[ad_1]

This article, written by Jade Savage, of Bishop's University, was originally published in The Conversation and is republished here with permission:

You may have noticed that by the first signs of spring, many media messages reminded you that it was also the beginning of the tick season.

Ticks are not new in our landscape, but rapid climate and environmental changes are driving northward expansion and explosive population growth for some species such as Ixodes scapularis – commonly called the deer tick or the blacklegged tick transmitting Lyme disease – in eastern North America.

So, it's not just an impression; there are now more ticks and some can transmit harmful pathogens. Can you blame someone for being a little worried?

Even though I spent most of my childhood hunting for insects in southern Quebec, I was in my thirties when I met my first local tick. I'm nostalgic for the days when ticks were not a parent concern, but I'm delighted to be living in a time when technology has enabled my team to create eTick.ca – an online identification platform. based on images allowing us to quickly inform anyone of the risks badociated with a tick found.

Butterfly Inspiration

A number of services are available across the country to help citizens get the information they need on ticks and tick-borne diseases.

These services, which may include identification procedures by agencies mandated by local governments, vary from province to province. When they are available, they usually involve the examination of specimens, a procedure that can take a long time, with postal and bureaucratic deadlines being mandatory.

With the steady increase in the number of specimens submitted each year through the usual channels, these procedures are no longer sufficient. New problems require new solutions.

In 2015, we created a pilot version of the citizen-science project eTick.ca in Quebec to solve this bottleneck problem and to demonstrate that tick species could be identified from images, with great precision. The experiment was a great success and in 2019 we reorganized the user interface and expanded our geographic scope to include Ontario and New Brunswick. Hope that other provinces will be added over the next year.

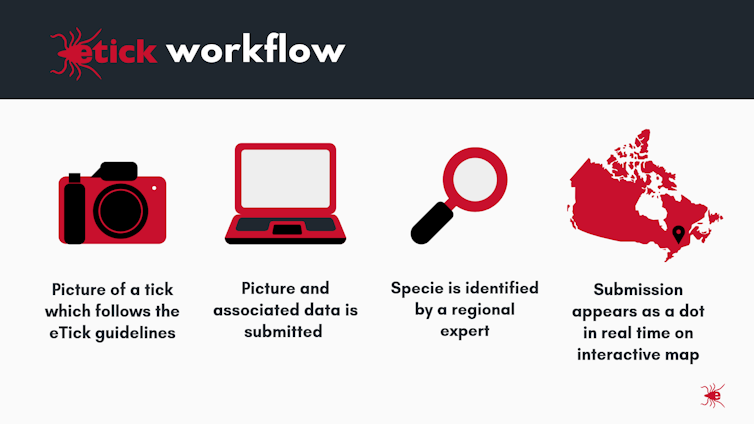

Our workflow is simple and primarily inspired by ebutterfly, another citizen science initiative developed in Canada.

When you find a tick, you upload a picture of it to eTick.ca with information on where and when it was found.

A provincial expert is then automatically notified and as soon as your image is identified, two things happen simultaneously: you receive a personalized information message and a point appears in real time on our public interactive distribution map. Submission takes less than three minutes and the identification process is usually completed within 24 hours of submission.

Although identification at the species level is excellent from a scientific point of view, it does not mean much for most people. Since then, we have developed messages that inform citizens not only of the species they have found, but also of their medical and veterinary relevance and provincial guidelines for the protocol to follow after a tick bite.

These messages and some of the new content found on the platform were developed in collaboration with partners from the Universities of Ottawa, Guelph and New Brunswick, as well as federal and provincial public health agencies (Quebec, Ontario and New Brunswick). The project is financially supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Why is quick identification important?

There are more than 40 species of ticks in Canada and only a handful of them are of medical importance. Knowing that the tick you found on your daughter this morning has no medical relevance will certainly be a big relief.

On the other hand, if you have been bitten by a tick known to transmit the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease, in an area deemed to be at risk, you may be able to claim a single dose of preventative antibiotics that would prevent the development of an infection if the tick was infected.

This approach, called post-exposure prophylaxis, is time sensitive: antibiotics must be administered within 72 hours of tick elimination to be effective.

Distribution map updated in real time

By indicating where the tick was found, the public is directly involved in the tick monitoring and tracking process. The fact that the recordings appear on a map in real time allows scientists to examine the timing of tick activity as well as the presence and abundance of different species as they appear, instead of wait for the end of year reports.

For hunters, campers, gardeners and others who enjoy outdoor activities, the map provides information on the presence of ticks in their place of residence or in an area they plan to visit and recalls that Prevention is always the best solution.

With better surveillance and rapid response, the health risks badociated with growing ticks in Canada could be better managed.

This is an important step in adapting to the growing number of threats posed by climate change. And, after all, the outdoors is made to be appreciated.![]()

– Jade Savage, Professor of Biology, Bishop & # 39; s University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source link