[ad_1]

AAfrican churches opened their doors in London from the 1960s, followed by a second wave in the 1980s. Migrants, mostly from Nigeria and Ghana, sought to create communities and maintain cultural ties with their country of origin by founding their own churches, often in private homes, schools and offices.

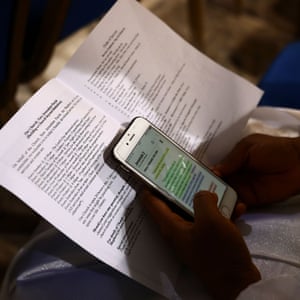

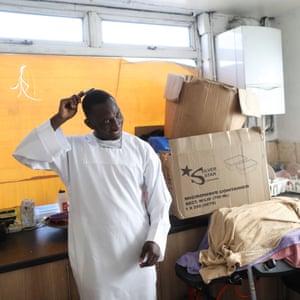

On a Sunday morning gray and cold, in a street lined with construction sites and closed storage, songs of prayer in Yoruba, language of West Africa, come out of an old warehouse which is now a church. The congregation, almost entirely dressed in white robes, continues to grow and has about 70 people. Musicians playing drums, a keyboard and a guitar accelerate the rhythm of the hymns. Some women prostrate on the floor in prayer. In the small, formerly industrial building whose interior is lit by touches of golden paint, a speaker reminds the group of a list of prohibited activities – no smoking, no alcohol, no black magic .

The new Jerusalem parish

In a street, a pastor throws holy water on the car of a woman who wants a blessing to guard against the risk of an accident. The bustling scene of Christ's heavenly church is repeated in half a dozen other Christian African temples in the same dark street and on the adjacent roads – a corner of the thriving African church community South London.

About 250 black majority churches would operate in the Southwark borough, where 16% of the population identifies with the African ethnicity.

Southwark represents the largest concentration of African Christians in the world outside the continent with more than 20,000 worshipers attending the new black majority churches every Sunday, according to a 2013 study by the University of Roehampton.

Reflecting the different waves of immigration to Britain in the 20th century, these African places of worship followed the Caribbean churches that emerged in the late 1940s and 1950s when workers and their families arrived from Jamaica and from the United States. 39, other former British colonies.

The house of praise

-

Dancers dance during the service of "Super Sunday" at the Church of the House of Praise. The church, which was once a theater and a bingo hall, is one of the largest in South London. The services, mainly frequented by followers of Nigerian origin, are recorded with television cameras.

As African communities grew, churches moved into larger halls, bingo halls, cinemas and warehouses, bringing together congregations of up to 500 people where services are broadcast online. by volunteers equipped with video cameras.

There is a stark contrast to the empty benches of many traditional churches in the Church of England, where congregations have been in decline for years.

"We pray for this country," said Abosede Ajibade, a 54-year-old Nigerian who moved to Britain in 2002 and works for an office maintenance company.

"The people here have brought Christianity to Africa, but it no longer gives them the impression of serving Jesus Christ."

The Christian Church of the Apostles of Muchinjikwa

-

Mbad baptism on the waterfront at Southend-on-Sea. Church members travel to Southend-on-Sea from across the country, including Scotland, to join members from London, Leeds and Leicester for an annual ceremony.

Anyone traveling to South London on a Sunday morning will see worshipers, often dressed in shimmering African clothing, and then head to churches of different worship styles.

The hymns are sung only in African languages in some temples or in English only. Some pastors ensure that the faithful take baptisms in total immersion in the cold of the Channel. Others think that when devotees suddenly begin to speak in unknown tongues, it marks the presence of the Holy Spirit.

The eternal sacred order of the cherubim and the seraphim church

Research conducted by the University of Roehampton has revealed that many churches have in common a desire for professional development, a commitment to spend three hours or more in Sunday service and a generally very noisy worship.

"This is how we express our joy and gratitude to God," Andrew Adeleke, senior pastor at the House of Praise, one of Southwark's largest African churches, in an old theater.

"The church is not supposed to be a cemetery," Adeleke said. "It's supposed to be a temple of celebration and worship and the beauty is to be able to express our love for God, even when things are not perfect in our lives."

For some, the noise generated by amplified services is a problem, resulting in complaints from residents to local authorities. However, many churches face greater challenges than their unhappy neighbors: some provide food to those who are struggling to make ends meet or who work with youth at risk of being recruited by gangs.

Andrew Rogers, Senior Lecturer in Practical Theology at the University and author of the research paper, Being Built Together, said that pastors had to reconcile the preservation of the African identity of churches while appealing to the First generation immigrant children, many of whom had never lived outside of Britain. They generally have a more liberal worldview than it can be difficult to reconcile with conservative Pentecostal teachings.

Rogers was reminded to have spoken to a pastor who had lamented not being able to talk about religious miracles to his children.

"If the church does not adapt, it will go away and look elsewhere," said Rogers.

Source link