[ad_1]

Less than a decade ago, using an organ of an HIV positive person for an organ donation was a federal crime because of a law pbaded at the height of the AIDS crisis .

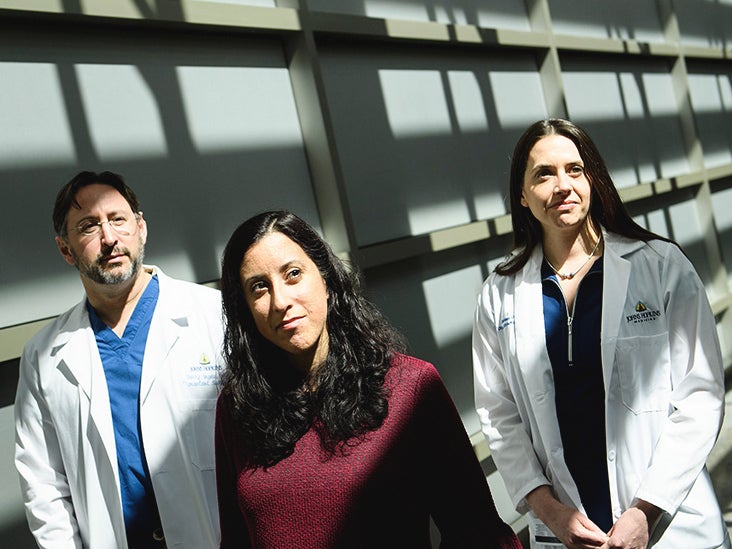

But last week, a medical team at Johns Hopkins Medicine made a major medical advance by performing the first successful kidney transplant from an HIV-infected living organ donor to a recipient who was also infected with HIV.

This procedure was the first of its kind in the United States and could potentially pave the way for better access to organs for people living with HIV.

The procedure was carried out on Monday, March 25th. The doctors successfully transferred a 35-year-old kidney from Nina Martinez to a recipient who wanted to remain anonymous, according to a press release.

"This is the first time in the world that a person living with HIV is allowed to donate a kidney, and that's huge," said Dr. Dorry Segev, Professor of Surgery at the Faculty of Medicine from Johns Hopkins University, in a statement. .

"An illness that was a death sentence in the 1980s has become such a controlled disease that people living with HIV can now save lives by donating kidney – it's amazing," he said.

The success of the transplant comes after recent advances in accepting donated organs from people living with HIV.

Just six years ago, HIV-positive organ transplants were not allowed in the United States. All this has changed with the 2013 HIV Organizational Equity Equity Act, led by Segev.

What exactly were the obstacles to accepting this type of transplant? The medical community as a whole has long been concerned that the presence of HIV can lead to complications for donors, such as kidney disease.

With improvements in antiretroviral therapy over the years, people with HIV can not only live a normal life, but the increased risk of kidney failure and other complications is reduced, said Dr. Hyman Scott, MPH, Medical Director of Clinical Research at Bridge. HIV and an badistant professor of clinical medicine at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF), told Healthline.

"In a similar way to screening for blood supply, all organ donors are screened for potentially infectious diseases," Scott said.

Screening is necessary because transplant recipients receive drugs to suppress their immune system so that their new organ is not rejected.

"HIV has long been an infectious disease that prevented anyone from giving an organ," Scott said. "Now, modern HIV treatments reduce these serious complications."

But Scott says medical advances in HIV treatment as well as organ transplant recipients have contributed to these transplants.

Scott says that HIV transplants have occurred before, but in deceased donors. The news of a live donor living with HIV, able to contribute without any complication – so far, Martinez and the recipient are doing well – changes the game.

Scott says this gives additional hope to people living with HIV who are in desperate need of organ donations.

Even for people who do not have HIV, it can be difficult to make an organ donation. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, more than 113,000 people in the country are on the national waiting list for organ transplants.

"In general, there is a shortage of organs to transplant. Unfortunately, there are more people on the waiting list for transplants than organs for individuals, "Scott said.

Living donors can help bridge the gap for people on transplant lists, who are waiting for an organ from a deceased donor.

"Allow a person who, out of altruism as a living donor in this case, or as part of someone who might be dead who was HIV positive and who wanted to donate their organs after death, I think, gives more opportunity in the hope for people living with HIV to be able to receive a transplant, "Scott said.

Since the adoption of the HOPE law, 116 kidney and liver transplants have taken place from deceased donors who are HIV-positive to the deaths of HIV-positive people, Kaiser Health News reported.

Dr. Alan Taege, an infectious disease specialist at the Cleveland Clinic, told Healthline that while the news of Martinez's donation was a significant step forward, the medical community still needed to be cautious.

Historically, he says, people with HIV have a higher risk of kidney failure. Taege explains that part of this is that there is a statistically "overrepresentation of African-American and minority patients in the HIV population" – groups that alone have higher risk factors. of diabetes and other diseases badociated with kidney disease.

"In the future, the debate will probably focus on the long-term consequences for a donor like this one who has HIV. Will they be at higher risk of kidney failure? What are the disadvantages of considering this avenue for transplantation? ", Is interviewed Taege.

He says that it is still a single test that has not been accepted as practical. Inevitably, the first of all that remains to be done will always be the subject of careful scrutiny, adds Taege.

"The result is that this will spawn another clinical trial where we can examine the feasibility of HIV-positive live donors for HIV-positive patients. Someone must always be first, have the idea, then someone must understand it and follow it, "said Taege.

Taege points out that the Johns Hopkins Medicine Group is a strong advocate for people living with HIV.

"Now everyone will look at the long-term results for this donor, among other things," said Taege. "One of the concerns that has been raised in the past is that an HIV-positive organ may contain a different strain of HIV virus that the recipient might not be able to handle with his or her medications."

He says these are normal issues that will need to be addressed as the medical community moves forward to find perfect ways for HIV-related organ transplants.

This transplant is likely to contribute to the ongoing destigmatization of HIV in this country. In the United States, there are an estimated 1.1 million people living with the virus, according to 2015 figures. .

Today, many people understand that people living with HIV can live and thrive and even donate kidney. Compared to the beginnings of misinformation, from the nature of the virus to the way it is transmitted, highlights a major cultural shift, says Scott.

Scott and Taege add that it is important to emphasize that people living with HIV can lead a long and healthy life.

For example, HIV-positive people who are on specific antiretroviral therapy can achieve an undetectable viral load. This means that they can not transmit the virus to HIV-negative bad partners, .

Rigorous public awareness campaigns on this subject have been instrumental in changing cultural perceptions, as well as treatment as a prevention method, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). It is a daily schedule of two drugs in a tablet taken by people who are HIV-negative but at risk of contracting HIV.

The US government recently announced its intention to eradicate new HIV and AIDS diagnoses nationwide by 2030, although the exact funding to do so has not been clarified.

Scott says that all this, with Martinez's kidney donation, is good news.

"I think all this reflects the evolution of HIV management and its perception by the world. People whose blood is contaminated with HIV have a very, very long life expectancy. It's not like in the 80s, when we diagnosed AIDS and the median survival was 18 months, "said Scott.

"In the decades that followed, the life expectancy of a person who is not HIV positive is now approaching a lot of his life," he added.

He says that Martinez's "wonderful altruism" is a big problem. The high visibility the news received was a "big deal," too.

Taege echoes these thoughts.

"We still can not cure HIV, but I think that, overall, the general public is convinced that all we can do to increase the number of organs in HIV-positive or HIV-negative patients is a good thing for the society. " he said.

In March, a team from Johns Hopkins Medicine performed a successful kidney transplant from an HIV-positive organ donor to an HIV-positive patient.

This procedure, the first of its kind in a living donor, is in line with the 2013 legislation that lifted the ban on transplants from HIV-positive deceased donors.

Infectious disease experts say the news is important as it may open up easier ways for HIV-positive people to receive the necessary organ donations. It also highlights the growing understanding of society and its destigmatization of HIV.

Source link