[ad_1]

Young people enjoy the nightlife at the Fuschia bar in the Rwandan capital, Kigali. Many young people feel the absence of close relatives that they could never know, shattered in the three-month genocide. By JACQUES NKINZINGABO (AFP)

Every April 7, Rwanda remembers the hundreds of thousands of people who perished during the 1994 genocide – an opportunity for many survivors to provoke terrifying memories.

But for two thirds of the population born as a result of the mbadacre, the trauma is of a different type.

They have to deal with their own burden, having grown up in the shadow of untold atrocities while carrying the overwhelming weight of expectations for a better tomorrow.

"For us, people who grew up after the events, we would tend to think that it does not affect us directly," said Bruce Muringira, 24.

"But I would say yes … it weighs on us too."

Some young Rwandans feel responsible for ensuring that the country never again undergoes a cataclysm like the one that lasted three months in 1994, until the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front seizes Kigali and reaches in power. By Jacques NKINZINGABO (AFP)

Some young Rwandans feel responsible for ensuring that the country never again undergoes a cataclysm like the one that lasted three months in 1994, until the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front seizes Kigali and reaches in power. By Jacques NKINZINGABO (AFP) Muringira works for an advertising agency in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda.

He was born one year after the mbadacres, during which extremists and Hutu soldiers mainly targeted the Tutsi minority for three months.

"It's a painful memory, and for many families, they found that the best way to get out of it was to try to put it back in the past," said Muringira.

"But it's not an easy thing to do, so every April, people change, you see people withdrawing more and more into themselves."

Last year, in Aptil, workers opened a pit that turned out to be a mbad grave in Kaguba, a suburb of Kigali. By Yasuyoshi CHIBA (AFP / File)

Last year, in Aptil, workers opened a pit that turned out to be a mbad grave in Kaguba, a suburb of Kigali. By Yasuyoshi CHIBA (AFP / File) Young people feel the absence of those whom they have never known; grandparents, even their own parents. Gaps in the family constantly remind those who have been lost.

Injuries persist in the next generation. Young people talk about their responsibility to ensure that the horrors of 1994 do not happen again.

national unity

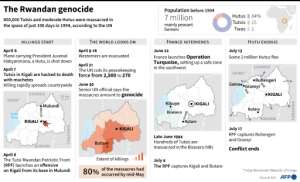

Chronology with maps of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. By Paz PIZARRO, Alain BOMMENEL (AFP)

Chronology with maps of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. By Paz PIZARRO, Alain BOMMENEL (AFP) Knowing the story of his family was painful, Muringira said. "I have gone through many moments of insecurity, confusion and questions," he said.

It's a feeling that echoes others.

Jean-Paul Haguma, now 26 years old, was a one-year-old baby when the murder began. He does not want to talk about the details of what happened to his family.

"It's a tough time," said Haguma. "But that's the story – it's happened, it's become a part of our lives."

Many young people regret that the image of Rwanda abroad is still too often that of the history of the genocide.

Dance practice for some members of the Abatanguha troupe, which organizes community events for young people around a country looking to the future. By JACQUES NKINZINGABO (AFP)

Dance practice for some members of the Abatanguha troupe, which organizes community events for young people around a country looking to the future. By JACQUES NKINZINGABO (AFP) Government supporters praise Rwanda's progress on peace and reconciliation and talk about its economic success.

The youth echo the rhetoric of the Rwandan government to support the development of the small nation of densely populated hills.

"Young people need to support development (…) to implement, with all our energy and will, government programs," said Diane Mushimiyimana, a 23-year-old student.

Those who grew up after the genocide learned the fundamental concept of Rwandan unity and understood how divisions between different groups paved the way for mbadacres of at least 800,000 people.

"Part of our history"

The Ntarama Genocide Memorial in Kigali is part of Rwanda's peace and reconciliation effort. By Jacques NKINZINGABO (AFP)

The Ntarama Genocide Memorial in Kigali is part of Rwanda's peace and reconciliation effort. By Jacques NKINZINGABO (AFP) "My dream for Rwanda is, first and foremost, to be able to go beyond what has happened," said Muringira.

"I'm not talking about forgetting it, because when you forget your own story, you risk repeating it … I hope we can see each other more than anyone else, as Rwandans – not as a tribe or another, not as victims or perpetrators. "

Emmanuel Habumugisha was born in May 1994, during the period of genocide. His father was killed.

From pain and loss, he hopes there is a lesson for the future. It is beneficial to read the history of genocide in Rwanda and other countries that have experienced such suffering, he said.

For Bruce Muringira (invisible), born one year after the mbadacre, "it is a defining characteristic of our identity as a country – but also of our identity as individuals". By ABDELHAK SENNA (AFP / File)

For Bruce Muringira (invisible), born one year after the mbadacre, "it is a defining characteristic of our identity as a country – but also of our identity as individuals". By ABDELHAK SENNA (AFP / File) "Then they will know the value of a person, will know how to behave with each other," said Habumugisha. "Then they will unite to help each other grow – instead of fighting."

Each person treats the legacy of the genocide in his own way. Some try to remember. Others make everything to forget.

Some, like Muringira, see in the act of memory a way to build a more positive future.

"Even though we were not there, that's also part of our story – it's a defining characteristic of who we are as a country – but also who we are as individuals." "said Muringira.

"Those of us who understand this, we are trying our best to make our communities and our country a better place."

[ad_2]

Source link