[ad_1]

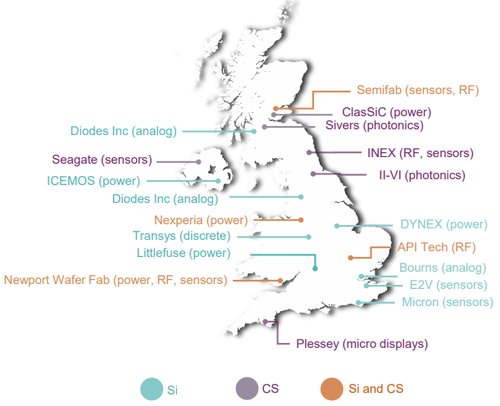

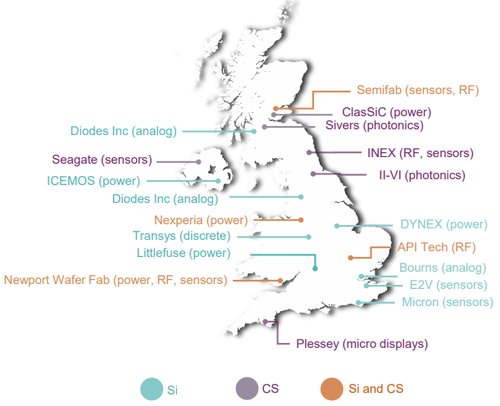

When it comes to chip shops, the UK is spoiled for choice. Some 19 ‘fabs’ that produce semiconductors of one variety or another are sprinkled across the country, from Glenrothes in Scotland to Plymouth in the southwest.

It is even better served by the designers of high end silicon chips used in the most sophisticated gadgets. “We have the second-highest number of design companies outside of the United States,” says Andy Sellars, director of strategic development for Compound Semiconductor Applications Catapult, a non-profit research and technology association that advises on industry and government on semiconductor strategy.

Cambridge-based Arm, which designs processors used in most of the world’s smartphones, is perhaps the UK’s brightest semiconductor asset. But other design gems include Imagination Technologies, XMOS, and Graphcore. Based in Bristol, the latter works on what Sellars describes as the most complex microprocessor in the world. “It’s an IA microprocessor with 59 billion transistors,” he says. “Your phone’s chip is about 2 billion, so that’s about 30 times the complexity.”

Absolutely fabulous

Notes: Si means silicon; CS stands for compound semiconductor.

(Source: CSA Catapult)

Still, there is a big gap. None of the UK factories have the capacity to make the most advanced silicon chips needed by the telecommunications, automotive and other critical industries. For the latter, its economy is heavily dependent on Asian manufacturers. In addition, most of the advanced components are produced by one company: TSMC from Taiwan. “There’s a lot of nervousness about TSMC making 85% of the high-end silicon chips,” Sellars says.

The deficiency has become even more glaring after Brexit and the recent clashes with China. Following its withdrawal from the European Union (EU), the UK is firmly outside an EU program to boost semiconductor production, and its relationship with the authorities. EU are deteriorating. Meanwhile, clashes with China over Huawei and the rights of Hong Kong citizens pose a risk due to China’s political interest in Taiwan.

Masters of miniaturization

Concerns about TSMC’s effective monopoly in this market extend far beyond the UK. As a “ foundry ” or subcontractor, the Taiwanese company manufactures chips for many of the largest tech and semiconductor companies in the United States, including iPhone maker Apple and Nvidia, a graphics chip designer trying to overcome regulatory opposition to a $ 40 billion Arm Takeover. Even Intel is now outsourcing the production of its most advanced chips to TSMC.

The Taiwanese foundry led the world in the miniaturization of transistors used in chips. Its advanced technology uses transistors that each measure just 5 nanometers (nm), or billionths of a meter. No other company is on this level, and only South Korea’s Samsung can match TSMC on the 7nm technology used in some 5G network equipment and smartphones. With its 10nm factory, Intel is about two generations behind TSMC, says Roslyn Layton, co-founder of China Tech Threat, an advisory group.

The growing importance of semiconductors to the global economy makes heavy supplier dependence seem hopelessly short-sighted. Worse yet, China’s land claim over the country where TSMC’s semiconductor factories are located. “The fact that China has designs in Taiwan made everyone very nervous about relying on TSMC for these silicon chips,” Sellars says. Arguably, the main US concern about a Chinese takeover of Taiwan is that it would allow China to block TSMC shipments to the West.

Light reading.

It is also a frightening prospect for other jurisdictions. Regardless of its role in the semiconductor value chain, any technology-driven economy would suffer badly if TSMC were cut off from Western companies. In telecommunications, in particular, Ericsson and Nokia, the only major Western manufacturers of 5G networking equipment, are likely customers of TSMC, experts say (neither company is disclosing the identity of its suppliers).

Hence recent US and European initiatives to boost semiconductor production in their own backyards. The United States had already made a commitment from TSMC last year to build a new smelter in Arizona. Then, last week, Intel unveiled plans to spend $ 20 billion to start its own foundry business in the same US state.

It came days after Europe announced its ambition to increase its share of semiconductor production from 10% to 20% of the global total by 2030. While Europe gave little indications of how, Intel’s plans might align with its interests. “I hope we will be ready to announce our next phase of expansion to the United States, Europe and other parts of the world later this year,” said Pat Gelsinger, new CEO of Intel. , in its recent press release.

Choice of chips

But all of this leaves an independent UK potentially at risk. Sellars, who is in talks with the government, says three approaches are currently being considered. The first is the status quo of relying on the free market while continuing to highlight UK design credentials. “Obviously, if TSMC shuts down, you’re in trouble and you don’t have access to it,” Sellars says. “And then you can’t make your cars, so it’s a bit risky.”

An alternative is to have a strategic partnership with a company like Intel. This could mean inviting the US company to build one of its international foundries in the UK, which Sellars thinks is a “great idea”. Otherwise, the UK could promise in advance to purchase a minimum amount of capacity in Arizona from Intel or the future European plant for a contract fee.

However, it could also come with some risk. Just weeks after Brexit became official, UK-EU relations are at an all-time low when it comes to coronavirus vaccine shipments. In short, the EU accused the UK of stockpiling vaccines destined for Europe and threatened to block vaccine exports to the UK in retaliation. It is not difficult to envision similar lockdowns and quarrels over semiconductors when there is a shortage.

For reasons of supply and demand, this is exactly the situation the world is currently facing. The boom in laptops, tablets and mobile phones has coincided with a water shortage at TSMC, crippling its production process. The auto industry has paid the price, according to Sellars. “TSMC prioritizes where the money is and it’s in cellphones and not in cars,” he says. “As a result, America is laying off people in the auto industry.”

Silicon production at one of TSMC’s facilities in Taiwan.

The third option for the UK would be a full-fledged investment in high-end silicon factories and “sovereign capacity,” Sellars says. Still, it would be a daunting task at the best of times. GlobalFoundries, America’s only major foundry, gave up trying to compete on transistor size a few years ago because of investment demands, Layton says. Today it focuses on the 22nm to 90nm range.

Earl Lum, a semiconductor expert at EJL Wireless Research, also doubts that Europe or the UK will be able to compete in this high-end market. “Who is going to pay 40 to 50 billion dollars a year to create a foundry equivalent to TSMC for Europe?” he told Light Reading. “You want a place with a lot of land that’s pretty cheap, and the other issue is how you’re going to train people to work in a wafer factory.”

Sellars generally agrees. “It’s not just the money,” he says. “One of the pieces of equipment costs $ 100 million, but you have to have people who have ordered and bought it before and the environment it comes in has to be clean. You need extreme expertise.” Importing it from elsewhere could be a remedy, he thinks.

Even so, the UK currently has a more interventionist government than it has seen in about 40 or 50 years. “We had successes and failures, and then in the 1980s we decided we wouldn’t do it anymore,” Sellars says. “It was about picking the winners and we’ve never been very good at it, but therefore some of those great strategic things don’t reside here.”

Government interventionism is already apparent in the telecommunications sector, where last year’s decision to ban Huawei from 5G prompted scratching of their heads over the lack of local alternatives. The authorities have set up a task force on telecommunications to explore options for market diversification which sells to operators such as BT, O2, Three and Vodafone.

The efforts are bound to come up against accusations of protectionism and unwanted state interference. And as it emerges from the coronavirus pandemic, the UK is heavily in debt with a national debt of £ 2.1 trillion ($ 2.9 trillion) and has little room for budget errors. A big bet on semiconductors might be a smart move in such an uncertain world, but it could backfire on us as well.

Similar Items:

?? Iain Morris, International Editor, Light Reading

[ad_2]

Source link