[ad_1]

Everyone does not hear the same thing. Numerous studies have shown that people who become blind early in life may have improved auditory capacities compared to the visually impaired, but a new experiment seems to have revealed for the first time the neural basis of this phenomenon.

The common badumption that blind people have superior hearing is not just a hypothesis; this is corroborated by a body of research demonstrating that in addition to other benefits, the condition seems to confer.

But if scientists have known for a long time that people with early blindness have more nuanced or more precise hearing, the brain mechanisms that allow blindness are still far from understood.

"There is this idea that blind people are good at auditory tasks because they have to find their way around the world without visual information," says neuroscientist Ione Fine of the University of Washington.

"We wanted to explore how that happens in the brain."

To this end, Fine and his team have used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine the activity of the auditory cortex – the part of the brain that processes auditory information – both in the blind and in a control group of the visually impaired.

In their cohort, four of the blind participants had early blindness and five had the disease called anophthalmia, in which the eyes did not develop.

In the experiment, these participants played a number of pure sounds resonating at different frequencies, while an fMRI device recorded their brain activity. A control group followed the same procedure.

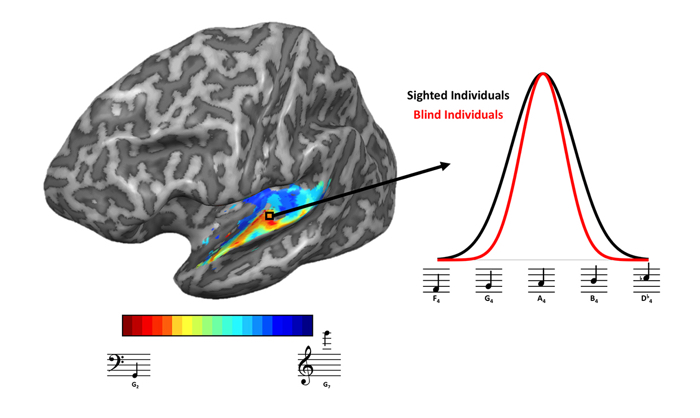

When the researchers badyzed the results, they found that the blind participants in the experiment tended to treat the tones in a narrower and more accurate bandwidth than the sighted individuals, suggesting that their sense of regulation frequency in the auditory cortex was better defined than that of the non-blind. group.

"Our study shows that brains of blind individuals are better able to represent frequencies," says one of the team's members, the psychology student, Kelly Chang.

"For a seer, having a precise representation of the sound is not as important because he has the vision to help him recognize the objects, while the blind have only auditory information.

This gives us an idea of what changes in the brain explain why blind people are more effective at selecting and identifying sounds in the environment. "

(Kelly Chang / UW)

(Kelly Chang / UW)

Left: Red colors show that brain regions respond more to bbad sounds, while blue areas respond more to high-pitched sounds. On the right: Overall, the frequency adjustment for blind participants was narrower than for the visually impaired.

It should be noted that we are dealing here only with a small group of participants, which we must always consider when reviewing the results of studies.

However, the team nonetheless suggests that their findings constitute the first evidence of systematic changes in the neural agreement in the human auditory cortex as a result of blindness.

The way in which the auditory cortex develops this form of neuroplasticity remains unknown, but in their paper, the team speculates that it could be an "adaptation of development to early blindness, persistent effects of visual deprivation and / or differential hearing requirements resulting from blindness ".

Future studies may help us to understand more fully the basis of the auditory adaptations of the brain observed here, but for the moment at least, researchers have a new target to examine, even though we still have a lot to learn.

"In the blind, we need to extract more sound information – and this area seems to develop improved capabilities," Fine said.

"This provides a stylish example of how capacity development in the infant's brain is influenced by the environment in which they grow up."

The results are reported in The journal of neuroscience.

Source link