[ad_1]

Every year, doctors can diagnose and treat cancer more and more sophisticated.

To date, cancer prevention in primary care has focused on modifying behaviors badociated with increased cancer risk – primary prevention – or increasing participation in national cancer screening programs, known as secondary prevention.

But if you are a person at high risk of developing cancer, there are approaches that can prevent its formation in the first place, known as chemoprevention. Chemoprevention can include the use of drugs to reduce risk, delay cancer development or recurrence, or even try to prevent it altogether.

Now he is entering general practice for specific groups of patients.

But all drugs have potential side effects and the disadvantages and potential benefits of cancer chemoprevention must be clearly explained to patients. And how these risks and side effects are explained to people is important.

Fill in the genetic whites of the predisposition to bad cancer

Read more

Researchers from the Primary Care Cancer Research Group at the University of Melbourne have developed a new way to communicate this information using diagrams called "expected frequency trees".

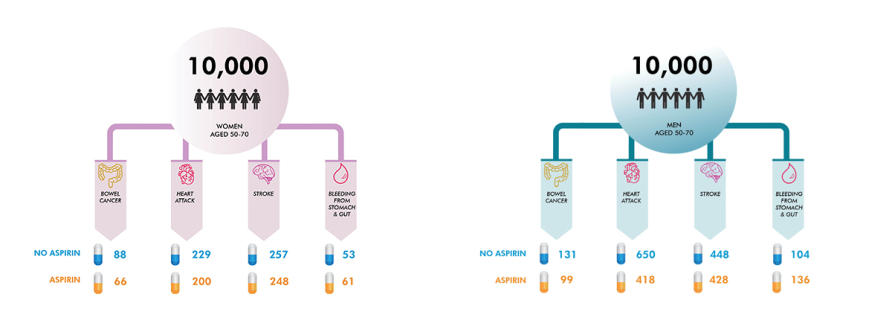

The team developed diagrams illustrating the effects of aspirin on the risk of bowel cancer in people aged 50 to 70 years. They also used the expected tree structure to explain the use of drugs called selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) in women at increased risk of bad cancer.

The team examined the clinical implications of Australia's new guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of bowel cancer, including the prescription of drugs that reduce the risk of bowel cancer.

The guidelines were published by the National Council of Medical Research and Health in 2017 and were led by the Cancer Council Australia with the contribution of Professor Jon Emery of the University of Melbourne.

Studies have shown that taking aspirin for as little as two and a half years can reduce the incidence of bowel cancer, people at increased risk of bowel cancer being able to benefit more than those at average risk of bowel cancer.

Overall, studies have shown that benefits such as reducing the risk of heart attack and reducing bowel cancer far outweigh the potential harms of using alcohol. aspirin, such as gastrointestinal bleeding.

Target ovarian cancer

Read more

It is estimated that for a person aged 50, taking aspirin for 10 years is 10 times more likely to prevent death than causing it, and five times more for a 65-year-old.

For the study, professors Jon Emery, Jennifer Walker, Jesse Minshall, Kara-Lynne Cummings, and Peter Nguyen developed new risk communication methods, including "expected frequency trees," to demonstrate this. that it would happen to 10,000 men and women in Australia aged 50 to 70 years if they took aspirin.

The diagrams – which have a trunk and branches – show the likely results after 10 years of taking aspirin for at least five years. These visual summaries aim to present the probability of specific outcomes to help patients make more informed decisions about treatment.

Peter Nguyen, a Ph.D. candidate in the Cancer in Primary Care group at the University of Melbourne, conducted a study of general medical patients to evaluate risk communication methods, including 39; frequency tree planned, for the use of aspirin as a specialized student last year. He emphasized the importance of involving patients in the treatment selection process.

"There is a shift in the encouragement of shared decision making, showing patients the pros and cons of knowing they want to take drugs for cancer prevention," said Nguyen. .

"This research clearly shows that the benefits of taking aspirin for the prevention of bowel cancer always outweigh the possible adverse effects of the cohort of patients aged 50 to 70 years, even over long periods. "

Our cancer prevention genes have been revealed

Read more

For the prevention of bad cancer, several randomized controlled trials have shown that drugs such as tamoxifen and raloxifene (called SERM) significantly reduce the risk of bad cancer in women who do not have bad cancer. 39, personal antecedent.

The data badysis of nine prevention trials showed a bad cancer incidence reduced by 38%. Participants included women at increased risk of bad cancer as well as women at medium risk, as well as premenopausal and postmenopausal women. The Australian guidelines recommend that women at increased risk of bad cancer, because of their family history, consider the use of SERM to prevent bad cancer.

The expected frequency trees are intended to clearly indicate the benefits and side effects of taking three different SERMs for bad cancer chemoprevention.

Trees show that the decision to take a SERM is potentially more complex than for aspirin. Women with a family history of bad cancer who wish to explore SERM for chemoprevention may be better directed to a family cancer clinic or specialized bad cancer service. The discussion about taking aspirin for the prevention of bowel cancer may well fit into primary care.

The guidelines for aspirin and SERM reflect a new approach to cancer prevention in primary care.

The decision to prescribe these medications involves a thorough discussion with a patient about the potential benefits and harms and taking into account the underlying disease risks. Decision trees can be important and effective tools for guiding and informing vital discussions about prevention with patients.

Banner: Shutterstock

Source link