[ad_1]

Last year, a Danish study found a link between nitrates in drinking water and the risk of colorectal cancer (gut). This finding could have significant consequences for New Zealanders.

New Zealand has one of the highest rates of bowel cancer in the world. Recent data also show that in some areas of New Zealand, drinking water supplies have nitrate levels more than three times the colorectal cancer risk threshold identified in the Danish study.

This study, along with other research, raises an important question about the contribution that nitrate exposure to drinking water can make to New Zealand's high rates of bowel cancer.

Read more:

What explains the increase in bowel cancer among young Australians?

Implications for the health of nitrates in drinking water

Nitrate fertilizers are added to pastures and crops to accelerate plant growth. Much of it enters the waterways directly with rain and irrigation or through animal urine.

The Danish study, published in the International Journal of Cancer, featured a considerable number of participants and a prolonged follow-up period. It included 2.7 million people over the age of 23 and monitored their individual levels of nitrate exposure and colorectal cancer rates.

The results confirmed the most common suspicions that long-term nitrate exposure may be related to cancer risk. The researchers suggested that the risk resulting from the conversion of nitrates to a carcinogenic compound (N-nitroso) after ingestion.

The research found a statistically significant increase in the risk of colorectal cancer at 0.87 ppm (parts per million) nitrate nitrogen in drinking water. The risk increased by 15% to levels above 2.1 ppm, compared to those who were least exposed.

One of the main implications is that the current standard of nitrate for drinking water used in most countries, including New Zealand, is probably too high.

International standards for nitrates

The level of cancer risk (0.87 ppm) identified in the study is less than one-tenth of the current maximum allowable value (AMV) for nitrate-nitrogen of 11.3 ppm (equivalent to 50 ppm nitrate). This level has been used in many countries for decades and comes from the limit set by the World Health Organization. It is based on the risk of "baby blue syndrome" (infantile methemoglobinemia, a disease that reduces the ability of red blood cells to release oxygen into the tissues), but not the risk of cancer.

The rates of bowel cancer vary in New Zealand, the incidence being highest in South Canterbury, with an age-standardized rate of 86.5 cases per 100,000 population. . Cancer of the intestine is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in New Zealand and every year about 3,000 people are diagnosed and 1,200 die from it.

A recent epidemiological study estimated the contribution of a range of modifiable risk factors from "lifestyle" to colorectal cancer in New Zealand. In order of importance, these factors are obesity, alcohol, physical inactivity, smoking and consumption of red meat and processed meat. It would be useful to conduct further research to see if exposure to nitrates in drinking water should be added to this list.

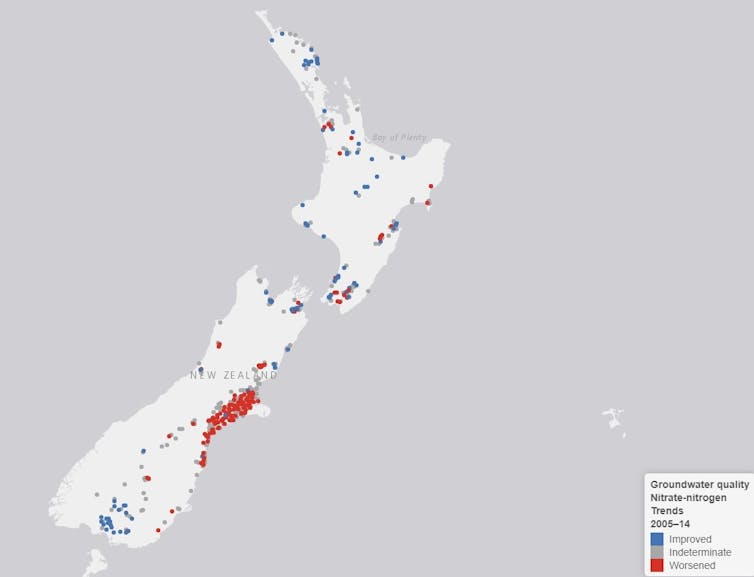

Ministry of the Environment, NZ Stats, CC BY-ND

A recent Fish and Game New Zealand survey of drinking water sources in the Canterbury area found that nitrate levels in drinking water from groundwater in intensive growing and horticultural areas are already high and increasing. The results are consistent with data from the Canterbury Environment Regional Council. The latest groundwater report showed that half of the wells they monitor had values greater than 3 ppm nitrogen / nitrate, more than three times the threshold for triggering the Danish cancer risk study. colorectal.

Data from Christchurch City Council shows that out of 420 samples taken in the last five years from 2011 to 2016, 40% exceeded 0.87 ppm.

Read more:

You've heard about a carbon footprint – now is the time to take action to reduce your nitrogen footprint

Impact on ecosystems

When nitrates enter the waterways, they accelerate the growth of algae. Freshwater scientists have long advocated limiting nitrates to limit algal blooms, but restrictions have been slow and, in some areas, non-existent. An important coincidence is that the Australian and New Zealand recommendations for healthy aquatic ecosystems for nitrates are 0.7 mg / l nitrate nitrogen, which is close to the level required to stay below the risk value of colorectal cancer found in the Danish study.

The Canterbury region is an illustration of the problems that New Zealand, the central and local governments, and the protection of groundwater and surface water have become unable to cope with. These failures can not be attributed to a lack of awareness since these results were predicted several decades ago. For example, in 1986, the Department of Public Works predicted nitrate contamination, which we now view as a consequence of regional irrigation systems. He made it clear that alternative drinking water resources should be found for residents of Canterbury.

In addition to environmental and health concerns, another concern is that public fears about safe drinking water are a boon for bottling companies, who have free access to the cleanest water from New Zealand.

While many New Zealanders face significant and growing water treatment costs, bottlers pay virtually nothing. The only cost, aside from the bottling costs, is a single 35-year right granted by the Regional Council. This anomaly underscores the urgent need for the government to set stricter limits on nitrate loss and to address water ownership issues in New Zealand.

In conclusion, in many parts of New Zealand, surface waters are heavily contaminated with nitrates due to intensified agriculture. These high levels undoubtedly affect freshwater ecosystems and biodiversity, but can also affect human health.

At a minimum, public health authorities should conduct a systematic survey to badess current levels of nitrates in New Zealand's drinking water, including those that are not part of the systemically monitored network. This information could then be used to provide a quantitative estimate of the colorectal cancer burden in New Zealand attributable to this risk.

Source link