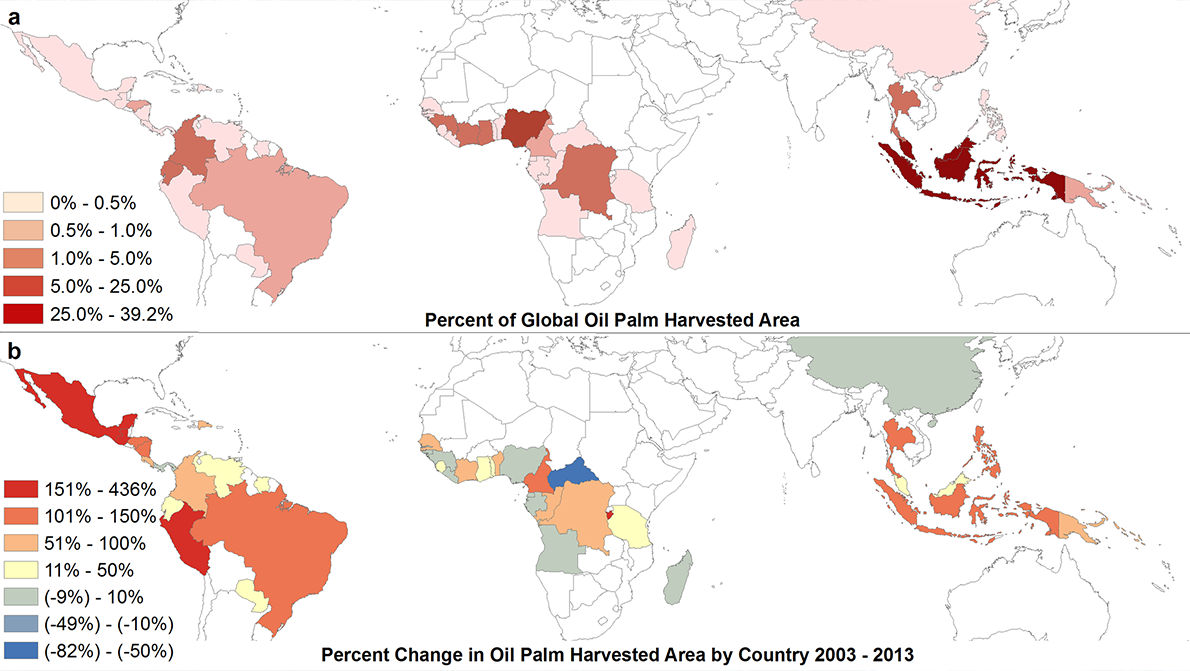

World production of palm oil. a) Percentage of total area harvested from oil palm in the world as reported by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in 2013. b) Percentage change in area harvested from oil palms reported by FAO by country, 2003-2013. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159668.g001. Source: Vijay, V., Pimm, S.L., Jenkins, C.N. and Smith, S.J. (2016). Oil palm impacts on recent deforestation and loss of biodiversity. PloS One, 11 (7), e0159668. Click on the image to enlarge.

Although it is difficult to predict the exact number of future large-scale expansion, the industry is undoubtedly growing. "Despite the limited surface area currently planted, some Latin American and African countries have grown faster than [2003–13] whether it is Indonesia or Malaysia, " the researchers wrote in PLOS One in 2016. "If these growth rates are maintained, the expansion of oil palm plantations in these countries will likely have increased impacts."

From Liberia to the Democratic Republic of Congo, a battle has emerged in recent years to find out where and how to develop palm oil. Impacts on local water resources, wildlife populations, biodiversity and climate change are of concern. But the heart of the problem, which drives communities to express themselves en mbade, is the control of the land. To increase their production of palm oil, a number of companies have relied on what critics describe as land grabbing.

Communities do not oppose oil palm cultivation. Unlike Indonesia and Latin America, the oil palm is native to West Africa and is an important traditional crop with a variety of uses. But in the past, it had become wild or integrated into fields with other cultures. The big world producers depend on monocultures.

The RSPO was established in 2004 to create environmental and social standards for the palm oil sector. A number of environmentalists and human rights groups have criticized as ineffective or not effective enough. A study who evaluated a set of sustainability parameters on oil palm plantations in Indonesia, found no difference between RSPO certified plantations and those that are not. Another noted that certification was sometimes badociated with lower rates of deforestation, but many plantations were located in areas where much of the forest had already been destroyed.

In Cameroon, the oil palm plantation is evident when various trees move to monoculture. Photo courtesy of Mokhamad Edliadi | CIFOR

Brands that use palm oil, meanwhile, use certification to badure their customers that the ingredient is sustainable. "They talk a lot, but they base all their purchases on RSPO certification," said David Pred, executive director of Inclusive Development International, a nonprofit human rights organization. He adds, however, that all the negative attention paid to the RSPO has led to some improvements. "The mechanism now has some teeth, which I did not think I was a few years ago. But it's certainly not a panacea. There are still many loopholes, and I think that gives a veneer of credibility. "

In Africa, the certification itself supposed to ensure sustainability is actually responsible for the loss of more land than will be used for production by communities, according to Kuyek. The RSPO, he says, is encouraging companies to include more land in their contracts than they will convert plantations, so they can say they reserve a certain amount for protection purposes. . "In a sinister way, it actually encourages more land grabbing," he says. When asked if he saw the law on land protection as valid in the sense of ecological conservation, Kuyek wrote in an e-mail: "I'm afraid I will not do it. There can be no meaningful program for integrated ecological conservation in a fundamentally destructive model of plantation agriculture. "

John Buchanan, vice president of sustainable production at Conservation International, a nonprofit member of the RSPO for more than a decade, has heard similar concerns. For him, this shows the crux of the much larger and seemingly insoluble problem of poverty. "I've heard about this general concern, but not the communities where we work [in Liberia], "he says." What communities have most important to say is, "When can we get our palm oil and how fast?" I think they're really looking forward to see what they perceive as development opportunities that go with it. "

Elizabeth Clarke, Global Head of Palm Oil for WWF, wrote in an e-mail, "If properly implemented, the recently revised RSPO standard should contribute to the protection against the grabbing of lands because she [High Conservation Value] and HCS [High Carbon Stock] badessments, FPIC and consultation with communities and all other relevant stakeholders, prior to any new planting. "

Kuyek reports a RSPO-certified plantation in Gabon, where 72,000 hectares out of 144,000 (178,000 out of 356 acres) are intended for the protection of valuable forests and other areas.

Last year, Lee White, conservation biologist at the Parks Agency of Gabon, told National Geographic"What we are trying to do in Gabon is to find a new development path in which we do not cut our entire forest, but maintain a balance between oil palm, agriculture and forest preservation."

In an e-mail, Dan Strechay, US representative of the RSPO, acknowledged that "there had been land grabbing and conflict with communities," but said that by November 2018, the roundtable had revised its set of standards known as Principles and criteria (P & C) who "goes further by ensuring that communities have access to independent consulting resources and better documentation of FPIC procedures during the process." … To deal with potential land rights issues, P & C requires documentation of legal ownership or lease, or the authorized use of customary land. In the new P & C, this may include documents other than the legal title establishing a land use right. For communities without formal legal recognition of their land, but who have resided there for generations, this will contribute to better protection of their land rights. "

There is no simple answer and Buchanan stresses the importance of looking at the bigger picture and looking for ways to respond to the many different and conflicting interests and needs. "How can we strike that balance between conservation and their economic needs?" He said. "Our experience in Liberia shows us that strict sustainability standards do not necessarily safeguard forests and do not benefit local communities. If these communities can not find a way to meet their aspirations and lead a better life, if they can not get palm oil, they will look for something else. "

Daniel Krakue of Social Entrepreneurs for Liberty Development, a non-profit organization based in Liberia, says the Liberian city of Plusunnie was probably the most affected by the palm oil company GVL. He says the water is polluted, that land that has always been treated and grown as a communal resource – as is common in Liberia – has been lost to palm trees and that areas where people would hunt and trap had disappeared. "They converted all the land for planting purposes," he says. "Some of these young and dynamic families see this as a development. But when they get fired, they have to go back to town, and the city is no longer habitable. "

But as much of the contracted land in Africa has not yet been planted, it is still possible to advance on a different path for much of what could be the next world center of palm oil. And the reaction of the community has been swift in many areas.

GVL, who left the RSPO in 2018, has not responded to requests for comments, but Golden Agri-Resources (GAR), the largest investor in GVL and the world's second largest palm oil company, says GVL is subject to social and environmental policy. In a statement sent in response to questions, the company stated, "While some communities complain, GAR understands that in most areas where GVL is active, FPIC has been implemented in accordance with RSPO guidelines and communities. welcome the presence of GVL. Nevertheless, GVL has recognized the need to continually improve its sustainability processes and has begun to implement a sustainability action plan, such as ad by its general manager on July 20, 2018. GAR is committed to supporting GVL in this field and sent a technical team to Liberia in September 2018 to badist. RBM continues to provide support as needed and will regularly badess GVL's compliance with GSEP. [GAR’s Social and Environmental Policy]. The GVL case has been included in the list of GAR grievances, which is Publicly available and GAR actively monitors and monitors GVL's progress. "

Krakue says that the RSPO is doing more good than not at all. "Things would be much worse [without RSPO]. Even though the way they handled the complaints from Liberia was unsatisfactory, "he says," at least the RSPO serves as a control and balance system for these companies. " But he and other lawyers think there is still a lot to do.

In Sierra Leone, Namati, a nonprofit organization that works with local legal advocates around the world to help communities enforce the laws designed to protect them, helped a community win an award. decision of the Court in November, the company ordered Siva Group, a Singapore-based palm oil company, to return land to the community and pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in unpaid rent. In the Makpeele chiefdom in the Pujehun district of southern Sierra Leone, Namati represented the landowners who had lost large amounts of land in a lease of which they had only been informed after their signature by a Acting Chief of the region. They negotiated a new lease that reduced the amount of land involved from more than 30,000 hectares (2,300 hectares) to 2,300 hectares (5,700 acres) and put in place a "marginal culture" model. The specifics of this model vary from one site to another, but the company generally exploits some land as a plantation and also provides smaller plots on which local farmers can grow palm independently. In other words, it allows contract farming rather than relying on a single company to provide all the job opportunities.

A Sierra Leonean farmer is preparing to climb on one of his palm trees to harvest the kernels, which will be processed into palm oil. Photo courtesy of Aubrey Wade | Namati

A number of community advocates believe that this type of outsourced farming system, even if it is not perfect, could offer a way for the development of palm oil that is less destructive to the environment than in Asia and more inclusive of local communities that can benefit from it. development rather than being moved by it.

Eleanor Thompson, a Namati lawyer involved in the Pujehun District case, said the outsourcing model "is arguably the best lease of the country's agri-food industry with respect to the benefits. for the inhabitants and the standards of environmental protection. "

Sonkita Conteh, country director for Namati, says Sonkita Conteh, country director of Namati, explains that "large-scale operations provide" only two or three months of work per year. If you have transferred all your land to the company, you can not deprive yourself of it. With the subcontracting culture model, "you always get the production that companies need and, at the same time, you also help farmers." They have jobs all year round and small operations do not have the same impact on the water supply. or use chemicals as intensively as large plantations, says Conteh.

Sierra Leone has had a law in 2016, companies investing in agriculture must create outsourcing opportunities for small farmers. In Liberia, Krakue said discussions were also underway between companies and farmers to establish subcontracts.

Ryan Zinn, manager of regeneration projects at Dr. Bronner's, a for-profit company that manufactures soap and other personal care products, is a little more skeptical about the model subcontracting, claiming that farmers can only really benefit from it if there is no monopoly. the local market. Otherwise, in the event of disagreement over price or quality, for example, farmers may end up without a buyer.

"From a small farmer's point of view, I think it only works if there is enough competition in the region," he says. "If there is only one mill in the area, it can become quite risky."

For Brownell, these are the brands that buy palm oil for their products. Palm oil producers are not vulnerable to consumer pressure that can be exerted on more well-known brands through actions such as boycotts.

RSPO's Strechay says in his e-mail that "growing production in Africa, FPIC and the inclusion of smallholder farmers are important factors to consider in the region's sustainability debate. For sustainable palm oil to become the norm, solutions must be accessible at all levels and at all levels of supply. He added: "Smallholders depend on oil palm cultivation for their livelihood, but suffer from lower yields and limited access to the market. This problem can be solved by helping smallholders move to sustainable production and remains a top priority for the RSPO. This has led to the development of a separate additional standard, applicable exclusively to small independent operators: the standard for smallholder RSPOs. "

In Ghana, about 600 farmers produce palm oil that they sell directly to Mr. Bronner's. They grow up on their own land or on land they rent, for example, from a neighbor – and not from land that is controlled by the company – and can sell to any buyer to whom they have access, although Mr. Bronner's pay premiums for fair trade and organic production. . Zinn says that society is is now working with farmers to add a more diversified, agroforestry-based approach to palm oil cultivation. A more diversified system, he says, is more resilient to climate change and also offers more stability to the local economy.

But it's also more expensive. Zinn estimates that the purchase price by Dr. Bronner's in this way is 10 to 20% higher than the basic price of palm oil in the world market. It's a choice that Dr. Bronner's made, and although he thinks the model could be adapted, it can only happen if the market demands higher value oil. "Your production costs will increase, as long as the consumer is willing to pay for it, this model can absolutely be reproduced," he says. "The question is whether there is a political or economic will to make it happen."

For Brownell, these are the brands that buy palm oil for their products. Palm oil producers are not vulnerable to consumer pressure that can be exerted on more well-known brands through actions such as boycotts.

"You'll never see them anywhere in the United States," says Brownell, "but enter the supermarket and the food you buy – the chocolates … the chips, the snacks – contains palm oil These different brands, Nestle, Mars and others, are the main buyers. "

[ad_2]

Source link