[ad_1]

I remember being 13 years old and sleeping at a friend's house. I vaguely used the term "friend" because, years later, I realized that most of these girls were never really my friends. Making his bed in the morning, my host reached out and snatched something from the pillow.

"Yuck, yuck! Yuck! Disgust! Shouted it.

"OMG! What is it?" We all shouted.

"EUGH! There are pubes in my bed.

"Ugh, gross."

"No, hang in there, these are just Emma's hair."

Shouts of laughter.

I wanted to die. The sensation was accentuated by the disparity between my own hair and that of my host, hair that I secretly coveted. It was all right, a brilliantly shining black, that hung all along his back; she was complimented on it all the time. Her hair framed her eyes with an almost caricatural blue, a particular blue that exists in Ireland.

Until the late 1990s, being black and Irish had to have unicorn status – with the exception of everyone who loves unicorns. Many half-breeds I met, certainly those who were older than me, had grown up in institutions. They were often the "illegitimate offspring" of Irish women and African students. Not to dwell on the subject, single mothers were generally treated in Ireland, Ireland. Add the shame of a black child and you will not really be able to sink further down. Although it was not my experience, there was still a strong stigma badociated with darkness. Black child with tight hair, having grown up in a white country, homogeneous and socially conservative, my hair was a constant source of shame. I became obsessed with her, imagining that, if it just looked "normal," I, too, could be too. I started crying most nights between the ages of 8 and 10, desperately craving the night to make her magic work and turn my "tough" curls into the straight, straight hair that I deserved.

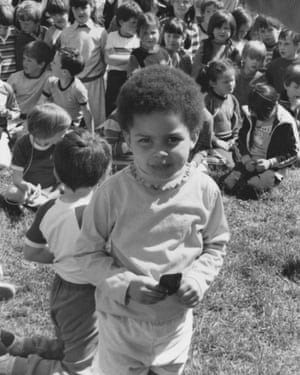

In Dublin, five years. Photo: photo courtesy of Emma Dabiri

I remember learning by the age of half that I was "lucky enough to be pretty," which meant that I could "almost get myself out of the deal by being black". I still have jokes about the need for a flash to take a picture of myself or the clbadic comparison of my skin tone with dirt, but it's my hair that has remained unforgivable. Anything that could be done on my part to disguise, manipulate and maim him was to be considered. The concept of letting the way he grew up was inconceivable.

The world around us is fueling a powerful narrative about hair and femininity. From fairy tales to commercials, to movies and video clips, our icons tend to be locked. For a long time, long hair has been one of the most powerful markers of women.

But this is not how Afro hair grows; he usually grows up. Of course, femininity – just like beauty – remains a specific cultural project, and certainly not a project designed for black women. Nevertheless, we expect to comply with these standards, and woe to us if we can not.

Growing up, I rarely saw black women on television (or anywhere else), with a few exceptions: Neneh Cherry, and Hilary and Ashley Banks of the famous Prince of Bel-Air. Cherry, in particular, I was trying to mimic her, but her big black curls that were thickening around her shoulders, as well as her curvy brown hair and the shiny black, ultra-smooth strands of Ashley were not that make me worse. These women had hair that seemed as inaccessible to me as my white counterparts.

***

The pressure to comply with European standards of beauty is much more than a type of vanity "that is always green". Barely a month seems to flow without further news about a black child excluded from school for carrying the hair in its natural form. In 2016, protests erupted after girls at Pretoria High School in South Africa chose to challenge the rules that kept their natural hair "messy". Two weeks later, a US federal court ruled that it was legal to dismiss an employee for dreadlocks, finding them "unprofessional".

And while it may seem unimaginable that a grown-up or even an adult is aggressive towards a child based on the texture of his hair, this happens more often than you think. Consider Blue Ivy, the eldest daughter of Beyoncé and Jay-Z, and the subject of innumerable memes and messages on social networks calling her "ugly". Why? Blue Ivy's biggest crime seems to be not being born with hair that has the texture of one of her mother's tissues. She has the audacity to have well-curled hair, only black hair. However, some people were so irritated by Blue's hair that a petition called "Comb Her Hair" was launched at the age of two.

When you look at how Blue Ivy and North West, Kanye West's daughter and Kim Kardashian, are opposed in these conversations, it's all the more sinister. Both children have fair skin. However, North is declared infinitely superior by adult men and women, partly because of her ambiguous racial traits, but mostly because of her hair: a very loose loop that makes it easy to get a long, straight look. In a 2015 article titled How Northwestern Curly Styles Inspire a Generation of Natural-Haired Girls, American Vogue stated that this two-year-old was an "icon" of natural hair.

The phenomenon we call colorism is not limited to the complexion: the texture of the hair and other characteristics play a role in determining the proximity of whiteness and whiteness. But many people with "good" hair, the looser loop badociated with mixed ancestry, have had the pain of not knowing how to care for them properly, especially those with a primary white care provider. All black hair requires knowledge, skills and products that are not always easily accessible. Today, in a multicultural and globally connected London, I still see Métis children with dry, tangled hair. I'm not talking about messy hair – I'm not a precision maker – I mean hair that, like my child, has clearly never been oiled, and rarely caught.

People often have questions about the education of children of mixed ancestry. One of the most practical tips I can give is to learn how to oil and comb their hair. When I was growing up, there was no information online and no suitable hair product in Ireland. The few people I managed to get my hands on came from my mother's work trips to the long-torn dockyards of Liverpool. She was one of the first people to import casual clothes (their status went to the vintage level) in Dublin. However, she was white, with little knowledge or experience in black hair care. So, unless one of her black girlfriends – who were absolutely not hairdressers – combed my hair or texture, these were rather left in a bun, a style totally unsuitable for her texture (that is, a mess).

Later, my mother often made great efforts to take me to the UK to get my hair done, even if the money was tight. I sneakily suspect that the permanent Jheri curl for which I traveled to London, a gift of her 12th birthday, puts me in the running as one of the first people to have soiled the cushions and couches of the early 1990s in Dublin with my loop activator.

Even my mother's friends were more used to applying chemicals than to taking care of hair in their natural state. I remember a particularly traumatic texturing attempt. A friend of my mother left the solution longer than recommended to take into account my unusually challenging bounce. The immediate result was long, silky waves. I was ecstatic. The next morning he went out by hand.

Although my hair was chemically relaxed for about 15 years, I knew or did not care about what was going on in my head. The burns were a recurring reality – almost every relaxant left some crusts on my scalp. But it was like insignia of honor, testifying to the fact that the relaxer had taken. Like most of my peers, I ignored the reported links between the chemicals used in the straightener and cancer, fertility issues and the development of fibroids. This cognitive dissonance horrifies me now.

***

Around 2010, I discovered a website called Black Girl with Long Hair (BGLH), founded in 2009 by American writer Leila Noelliste. It was the first time I really saw my recognized texture, much less celebrated – not only bright but shiny curls, but also soft and elastic naps that can be twisted, stretched, curled and curly to take n & # 39; Any form. I have introduced all these beautiful sisters with a very chic look, with their natural hair. And if they could do it, me too

A photograph: Silvana Trevale / The Guardian

Many women insist that their decision to go natural is not explicitly political. The fact that they even have to say it shows how much we still consider that black hair is normal. But my own decision to stop relaxing my hair was policy. I realized that as an adult woman, I did not know my own hair. I did not know his natural appearance and I did not live up to his requirements.

Once you straighten your hair chemically, you can not loosen it, you have to cut it. But I was just not ready for short hair. The texture was pretty serious – but willingly to return to a short Afro, to concede the victory to an enemy long overpowered, was unimaginable. So I stopped smoothing my hair but let my roots grow for a year before cutting the smoothed ends. The following year (2012), I became pregnant and finally gave in to it.

I had various motives. They say that your hair grows fast during your pregnancy, but it was more than that. I knew that if I had a girl, it was crucial that she did not grow up with the same distorted concept of beauty that I had. If I had a boy, such enlightenment was just as crucial, if not more so.

Despite these BGLH women who looked bomb, I still felt that natural hair did not suit me, at least not as much as my long slender locks. But, for the cause, I resigned myself to a future of feminist badly fagotée. It's amazing for me to remember that even at this point I did not see myself as attractive with unstressed hair.

My reunion with my natural hair and the birth of my son proved that my body was capable of things that I would never have imagined possible. Subtly, over time, I stopped tolerating my hair to enjoy it, to love it. I wonder if the freedom, the volume and the height found in my hair have shifted the energy around me. (It is said that many African groups badociate hair height with significant power over divine power.)

My hair is now usually braided in a certain way. Another misconception about black hair is that, for them to be "natural", they must be worn in afro. In traditional African cultures such as Yoruba, which is my paternal ancestry, women rarely left their hair unmolded; it would usually be braided (Irun Didi) or threaded (Irun Kiko). In practical terms, this is because letting it "stay" too long results in loss of moisture and entanglements. Not to mention the braiding also looks majestic.

The gains are never absolute, but it seems like big changes are coming. Overall, there is a movement of black women saying: we have enough; we want to be accepted to look like ourselves. Until recently, we did not see natural hair on our television screens. Textures like mine have remained hidden, forbidden. Last year, Black Panther marked a turning point in the feminist realm: female characters were geniuses of technology and warrior commanders – and they had tight afro hair, a first for a major production in Hollywood. He showed our hair as beautiful but, more than that, he showed it as Ordinary. If I had grown up seeing women with hair like mine on the screen, it would have made me proud – and much less alone.

• This is an excerpt from Emma Dabiri's Do not Touch My Hair (Allen Lane, £ 16.99). To order a copy for £ 13.99, including postage and packaging, visit guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846.

If you would like a comment on this article to be considered for inclusion on the Weekend magazine's newsletter page, please send an e-mail to [email protected], indicating your name and address (not for publication) .

Source link