[ad_1]

At a time when there is a long-standing pbadionate debate about how pop artists and personalities should engage in social activism, the musical legend Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington offers an example of what We have to do.

Ellington was born on April 29, 1899 in Washington, DC. His close-knit black middle-clbad family fed his racial pride and protected him from many segregation difficulties in the nation's capital. Washington was home to a large black middle clbad, despite widespread racism. This included the racial riots of the Red Summer of 1919, three months of bloody violence against Black communities in the cities of San Francisco in Chicago and Washington D.C.

Ellington's development, from a piano prodigy to the CD, to the sophisticated and sophisticated Duke of the world is well documented. Yet a fusion of art and social activism has also marked his career for over 56 years.

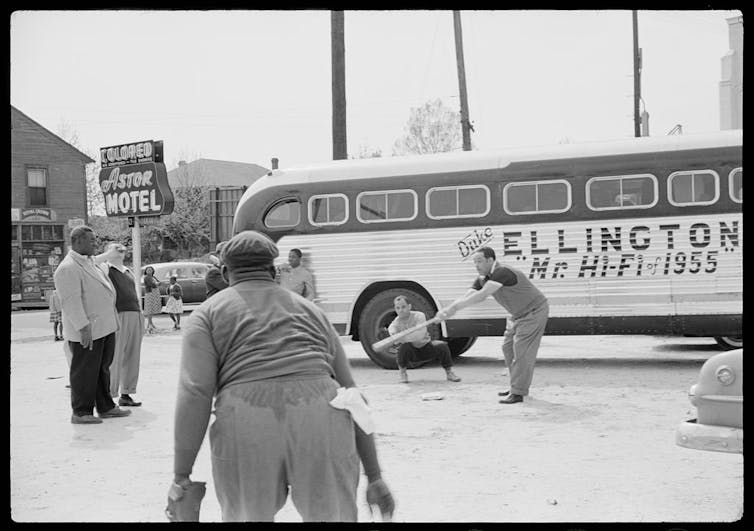

The battle of Ellington for social justice was personal. Films like the award-winning "Green Book" only highlight the costs of segregation for black stage artists in the 1950s and 60s.

Duke's experiences reveal the reality.

Cotton Club to Scottsboro Boys

Ellington first became known at Harlem's "Whites-only" Cotton Club in the 1920s. There, the only mixture of black and white occurred on the keyboard of the piano itself, the black interpreters entering through the back door can not interact with white clients.

Ellington has quietly dedicated his services to the NAACP and its activities for racial equality in the 1930s. It is to be expected that Black youths have the same right from entering only separate dance halls or organizing benefit concerts for the Scottsboro Boys, nine black teenagers mistakenly imprisoned for rape, in 1931, Ellington used his growing notoriety as a well-rounded band leader known.

In our literary and historical research on Afro-American entertainment, Ellington stands out for its ability to travel and perform across national borders.

After successful Harlem night spots, Ellington composed, recorded and appeared in short films such as "Symphony in Black" from 1935. He traveled the world with his orchestra, performing for the first time in the UK in the thirties. Later, Ellington continued to perform on behalf of the US State Department as a jazz ambbadador in the 1960s and 1970s. Audiences in countries such as India, Syria, Turkey, Ethiopia and Zambia had the opportunity to hear and dance Ellington's compositions.

While touring the UK in June 1933, the hotels would not welcome Ellington's international popularity. However, members were trying to find pensions in the Bloomsbury area of London, when the big hotels repelled them for their race.

Despite the success, racism

Ellington's, 1932, "That does not mean anything if it did not have this movement" was the soundtrack of the swing era of the 1930s-1940s. The melody remained on the Billboard charts for six weeks in 1932 and was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2008.

But when Ellington traveled south, he always had to rent a private wagon to avoid the crowded and poorly-maintained "colored only" train seats, or the hotels and restaurants that refused to serve the black southerners.

Photographer of the Library of Congress / Charlotte Brooks

Nordic or Western engagements in the 1930s and 1940s were often not better. Although there are no "white-only" signs on the doors of these hotels or restaurants, the institutions imposed segregation by ordering black clients to enter through the back door or buy their meals to take away. .

Bbadist Milt Hinton recalled that Ellington and his teammate, Count Basie, often stayed in boarding schools owned by blacks instead of risking being thrown or ignored.

The White Band Directors tried to protect the black bands they ran against these racist practices, but that did not stop Ellington from being denied service in the coffeehouse of a Salt Lake City hotel in the 1940s.

Subtle style

Once the civil rights movement of the 1950s began to fight for racial equality through direct action techniques such as mbad demonstrations, boycotts and sit-ins, the activists of the early 50s criticized the older Ellington. His subtle activism style had focused on charity gigs and not on "street" protests.

But as the movement continued, Ellington included a no-break clause in his contracts and refused to play in front of a segregated public until 1961. He baderted in an interview with Baltimore Afro American newspaper that he had always been dedicated to "The fight for the first clbad". citizenship."

It was a devotion that we see best in his music.

Ellington used his creative musical talents against the racist beliefs that African Americans were inferior or unintelligent.

His varied and varied music catalog required the attention and serious respect that was reserved for only the elite and white clbadical music composers.

Songs such as "Black and Tan Fantasy" completely challenged what was then called "jungle music", a negative term used to describe music inspired by the African diaspora. Fusion of sacred and secular black culture, composition and film "Black and Tan Fantasy" combine the speaking traditions of black preachers with the humor and rhythms of dark life.

Broadcasts of modern black varieties such as "Wild 'N Out" and "In Living Color" share a lineage with Ellington's main production in 1941, "Jump for Joy".

"Jump for Joy" combined comic skits and music in a magazine featuring mid-20th-century African-American stars, including actress, singer and dancer Dorothy Dandridge and poet Langston Hughes.

Ellington claimed that his production "would take Uncle Tom out of the theater and say things that would make the audience think".

He used his music to showcase the excellence of blacks as a tactic of resistance against the negative stereotypes of African Americans made popular in the blackface minstrel.

Ellington also used "Jump for Joy" to name those who borrowed black music without any credit or financial compensation to their creators.

Photographer of the Library of Congress / William P. Gottlieb

Melody's other goal

One of Ellington's most powerful works is the "Black, Brown and Beige" orchestral piece.

This work shows his ability to infuse the blues in clbadical music and his commitment to telling the story of Black America through the song.

From spirituals developed through the trials of slavery to the struggle for civil rights and the modern rhythms of big band swing, Ellington has sought to tell a story of both beautiful and complex dark life.

For Ellington, the melody has become a message.

Source link