[ad_1]

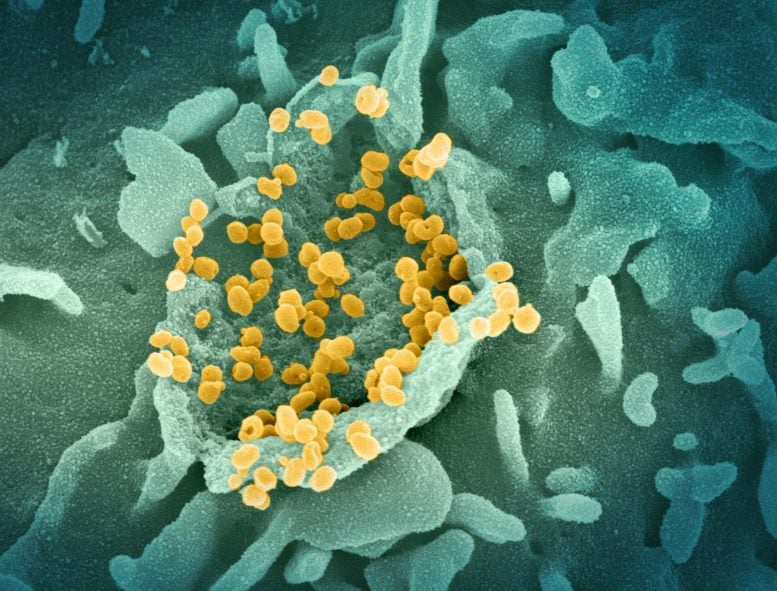

This scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 (round gold particles) emerging from the surface of a cell grown in the laboratory. Image captured and colorized at Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Montana. Credit: NIAID

Cells taken from patients at diagnosis who later developed severe COVID-19 show an attenuated antiviral response, research shows.

- Researchers studied cells collected by nasal swab at diagnosis for mild and severe COVID-19 patients

- Cells taken from patients who developed severe disease had an attenuated antiviral response compared to those who developed mild disease

- This suggests that it may be possible to develop early interventions that prevent the development of severe COVID-19

- The team also identified infected host cells and associated pathways for protection against infections that could enable novel therapeutic strategies for COVID-19 and other respiratory viral infections.

Over the past 18 months, researchers have learned a lot about COVID-19 and its viral cause, SARS-CoV-2. They know how the virus enters the body, enters through the nose and mouth, and begins its infection in the mucus layers of the nasal passages. They know that infections that remain in the upper respiratory tract are likely mild or asymptomatic, while infections that progress through the airways to the lungs are much more serious and can lead to life-threatening illness. And they identified common risk factors for serious illness, like age, gender, and obesity. But there are still many unanswered questions, such as when and where the course of severe COVID-19 is determined. Does the path to serious illness start only after the body has failed to control mild illness, or could it start much sooner than that?

Researchers from the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard; the Broad Institute at MIT and Harvard; Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH); MIT; and the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) have questioned whether this path to serious illness could start much sooner than expected – perhaps even as part of the initial response created when the virus enters the nose .

To test this, they studied cells taken from nasal swabs of patients at the time of their initial diagnosis of COVID-19, comparing patients who developed mild COVID-19 to those who progressed to more serious illness and had eventually needed breathing assistance. Their results showed that patients who developed severe COVID-19 had a much more attenuated antiviral response in cells collected from these early swabs, compared to patients who had a mild course of the disease. The article appears in the newspaper Cell.

“We wanted to understand if there were any pronounced differences in the samples taken at the onset of the disease that were associated with different severities of COVID-19 as the disease progressed,” said lead co-author José Ordovás-Montañés , associate member of the Klarman Cell Observatory on Broad and assistant professor at BCH and Harvard Medical School. “Our results suggest that the course of severe COVID-19 may be determined by the body’s intrinsic antiviral response to initial infection, opening new avenues for early interventions that could prevent serious illness.”

To understand the early response to infection, Sarah Glover of UMMC’s Digestive Diseases Division and her lab collected nasal swabs from 58 people. Thirty-five swabs were from COVID-19 patients, collected at the time of diagnosis, representing a variety of medical conditions from mild to severe. Seventeen swabs were from healthy volunteers and six from patients with respiratory failure due to other causes. The team isolated individual cells from each sample and sequenced them, looking for RNA that would indicate the type of proteins the cells were making – an indicator for understanding what a given cell is doing at the time of collection.

Cells use RNA as instructions to make proteins – tools, machines, and building blocks used in and by the cell to perform different functions and respond to its environment. By studying the collection of RNA in a cell – its transcriptome – researchers understand how a cell reacts, at that precise moment, to environmental changes such as viral infection. Researchers can even use the transcriptome to see if individual cells are infected with an RNA virus like SARS-CoV-2.

Alex Shalek, co-lead author of the study, fellow of the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard, and fellow of the Broad Institute, specializes in the study of single cell transcriptomes. His lab has helped develop innovative approaches to sequence thousands of single cells from low-input clinical samples, such as the nasal swab from COVID-19 patients, and use the resulting data to create high-resolution images of the the body’s orchestrated response to infection at the sample site.

“Our single-cell sequencing approaches allow us to thoroughly study the body’s response to disease at a specific point in time,” said Shalek, who is also an associate professor at MIT at the Institute for Medical Engineering & Science. , the Department of Chemistry, and the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research. “This gives us the opportunity to systematically explore the characteristics that differentiate one disease from another, as well as infected cells from those that are not. We can then use this information to guide the development of more effective prevention and treatment for COVID-19 and other viral infections. “

Ordovás-Montañés’ lab studies inflammatory responses and their memory, specializing in those found in epithelial cells – the top layer of cells, like those that line your nasal passages and are collected by nasal swabs. In collaboration with the Shalek lab and that of Bruce Horwitz, a senior associate physician in the Emergency Medicine Division at BCH, the researchers questioned how epithelial and immune cells respond to early infection with COVID-19 from the data of the unicellular transcriptome.

First, the team found that the antiviral response, driven by a family of proteins called interferons, was much more attenuated in patients who developed severe COVID-19. Second, patients with severe COVID-19 had higher amounts of highly inflammatory macrophages, immune cells that contribute to high amounts of inflammation, often found in severe or fatal COVID-19.

Since these samples were taken long before COVID-19 reached its peak disease state in patients, these two results indicate that the course of COVID-19 can be determined by the initial or very early response of patients. nasal epithelial and immune cells to the virus. The lack of a strong initial antiviral response may allow the virus to spread faster, increasing the chances that it can travel from the upper respiratory tract to the lower respiratory tract, while the recruitment of inflammatory immune cells could help cause dangerous inflammation in serious diseases.

Finally, the team also identified infected host cells and pathways associated with protection against infection – cells and responses unique to patients who developed mild disease. These results could allow researchers to discover new therapeutic strategies for COVID-19 and other respiratory viral infections.

If, as the team’s evidence suggests, the early stages of infection can determine disease, this paves the way for scientists to develop early interventions that can help prevent the development of severe COVID-19. The team’s work even identified potential markers of severe disease, genes that have been expressed in mild COVID-19 but not severe COVID-19.

“Almost all of our severe COVID-19 samples lacked expression of several genes that we would generally expect to see in an antiviral response,” said Carly Ziegler, a graduate student in the Health Sciences and Technology program at MIT and Harvard and one of the co-first authors. “If other studies support our results, we could use the same nasal swabs that we use to diagnose COVID-19 to identify potentially serious cases before serious illness develops, creating an opportunity for intervention early effective.

Reference: “Altered local intrinsic immunity against SARS-CoV-2 infection in severe cases of COVID-19” by Carly GK Ziegler, Vincent N. Miao, Anna H. Owings, Andrew W. Navia, Ying Tang, Joshua D. Bromley, Peter Lotfy, Meredith Sloan, Hannah Laird, Haley B. Williams, Micayla George, Riley S. Drake, Taylor Christian, Adam Parker, Campbell B. Sindel, Molly W. Burger, Yilianys Pride, Mohammad Hasan, George E. Abraham III, Michal Senitko, Tanya O. Robinson, Alex K. Shalek and Sarah C. Glover, July 22, 2021, Cell.

DOI: 10.1016 / j.cell.2021.07.023

Support for this study was provided by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the Richard and Susan Smith Family Foundation, the AGA Research Foundation, the New York Stem Cell Foundation, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institute on Aging, Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard, and other sources.

[ad_2]

Source link